At the beginning of September, a blueprint for delivering a new generation of “garden cities” in the UK won the Wolfson Economics Prize.

It may not be widely known outside the UK but the prize did net its winner, the urban planner David Rudlin, of the consultancy URBED, just over $408,000 (£250,000), which makes it the second most lucrative economics prize after the Nobel.

More than that, the award reignited debate in the UK over how to tackle the country’s chronic housing shortage, with old battle lines hardening around whether or not to build on green belts.

Originally intended to prevent unsightly urban sprawl, green belts around English cities and towns have been blamed for blocking development and keeping house prices artificially high while protecting under-used agricultural land that has low ecological value.

And with around 65% of people in England and Wales owning their own home – and benefitting from rising house prices – successive governments have avoided changing the status quo.

Meanwhile, the supply of homes continues to lag behind demand. Current demographic and population forecasts indicate that 240,000 new homes are needed every year up to 2031, while fewer than 140,000 were completed in 2013.

Into this impasse came David Rudlin with his plan for Uxcester, an imaginary small city that he believes encapsulates the characteristics of dozens of others in the UK which could be doubled in size by taking a “confident bite” out of its green belt.

Last year the wealthy Lord Wolfson (first name Simon), a Conservative Party peer and chief executive of clothing retail giant Next, launched his second Wolfson Economics Prize by posing the question: “How would you deliver a new Garden City which is visionary, economically viable, and popular?”

On 4 September judges chose the Uxcester scheme (it’s pronounced “USS-ter”), with Wolfson calling it a “tour de force of economic and financial analysis, creative thinking and bold, daring ideas”. Why did they like it so much?

Today’s proposal from Lord Wolfson’s competition is not government policy and will not be taken up– Brandon Lewis, UK housing minister

Rudlin tried to imagine how to avoid the acrimonious battles that erupt when permission is sought for new out-of-town developments and how, instead, to arrange it so that cities competed for new housing on their outskirts as fiercely as they might bid for the Olympics.

He tackled how the extensions could feel as if they’d grown up organically instead of being soulless, isolated, dormitory suburbs stamped by a giant cookie-cutter onto the green belt.

And he proposed a financial model that might allow the city extensions to pay for their own infrastructure, and return dividends to investors, as they grew.

“We seem entirely unable to build a new settlement that comes even close to the richness, diversity and character of an ordinary English market town,” Rudlin writes in his submission.Â

“In the face of this failure our response has tended to be that it is probably better not to build than to build badly. Local people – branded as NIMBYs – have come to see new housing as a threat and the planning system has become fraught with conflict. The result is that we are building half the homes that we need.”Â

New social contract

Concluding that it is “probably impossible” to create a garden city of any scale from scratch, Rudlin decided that a better approach would be to graft a garden city onto the “strong root-stock” of an existing city, nearly doubling its size. But how would the NIMBYs of Uxcester ever go for that?

Central to Rudlin’s proposition is a ‘social contract’ with the people of Uxcester, which sets up a win-win scenario for everyone. Its clauses could include:

- For every acre of green belt developed, another will become public open space. This is interesting because, as is the case with many small cities, the green belt around Uxcester is farmland that is neither accessible to the public nor has it much of what Rudlin terms “ecological value”. So for every hectare set aside for buildings and roads, another is given back to the city as public space, forests, lakes and country parks.

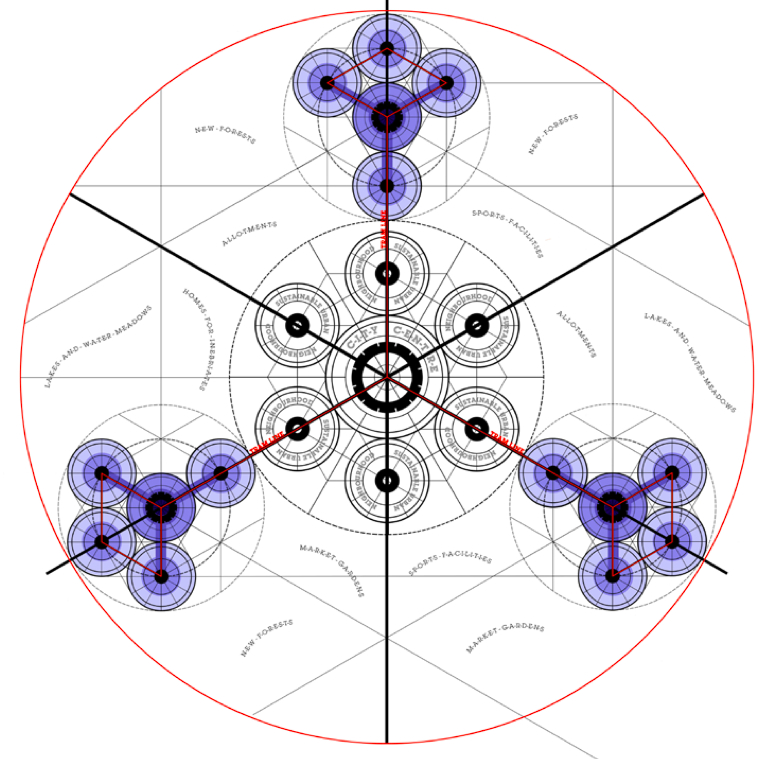

- The new developments won’t wreck the established setting of the city. Three triangular developments will ease their thinnest angle into the centre just enough to make the necessary infrastructure links, while the green views of edge-of-town residents will be preserved.

- They will have great public transport infrastructure that increases mobility for the whole city, without doubling traffic, and they’ll broaden housing choice and affordability for everyone.

- The developments will revitalise the city centre by channelling new demand for what is on offer there, creating jobs, growth and allowing investment in new facilities.

- Finally, they will provide generous financial compensation for those directly affected.

This social contract, Rudlin argues, creates a replicable model for “scores” of towns and cities in the UK, and would make the garden city concept a prize that cities compete for, instead of a hardship imposed top-down.Â

Walkable, busable, doable

To minimise increases in road traffic, Rudlin aimed to make walking, cycling and public transport the most convenient and economic ways of getting around. The neighbourhoods are served by bus and tram and the stop at the heart of each sub-neighbourhood is never more than 15 minutes’ ride from Uxcester town centre. The sub-neighbourhoods are 800m in diameter – a 10-minute walk across, so you are never more than a five-minute walk from a bus or tram stop.Â

The scheme also includes commercial space sufficient to create and house one job per new home built, so that many of the new Uxcesterians wouldn’t have to commute.

In Rudlin’s plan, 86,000 new homes will double the size of Uxcester within 40 years. They will be built in three urban extensions, each with a central neighbourhood and four sub-neighbourhoods (URBED)

Assuming that ‘Old Uxcesterians’ get behind the idea, Rudlin moves on to two other thorny issues. First, how to get the farmers to sell up without the promise of becoming multi-millionaires overnight, and second, how to fund the infrastructure as the new zones are built. Here we get to what may be the ‘special sauce’ of Uxcester Garden City – the economics.

Rudlin proposes the formation of Garden City Trusts that take on the role of master developers. The trusts are consortia of local authorities, people, landowners and businesses invested with the power to acquire land and access to low-cost finance.Â

Working with a large, low-interest loan from the government, the Uxcester Garden City Trust buys the land from the farmers at a per-hectare rate that reflects its current market value, with some added on to reflect its value once developed. This rate will be less than what the farmer might hope for if he or she gets lucky under the current long-winded, conflictual and risky planning system. But the farmer also holds tradeable shares in the trust so, after selling the land, he or she receives dividends as the land is developed and increases in value.

“To the landowners,” Rudlin writes, “the offer is a 100% chance to make a reasonable return on their land set against a very small chance that they might be the lucky owner that hits the jackpot.”

As for the infrastructure, the trust also comes up with the master plan and shepherds it through the necessary permissions, increasing the value of the land at a stroke. As developers are appointed and plots are sold, the revenues are reinvested in the infrastructure for future phases. This might not cover all infrastructure costs, so the trust would raise a bond over 20 to 30 years, echoing a model applied in the Netherlands.

Finally, to stop the new neighbourhoods from looking monotonous and mass-produced, the trust, who maintains the freehold, sells lots to a variety of developers, from volume housebuilders at one end of the scale down to groups of self-builders. That way, a variety of design approaches will be applied, but all of them must abide by the quality parameters set out in the master plan.

“The process would generate the natural grain and diversity that you get in a real place,” Rudlin writes. He adds: “Planning a new town is like designing a sand dune. No matter how skilled we are it somehow feels wrong.”Â

Rejected out of hand

Rudlin believes that there are up to 40 cities like Uxcester in the UK and that doubling them in size could add around three million new homes. Not surprisingly, his ideas have provoked controversy.

Perhaps because Wolfson is a prominent Conservative Party peer whose enthusiasms might be confused with party policy, the Conservative housing minister Brandon Lewis took the remarkable step of rejecting Rudlin’s vision out of hand on the very day it was announced as winner of the prize.Â

“We are committed to protecting the green belt from development as an important protection against urban sprawl,” he said in a statement, adding, “today’s proposal from Lord Wolfson’s competition is not government policy and will not be taken up.”Â

He went on to say that “we do not intend to follow the failed example of top-down eco-towns from the last administration. Picking housing numbers out of thin air and imposing them on local communities builds nothing but resentment.”Â

By characterising Rudlin’s proposals as “urban sprawl” and “top-down eco-towns” imposed on local populations, Lewis left himself open to the charge that he had not read them, or had been poorly briefed.

But he was joined by another influential thinker on urban design, the famous architect Richard Rogers (also a lord, but a Labour Party one), who called Rudlin’s idea “a ridiculous concept”, and called for extra housing to be built on inner-city brownfield land.

“You could put two new towns in the centre of Croydon without any problem because the centre of Croydon is practically empty if you look at a plan of the place,” he told the Guardian newspaper.

This week, however, an influential pair came to Rudlin’s defence, hitting back at the planning minister’s rejection of the Uxcester idea as ‘urban sprawl’.

Together, the UK’s Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) and volume housebuilder Crest Nicholson published a ‘myth buster’ statement on garden cities, which they will promote during the UK political party conference season.

One ‘myth’ they want to bust is the idea that there are enough urban brownfield site available to build on without tarnishing green belts. “Given that current demographic and population forecasts indicate 240,000 new homes will be required each year up to 2031,” says the document, “even if all these sites could be developed, they would provide land only for six years of supply.”

Their conclusion is that garden cities must be part of the mix.

What effect the imaginary city of Uxcester will have on the UK’s housing debate is not yet clear, but it will certainly be sharpened by the fast approach of the UK’s next general election in less than eight months.