True to his word, Chinese businessman Wang Jing showed up in Nicaragua on 22 December to mark the start of construction on the canal that will link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and give the Western Hemisphere’s second poorest country an economic turbo charge – or so its promoters promise.

But the event was marred by violence as police broke up protests led by those living along the 276-km canal route who fear their land will be taken without adequate compensation.

And questions were raised again about how exactly the gigantic scheme, which the Nicaraguan government assumes will cost no less than $40bn, would be funded. Observers have concluded that it will be bankrolled by the Chinese state.

Approximately 400,000 hectares of rainforest and wetland will be destroyed– Nature journal

Scientists and environmental groups have also made fresh demands for a transparent environmental impact assessment. Chief among their concerns is a plan to dredge a deep channel through Lake Nicaragua (Cocibolca), Central America’s largest lake. They worry this will cause an environmental disaster.

Arrests

Anyone hoping to see excavators getting stuck in to the vast ditch on 22 December will have been disappointed.

What broke ground that day was not the grand canal, a century-old dream for some Nicaraguans, but rather the start of renovations to an access road to a proposed to port and set of locks near Rivas, at the western shore of Lake Nicaragua.

The cautious start didn’t dampen the hyperbole of Wang Jing, owner of Hong-Kong-based company HKND, which, in June 2013, got vast powers to expropriate land to build and operate the canal.

“The Grand Canal of Nicaragua will be a great contribution to their [sic] wealth of Nicaragua people and to the development of the humanity,” he told the hand-picked audience of Nicaraguan officials and cheering HKND employees in the capital, Managua, later that day (pictured).

He also vowed that the Chinese companies building the canal would respect the rights of the Nicaraguan people. “Without the consent of the owners, or the satisfaction with the compensation, not a single plant on their land will be touched,” he said, according to the text of his speech on HKND’s website.

Angry “campesinos”, subsistence farmers whose homes and land lie along the canal’s proposed route, were not reassured. They have been complaining of Chinese surveyors turning up under the protection of Nicaraguan soldiers, taking measurements, and leaving without a word. They say they have had no information yet about compensation even though construction has now started.

While Wang was giving his speech, protestors in Rivas blocked the Pan-American Highway. Another group blocked the Managua-San Carlos Highway.

On the evening of 23 December riot police moved in on the barricade at Rivas where 40 were arrested, according to the Nicaraguan daily newspaper La Prensa. The second roadblock was cleared with force on the following day, Christmas Eve.

Six protest leaders were held without charge for six days, contrary to Nicaraguan law. Among those released on 30 December was Octavio Ortega, president of the Fundemur NGO (no relation to Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega), who claims that he was badly beaten while in custody.Â

Disaster

Opposition to the canal based on environmental concerns has been growing as well.

In February 2014, Jorge A. Huete-Pérez, a molecular biologist and president of the Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences, along with German zoology professor Axel Meyer, wrote an article in the journal, Nature, warning that the canal could create an “environmental disaster in Nicaragua and beyond”.

Dredging a 90-km swathe of Lake Nicaragua to the required depth of more than 27m (from the current average depth of 15m) would release millions of tonnes of damaging sedimentation, they said, adding that salt infiltration from the coastal locks would damage the freshwater ecosystem. The introduction of invasive foreign species from container bilge water was another of their concerns.

Approximately 400,000 hectares of rainforest and wetland will be destroyed, they claimed.

They called on international conservationists, scientists and sociologists to join Nicaraguans in demanding an independent assessment of the canal’s repercussions.

HKND hired UK-based Environmental Resource Management (ERM) to assess the environmental impact, but scientists, unhappy with the secrecy surrounding the process, have assembled an ad hoc review process of their own.

In his speech, Wang Jing said the final environmental impact assessment would be delivered in April 2015, though he did not say to whom. In their article, Huete-Pérez and Meyer worried that HKND is under no obligation to make the report public, and called on President Ortega to halt the project if a truly independent assessment confirmed their fears.Â

‘All Nicaraguans should know’

HKND’s immunity from due environmental process in Nicaragua is just one example of how President Ortega has surrendered a big chunk of the country’s sovereignty to an unknown Chinese businessman, says a campaigning young Nicaraguan lawyer named Monica Lopez Baltodano.

On 13 June 2013, without any prior public consultation or debate, the Nicaraguan national assembly approved Law 840, granting the interoceanic canal concession to HKND for 50 years and an optional further 50. The agreement and the law that backs it up conferred astonishing powers to the Chinese company, including the right to expropriate any land it deemed necessary for the project.

Law 840 provoked anger among Nicaraguans.

Octavio Ortega, president of the Fundemur NGO, claims he was badly beaten (Facebook)

In August 2013, 183 citizens presented 31 suits of unconstitutionality to Nicaragua’s Supreme Court. One of those suits, specifically against Daniel Ortega, was presented by Baltodano, who claimed to find violations of more than 40 articles of the Nicaraguan constitution.

But in a single day, on 18 December 2013, the Court dismissed all 31 suits out of hand.

Baltodano then published a document called ’25 truths on the canal concession’, which, she says, “all Nicaraguan citizens should know”.Â

She compiled the “truths” after analysing Law 840 and the 120-page concession agreement.

The latter, she argues, is wrongly given the status of law because it is so enmeshed with Law 840.Â

She notes that it also obliges a constitutional reform to be made within 18 months to legalise its own provisions, with the aim, she said, “of adjusting our Magna Charta to big capital’s corporate interests”.

On the environment, she writes: “The concession was approved without any prefeasibility or environmental impact studies having been done, leaving it to the concession holder’s discretion under what parameters to conduct them, thus ignoring the environmental legislation, the environmental permits regime and the most basic common sense.”

She argues that “potentially the whole national territory has been handed over through the concession as no specific routes or locations are defined for any of the ten sub-projects associated with the canal included in the concession”. (As well as the canal, HKND intends to build two ports, a number of tourist resorts, an international airport, a power station, and cement and steel factories, a railway and a pipeline.)

“All use rights of the land, air, water, maritime spaces and natural resources,” Baltodano adds, “have been handed over, without valuing the importance of environmental integrity to guaranteeing the life of Nicaraguans”.

And Nicaragua gets very little in exchange for handing so much to HKND, Baltodano claims.Â

The canal and related infrastructure will be 99% owned by HKND from year one, with ownership transferring to Nicaragua at a glacial rate of 10% every decade.

That means the cash-starved state, whose poverty is surpassed only by Haiti in the Western Hemisphere, can look forward to getting full canal revenues only after a century.

In the meantime, HKND will pay the government just $10m per year.Â

“But,” writes Baltadano, “the Agreement literally states that they could pay us between $1 and $10 million. The investor can deduct from the amount any current and even future debts it deems it is owed.”

“The national budget will not receive a single córdoba in the form of taxes or duties for any of the works,” she adds.Â

When will it make money?

Questions are also being asked about the viability of the canal as a business. Arguments for it rest on the assumption that ever more and bigger ships will ply the high seas.Â

Currently, the Panama Canal can handle ships loaded with up to 5,000 containers, or “TEUs” (twenty-foot equivalent units). These so-called “Panamax” ships are now dwarfed by “Post Panamax” ships, able to carry up to 13,000 TEUs.Â

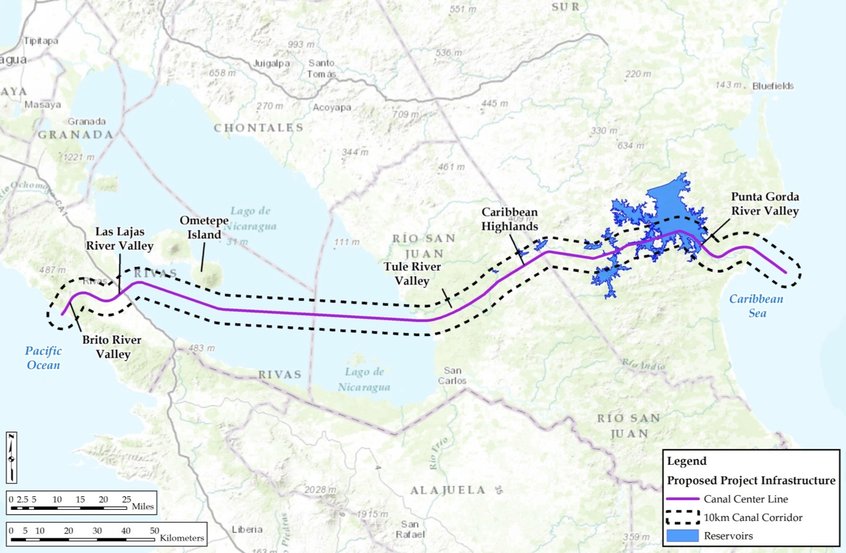

Proposed route of the canal stretching 275.5km from Caribbean to the Pacific, with around 90km traversing Lake Nicaragua (source: HKND)

In 2006 Panama hatched a $5.3bn plan to expand the canal and build a new set of locks to accommodate these giants. The plan was approved by a national referendum and work started in 2007, with completion expected in 2016.Â

But according to promoters of the Nicaragua Canal, this expansion will already have missed the boat because ships just keep getting bigger. HKND says the Nicaragua Canal will be able to accommodate “Super Post Panamax” ships up to about 25,000TEU.

HKND, advised by consulting firm McKinsey, is working on the assumption that global maritime trade will grow in volume by around 4% a year, causing traffic jams at the Panama and Suez canals, even though both are now undergoing major expansions.

But does the business case hold water? Down in Panama, the canal generated $2.4bn in 2013, and just under a billion of that – what you might call the canal’s “profit” – went to the Panamanian Treasury. (The Panama Canal Authority publishes its financial information here).

If the canal costs $40bn, it will be an investment four times the size of the entire Nicaraguan economy–

Assuming that the Nicaragua Canal immediately captures as much business as its southern competitor, and assuming it, too, can clear a billion dollars every year, it will take several decades for the $40bn canal to pay for itself, even accounting for growth in global shipping. (This also assumes $40bn is accurate and not a wild underestimate, as is very nearly always the case with huge, state-promoted infrastructure projects.)Â

It’s a crude calculation, but it may help illustrate the enormity of building such a major piece of infrastructure from scratch.

Nor is it clear how the canal’s punishing construction schedule will affect costs. HKND insists vessels will be navigating the channel in just five years, which is an extremely compressed time frame given that Panama is taking nine years merely to expand a canal that is just a third the length of Nicaragua’s.Â

And who’s paying?

Observers are mystified as to where the $40bn will come from. In October 2013 Wang told the South China Morning Post that “talks with international investors have been very smooth”. He said some were already on board and that he would reveal all that December.Â

He didn’t, and a year later, we’re still in the dark. There have been reports that HKND has so far secured only $200m in funding commitments – a drop in the $40bn bucket.Â

After his speech last month Wang surprised reporters by saying that HKND would raise funds through an initial public offering (IPO), though he didn’t say when or in what stock market.

Naturally, some have concluded that the only entity capable of funding and executing such a vast, speculative, and lightening-speed mega-project is the Chinese state itself.

“If the canal goes ahead … it will be because the Chinese government wants it to, and the financing will come from China’s various state firms,” said Arturo Cruz, professor at Nicaragua’s INCAE business school and a former Nicaraguan ambassador to the United States, in an interview with Reuters.Â

Infrastructure diplomacy

The canal certainly complements the Chinese government’s official strategy of opening up a new, global “Maritime Silk Road” to accelerate the flow of goods to and from China.

It could shave 10 or more days off the journey from America’s east coast, canal proponents say. Super-tankers carrying oil from the Gulf of Mexico, Brazil and Venezuela, and iron ore from Ontario and Quebec, could make 12 trips a year instead of nine, and save up to $2m each round trip. The canal would also let China ship its manufactured goods much more quickly to the densely populated eastern coasts of both North and South America.

Wang Jing, however, insists that HKND is just a private company pursuing a project in Nicaragua, and categorically denies that the Chinese government has any involvement in the scheme. He has even pointed out that China and Nicaragua have no official diplomatic relations.

This is true, and stems from the fact that Nicaragua is one of only 23 countries holding out in recognising Taiwan, a sore point for China. So while Chinese President Xi Jinping can happily sit down with Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff and Peruvian president Ollanta Humala to push for a South American transcontinental high-speed rail scheme, he cannot be seen shaking hands with Daniel Ortega.

Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega speaks during the groundbreaking ceremony, 22 Dember 2014 (source: HKND)

Nevertheless, Wang was certainly singing from the official Chinese hymn sheet when, in his speech on 22 December, he waxed lyrical about China’s 2,100-year-old Silk Road credentials, and enjoined his audience: “let us bless and create immortal glory for the Maritime Silk Road of the 21st century, which will carry the dream and happiness of future generations and promote in Nicaragua profounder integration and prosperity of East and West”.

A reasonable prediction may be that Nicaragua switches recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic this year, making official Chinese involvement through state-owned banks and construction firms possible – and the canal scheme itself, at last, comprehensible.Â

Trusting Ortega

Whoever its funders turn out to be, the Grand Canal scheme shows all the signs of going ahead. On groundbreaking day Wang Jing set out the timetable for 2015. In the first quarter surveying, design, land acquisition and access road construction would proceed, he said.Â

The environmental impact studies would be delivered at the end of the first quarter. In the third quarter, bidding for the job of excavating a section between Tule and La Union would take place, and work on that section will begin. In the fourth quarter tendering will take place for the design and construction of the east and west locks.

The high-handedness and secrecy characterising the project so far makes ammunition against it easy to assemble. Ecological concerns especially will be amplified outside Nicaragua in the developed world, where the environmental destruction underpinning its wealth happened long ago.

On the other hand, most Nicaraguans welcome the canal, and trust Daniel Ortega when he says it’s a good thing. An estimated 30,000 people will be affected by the canal route, but HKND claims that building it will create 50,000 jobs in a country of 6 million, of whom 42% live below the poverty line.Â

(A detailed project description released last month said that up to half the 50,000 construction jobs would go to Nicaraguans, but that the country’s limited skills base meant that the rest of the positions would be filled one quarter by Chinese workers and one quarter by workers from other countries.)

New special economic zones at either end plus the resorts and other related developments could stimulate and diversify an economy overly dependent on commodity agriculture and vulnerable to scourges such as the coffee rust fungus.

For many, the canal is an obvious way to make Nicaragua like Panama, which has a developed, services-based economy and where per capita GDP is four times higher. Others point out that what damages the environment most is poverty, which fuels illegal logging and clear-cutting for agriculture that destroys an estimated 70,000 hectares of rainforest per year.

In 2016 Ortega, leader of the socialist Sandinista National Liberation Front party (FSLN), faces a general election. He can seek a third term as president of the republic thanks to a change in the constitution scrapping the two-term limit, a change he asked for and which the elected National Assembly granted in January last year.Â

If the canal costs $40bn, it will be an investment four times the size of the entire Nicaraguan economy, so the 2016 election is sure to be fought over little else.Â

Ortega’s FSLN is revered by many Nicaraguans. It led the revolution that toppled the four-decade-long Somoza dictatorship in 1979, and fought a dirty war against the CIA-backed Contras for much of the 1980s. But fears are growing over a creeping authoritarianism on the part of Ortega, now cast by some as an aspiring “eternal president” controlled by Chinese interests.

This year there is much he could do to defuse these fears. He could start by requiring HKND to be clear about what’s on the table for Nicaraguans who face evictions, and by being ready to stand up the best possible deal on their behalf.

He could demand that the environmental study be fully transparent, and acknowledge that you cannot dig a 280-metre-wide trench across the country or dredge Central America’s largest freshwater reservoir with minimal impact. Nicaraguans deserve to know what they’re letting themselves in for.

At the same time he could listen to concerns over the surrender of Nicaraguan sovereignty to an unaccountable Chinese entity, and be prepared to negotiate terms that protect the rights and interests of Nicaraguans in perpetuity.

Comments

Comments are closed.

It is a challenging project!

On the Mexican side of the border the tunnel entrance went down more

than 80 feet to a wood lined floor and on the U. This is the

main reason why vehicles auctioned by the Federal Surplus Vehicle Auctions are still in its

optimum performance when they are sent to auctions.

This is one of many reasons President Barack Obama is offering $10,000

in scholarship aid to women and mothers to better their

education.