Deeply fragmented, plagued by low profit margins and facing a rapidly shrinking workforce, the UK construction sector faces an ominous future.

Demand for its services is rising, and if the top 20 contractors do not consolidate and become the top five, for instance, much bigger and better-capitalised firms from outside, particularly from China, seem certain to sweep in and do the job for them.

The stark premise is this: rich, developed countries can lose the ability to build for themselves.

For evidence, look at Israel. Faced with manpower shortages and a lack of basic capacity, its government last year asked five big Chinese construction companies, and one Portuguese one, to come and build homes. Each would be allowed to bring up to 1,000 of its own workers, and each would have to show it had started building at least 250,000 square metres of new housing by the fourth year.

Israel may be the start of a trend which the UK seems set to follow.

Its construction sector is under pressure from all sides. Experienced workers, managers and professionals are ageing en masse and are not being replaced. This profound manpower depletion could be exacerbated by Brexit. The sector’s capacity is hobbled by chronic structural vulnerabilities: it is fragmented and reluctant to embrace innovation; it is prone to waste and error; and it scrapes along with tiny, or vanishing, profit margins.

Seemingly unable to rouse itself, the sector is heading for the rapids of sharply increased demand, in housing and in the government’s bulging infrastructure pipeline, which includes very big items like new nuclear power stations and the high-speed rail network, HS2.

Put together, it equates to a vice that is tightening inexorably, and something will have to give. The national crisis now unfolding over residential tower-block fire safety only adds to the feeling of sectoral unsustainability.

This time we mean it

The language used in recent years to describe the gathering skills shortage in the UK has tended toward the dramatic. “Skills time bomb”, said the Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) in 2013. “Severe and immediate shortages”, warned KPMG and the London Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 2014. “Perfect storm”, said Zurich, the insurance company, in 2015. As 2016 drew to a close Mark Farmer, author of the latest of many reviews on the industry, reached for the starkest injunction yet – “Modernise or die”.

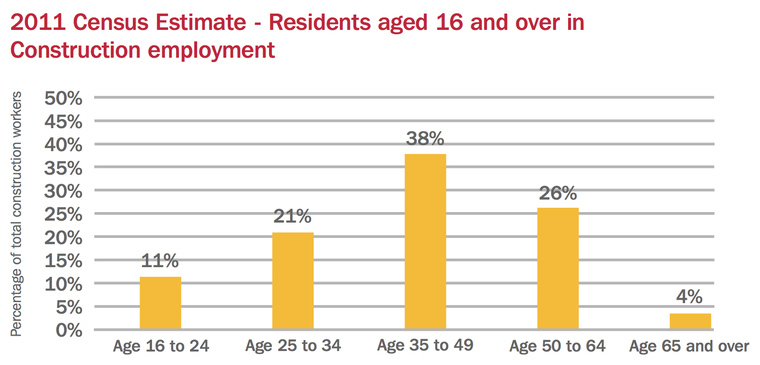

The language may have de-sensitised the industry. If true, this is unfortunate because the numbers are indeed alarming. Put simply, the UK construction industry is losing workers faster than it is recruiting new ones. The most widely cited set of “smoking statistics” comes from a 2011 census which found that 30% of the total construction workforce (totalling about 2.1 million) were over the age of 50. The youngest of these are now 56. This cohort of up to 700,000 will be packing their things and heading for the exit before the decade is out. Close on their heels will be an even bigger group, the 38% (around 800,000) who were between the ages of 39 and 45 in 2011 (now aged 45 to 51). It means the hall is emptying quickly, and the rate at which it is emptying will speed up, and stay sped up.

(Farmer Review/ONS)

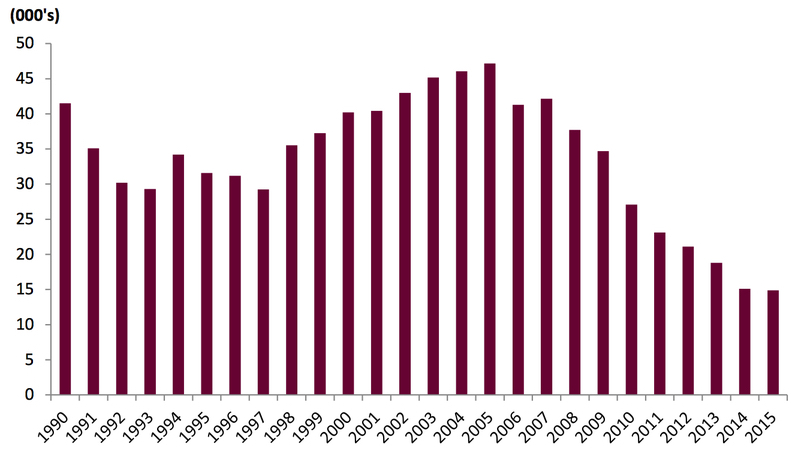

Meanwhile, young people are not racing in to fill the hall behind them. According to the CITB, in 2015 the number of first-year trainees among all construction occupations stood at just 14,900. That number is the latest point on a steep and relentless decline from 2005, when the number exceeded 45,000. (See Figure below) Farmer has warned, “we could see a 20-25% decline in the available labour force within a decade”.

Numbers of first-year trainees 1990-2015 for all occupations in Great Britain (CITB)

Rising demand

This demographic trend is occurring at a time when demand for construction workers and professionals is set to rise. One driving factor is housing. Like in Israel, supply in the UK has failed to match demand for decades.

Newly awakened to the issue, government is exerting pressure, and home construction is on the rise. In England, official figures show that 170,690 homes were added to the national stock in 2014-15, a 25% increase on the previous year. The rise continued last year, with 189,650 net additional dwellings in 2015-16, up 11% on the year before.

Infrastructure is another driver of demand. In 2015 the government released its National Infrastructure Pipeline, a schedule of projects together worth £411 billion (in 2013-14 money) in sectors including energy, transport, waste, flood defence, and communications. Included were megaprojects such as HS2, Hinkley Point C nuclear power station, the Thames Tideway Tunnel (known colloquially as the “super sewer”).

The government said delivering these would require an extra 100,000 workers, who would need to be recruited and trained by 2020.

The skills challenge did not stop there, however. In the government’s analysis, because of the changing “skills blend” needed to deliver the plans, around 250,000 of the existing workforce would need to be retrained over the next decade, in addition to the extra 100,000 workers. In December 2016 the government added 20 more projects to the pipeline which, along with other inclusions, pushed its combined value to more than £500 billion.

So at a time when the UK construction workforce needs to be expanding and “up-skilling”, it is shrinking. And after the Brexit vote on June 23, 2016, there is widespread concern is that the workforce will shrink even more.

The Brexit effect: Time to panic?

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) assessed the size of the migrant construction workforce in 2016 and came up with a figure of approximately 126,000 EU workers. Viewed against the industry’s underlying skills problem, with an exodus of 700,000 looming in the next decade, to be followed by 800,000 more, this might be classed as “a headache we could do without” rather than a catastrophe.

It doesn’t really matter about the exact scale of the problem. The question is whether it’s big, very big, or enormous– James Bryce, Arcadis

But companies operating in London will be hit hardest, because the data suggest that EU workers are concentrated heavily in the capital.

In the days before the referendum architect Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners said Brexit would be a “catastrophic error of judgement” and that more than 40% of its staff were non-British EU citizens.

Britain’s biggest contractor, Balfour Beatty, worries that it may no longer be able to handpick highly skilled engineers from EU countries.

Structural weaknesses

Even if the industry retained access to a plentiful and versatile source of labour and skills from Europe, it would still be in trouble.

“It doesn’t really matter about the exact scale of the problem. We know it’s big,” James Bryce, director of strategic workforce planning at Arcadis, told us. “The question is whether it’s big, very big, or enormous, and what are we going to do about it?”

The reasons for the skills crisis and for UK construction’s chronically poor productivity go back decades.

There is the deep fragmentation of the industry into long subcontracting chains in which main contractors win the work, then pass the cost of training down the line to the companies who can least afford to bear it. If you were to depict the shape of the industry according to company size, it would be like a very young tadpole, with contractors whose name you might recognise clustered in the plump little head, and everyone else stretched out along an absurdly long tail.

The latest survey by the CITB shows that 86% of firms employ fewer than 10 staff whereas only 1% employ 100 or more.

You do not have to travel far along the tadpole’s attenuated tail before its thickness reduces to the width of a single cell, because around 40% of the overall labour force is thought to be self-employed.

Powerful incentives drove this mass casualisation. Often abetted by payroll companies, contractors effected the wholesale transformations of permanent staff into freelancers, allowing the companies both to protect themselves against economic downturns and to slough off the costly burden of holiday entitlements, sick pay, employer’s National Insurance contributions and company pensions – not to mention the responsibility to train.

As a result, the NIESR says roughly a third of British construction workers are not qualified even to NVQ level 2, and fewer than half have completed an apprenticeship. “The figures for trainees and apprentices are a disaster,” says Linda Clarke, professor of European industrial relations at Westminster University. “There’s a lot of low-level training, but it’s NVQ2 if you’re lucky.” She adds that only 16% of all construction trainees are pursuing an NVQ level 3, which is the standard level in much of mainland Europe.

Just about managing

UK construction is less an “industry” than a vast expanse of territory comprising hundreds of thousands of companies (234,000 of them classed as contractors), finely minced in terms of function and geography, all chasing work, on price, from an equally vast and variegated universe of clients. Analysis carried out for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills in 2013 showed that for a “typical” large building project, that is, in the £20-£25 million range, the main contractor may be directly managing around 70 subcontracts of which a large proportion are £50,000 or less.

Driving innovation into this territory is difficult.

Meanwhile, up in tadpole’s head, the UK’s biggest contractors are hurting.

These are the ones who should be in a position to respond to the gathering demand for large programmes of infrastructure and residential building. But among the top 20, five made a loss in 2014-15. Loss-makers include the UK’s biggest contractor, Balfour Beatty, whose turnover of £8.4 billion is around double that of its nearest rival.

Even Laing O’Rourke, which is doing everything the industry is supposed to do – investing heavily in its pre-manufacturing capability and returning to a directly employed labour model – reported a £141 million loss for its UK construction business for 2016. Farther down the tail, the average profit margin among the top 50 contractors in the UK was just 1.05% in the same period.

It can take a decade, from starting an apprenticeship, for someone to gain all the skills they need, says Balfour Beatty (Balfour Beatty)

There are some bright spots in the form of companies that are prepared to invest in the quality of their processes and people in order to build future capacity. But they need the price they negotiate for contracts to pay for this investment and, for every one of them, there are others content to defer such investment and bid low to harvest turnover, gambling quarter by quarter that somehow everything will come right in the end.

An ever-fresh supply of inexperienced clients keeps such companies ticking over, which exerts downward pressure on contract prices.

Last year professional services firm EY (formerly Ernst & Young) warned clients to guard against the financial and reputational risks of projects going wrong by constantly monitoring contractors for tell-tale signs of impending failure, including sudden departures of top executives, over-stretching into non-core areas, disputes, poor risk and commercial management.

The sector is over-ripe for consolidation, EY concluded.

Enter the dragon

Meanwhile, the UK government has actively encouraged Chinese participation in financing and delivering infrastructure. In 2013, then-chancellor George Osborne said the UK would open the door for Chinese companies to take a stake, eventually even a controlling stake, in British nuclear power plants.

In 2015 George Osborne also sought Chinese participation in UK high-speed rail, specifically urging Chinese firms to join UK firms in bidding for seven contracts, together worth £11.8 billion, comprising the first phase of HS2.

China’s track record in building high-speed rail is as impressive as its civil nuclear prowess. If a country needs big, complex and expensive things built quickly, China is the genie in the lamp.

Sir John Armitt, former head of the Olympic Delivery Authority, spotted the potential in 2014, telling us that the influx of Chinese cash and capability could be an answer to the chronic weakness of the UK’s contracting sector.

“Major British companies in the construction industry are fundamentally undercapitalised,” he said, referring to the profit warnings Balfour Beatty had begun issuing. “It’s ridiculous that the largest construction company in this country, faced by a £75 million drop in profits, goes into meltdown. What you’re seeing across the field at the moment is the penetration of the UK market by Continental contractors and I see no reason why that shouldn’t be followed up by Chinese companies.”

One company to watch is state-owned China State Construction Engineering Corporation, claimed to be the biggest construction company in the world. With revenue of $140bn (£109bn) in 2016, it dwarfs Britain’s biggest builders.

Too late?

You can find people, but not necessarily great people

This year the UK industry, government and the sector training body, the Construction Industry Training Board are wrangling over how to fix the training regime. But it is hard to see how industry can respond in time.

Even if the industry managed to recruit 100,000 new people by 2020, Balfour Beatty makes the obvious point that it can take a decade, from starting an apprenticeship, for someone to gain all the skills they need.

The skills crisis is not just looming, it is already here. Even large, well-resourced, multinational consultants are struggling to find talent. The head of staff development at one of these told us that it was now paying staff to recommend friends and family.

“You can find people, but not necessarily great people,” the executive said. “Winning work in a joint venture with other organisations – it’s like an arms race. We are fishing in the same talent pool, and you get wage inflation, higher attrition, higher turnover, lack of continuity, and loss of confidence.”

Worryingly, the rarest breed are the technical stalwarts of the industry, such as clerks of works, chartered surveyors and building surveyors, especially in the regions where large projects suck up resource, the executive added.

Ominous possibilities

As pressure builds, a number of things might happen. It may catalyse an unprecedented slew of mergers and acquisitions in which, say, the UK’s top 20 contractors become the top five. Such sweeping consolidation could create a new environment whereby each super-sized company was finally able to marshal resources for the necessary step change in process innovation, and in which, collectively, they are able to alter the rules of the contracting game so that increased productivity is rewarded by the market.

Another possibility is that Chinese companies swoop in to buy British ones. This happened in Australia when contractor John Holland, a household name in the country, was acquired by a subsidiary of the state-owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), the fourth largest contractor in the world, in 2015.

Chinese contractors have for years been eager to break into Western markets, and in the UK acquisitions may provide the avenue – one currently paved by a substantial discount on the pound.

These two scenarios seem almost certain to unfold in the UK, and soon. But neither solves the country’s capacity crunch.

Sweeping consolidation would itself be disruptive as merged companies can take years to bed in; and acquired firms, however rejuvenated and recapitalised, would still face the limitations of the UK’s shrinking and under-skilled labour force.

For this reason the contours of a third scenario – Israel’s – emerge on the horizon: that of large Chinese companies successfully bidding for the biggest infrastructure contracts and bringing their own people to do the work. Politically, this could be difficult, but the political case could be made that speedy delivery of critical infrastructure warrants unusual measures.

For UK companies, being sidelined in this way would be damaging. They would be cut off both from significant revenues and opportunities to develop capacity. The public, however, may grow accustomed to seeing Chinese labour camps on the periphery of major construction sites.

In that scenario, an apt title for the next government-commissioned report on the industry would be: “We Told You It Was Serious”.

- A longer, fully cited version of this essay appears in the April edition of Construction Research & Innovation. GCR readers can access it free here.

Top image: Safety briefing at a construction site in China (RudolfSimon/Creative Commons)

Comments

Comments are closed.

You are right. Our labour force is diminishing and the skills are getting less. Every contract we start seems to be a bigger battle to find suitable skills to carry out the work. We have to work harder to keep our sub contractors on board for the next contract in the fear of not finding anyone else to do the work.

As for a career choice. Contracted for a 50 hr week, working every weekend, no pension provision, more liable than ever to carry the liability for someone else’s mistakes, I have told my children who are in the process of choosing careers to avoid construction. The love of creating structures is loosing its allure the older I get as I realise that as a construction worker I and my colleagues are bottom of the pile, with little job security. Let the Chinese in, things can only get better.

shortage of people to do the work competently – yes

shortage of ‘expert commentators’ – no

is that another facet of feckless britain?

We must train up our own young people

apprenticeships are a good idea

engineering and fringe businesses are exciting to work for

as indeed is manufacturing and assembling components

but we do not want foreign countries controlling our industries

and those who come must work to our standards & especially H S E

And we want them here on visas

I did it working with a visa in the middle east

tryst this helps

Mark Benson

B Eng

Bringing the Chinese is a stop gap solution. Operating in Kenya we see how local companies are pushed out of the market and local capacity (quantitatively, but even more qualitatively) is slow to develop. In addition the practices of many Chinese companies, requiring materials, equipment and manpower to be sourced from the home country and imported often flouting import regulations, taxes and duties (nothing illegal, as all this is negotiated beforehand) has a damaging effect on the local economy.

This being said, we acknowledge the technical capacity of many Chinese companies, it’s the way they operate (we have the gold and we set the rules) that should make any government think hard before they bring in hard to control powerhouses.

The key question here is will the UK have the capacity to build to meet our requirements? The statistics presented in this paper, which are not new and well recognised, when pulled together, as Rod has done so ably, lead to an almost editable conclusion that we will not. In the UK this is compounded by 25% of our stock being pre-1919 and requiring labour intensive maintenance and refurbishment. Even off-site manufacturing will do little in the short-term to reduce the labour which is absorbed into our heritage stock. If we want major projects to be carried out efficiently and quickly where will we go for the labour. The industry could potentially become dysfunctional. We should watch with interest what the Israelis are doing.

There is much more to this. As soon as the Chinese get a foothold specifications will be re-written to accommodate Chinese manufactured goods, new consultants will appear with UK liaison consultants acting as go-betweens for government and local government and before long the UK will be just another shell market with little construction manufacturing or expertise.

Remember, the Chinese don’t need to worry about profit or shareholders. They do what is right for them in the long term, no matter how long that may be.

It happened with the Japanese with cars, electronics and cameras and will happen with construction.

Anyone for Mandarin classes?

@David Mccormick. So what is is answer if we have insufficient of our own personnel to meet demand, as Rod Sweet suggests could be a possibility?

In response to Michael Brown:

I do not have all of the answers – in fact I probably have none but here goes …

1 – do we need highly skilled individuals to undertake the majority of ‘construction’ tasks? Probably not. We require able individuals who are prepared to undertake fairly simple but arduous tasks often in poor weather and often in hazardous situations. These people would not require 5 year apprenticeships to become proficient but they would need to understand the H&S aspects of working on Site and also the dangers of using sometimes dangerous tools. Examples would be formwork joiners, reinforcement placing, concrete placing, plant operators etc.

2 – greater use of pre-fabrication where practicable, whether on Site or off Site

3 – re-introduction of the Property Services Agency (PSA) or something similar to provide a robust base line of specification. This should be mandated on all ‘government’ work

4 – reduction in the use of ‘commercial teams’ whose role appears to be making money for themselves rather than quickly resolving ‘disputes’ (often exacerbated by the very teams introduced to resolve the issue!)

5 – introduction incentive schemes in construction (I know, they exist in NEC3 Option C) – but why don’t we hear more about the successful projects?

I could go on but that would be boring.

Everyone’s concern is related to the relatively short times allocated to the execution of the works, to the qualification of the workers and others, but we all forget the theoretical and practical training of both the youth involved in the construction activity and the existing / stable personnel in construction companies.