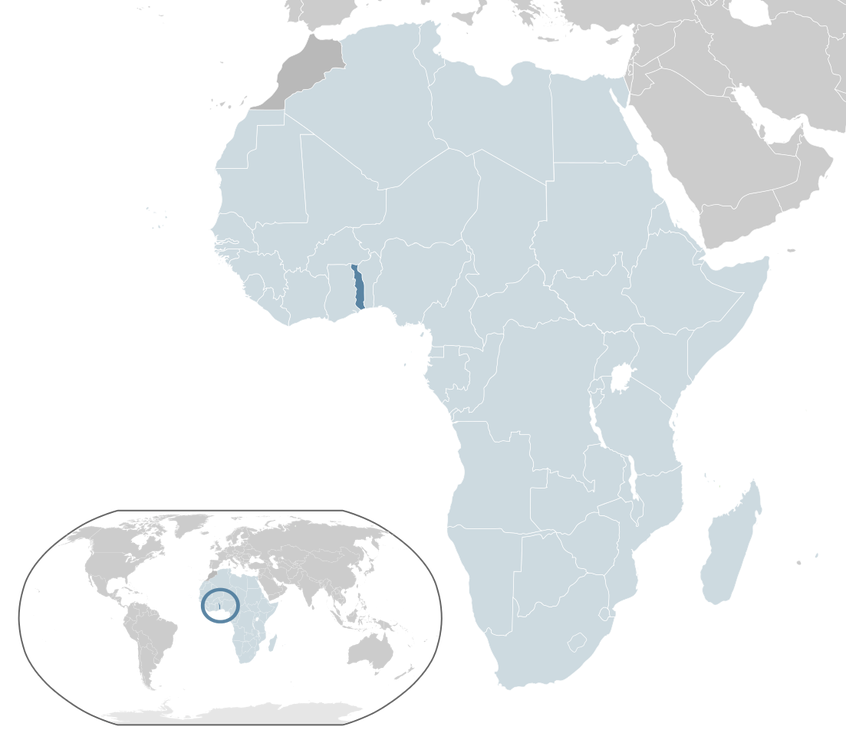

What difference will Togo’s state-of-the-art container terminal make to one of the world’s poorest counties?Â

One of the striking developments in Africa in the 21st century has been its sudden surge of growth after three decades of stagnation. The economy of the continent as a whole is expected to grow by an annual rate of 6% between now and 2023, and the World Bank expects most countries to reach “middle income” status by 2025.Â

If that prediction is to come true, many restrictions will have to be overcome. One is the absence of infrastructure that bedevils all attempts to create industry in vast tracts of Africa: most firms that want to dig a mine, for example, also have to build a power station and a railway line, which adds quite a surcharge to the usual development costs. Also missing are modern ports, which denies coastal countries the natural advantages of a seaboard, and shuts landlocked countries out of the global market. Â

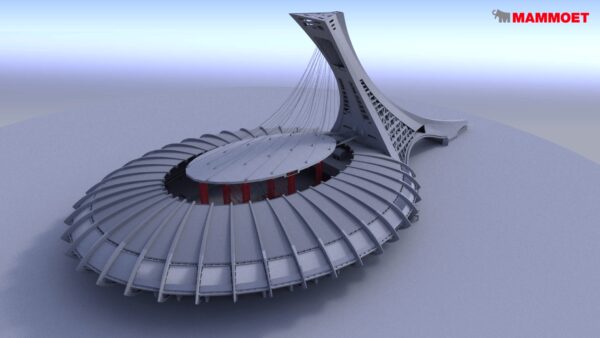

This part of the problem is about to be solved, however, by a project to construct a $380m state-of-the-art deepwater container port in the Togolese capital of Lomé. When complete, it will be one of the biggest container ports in Africa. GCR talked to Raymond Lelliott of Hill International to find out how the scheme was progressing, and what it will mean for Togo and the wider region.Â

The construction projectÂ

Lelliott has project managed the scheme, the biggest in Togolese history, since it broke ground on 26 November 2012, and he will be there when the finishing touches are put in place in May this year. He says the work is now complete on 56% of its 53ha area; in fact, enough of the quay and terminal were in place in October last year to allow the first ships to unload. Â

The construction and civil engineering is being handled by Grupo Cyes of Spain and Somague of Portugal, operating under a design-and-build FIDIC form. The only real problem they encountered, says Lelliott, was in the geotechnical department when they installed the 1km-long quay wall. Â

“At lower levels they encountered clay layers that were softer than expected,” he said, “so that required a rethink on part of the design, such as the friction angles. The clay was less sticky and there was worse adhesion for the quay wall.” Â

This led to some redesign work and an adjustment to the programme. “The quay wall, which was the main element of the scheme, is now finished and we didn’t have anything that was outside what could be expected. The port opened in October just a few days later than had been agreed in the contract.”Â

If the geology of the site hindered the scheme, it helped it as well. The land that the port was built on was accumulated by longshore drift, which is a form of natural sedimentation. And as that process is continuing, the available area will naturally expand. “Outside of our basin sand continues to accumulate, so there is a provision when there is enough sand to add a second quay in the future,” says Lelliott. Â

The sand from the dredging and excavations also provided the 4m-high platform for the terminal. “We only imported manufactured material. All the natural material was recovered from the site,” says Lelliott. “We dismantled an existing breakwater and reused that stone for our revetments.”Â

As well as materials, the project has made as much use as possible of local labour. “We also using Togolese companies as much as possible: we’ve got about 1,000 people on the site now, and I’d say about 90% are from the area. Most of the building work we gave to local contractors.” Â

The companies also made an effort to improve Lomé’s human capital. Lelliott says the project management office consists of about 30 people, of which at least half are local engineers. He adds: “The owner is using very few expats to run the port – the Togolese that are being trained to use the STSs [ship-to-shore] cranes, the RTG [rubber-tyred gantry] cranes, and all the trucks. The operators have made an effort to use as many local people as possible.” Â

The deepwater portÂ

The port will be run by a company called Lomé Container Terminal (LCT), which was set up as special purpose vehicle by Terminal Investments Limited, a port operator that is owned by Dutch company Global Container Limited. In September 2012, the Hong Kong company China Merchant Holdings took a 50% stake in the venture, and a number of its staff joined the operational team.Â

The key to getting the project going was a $270m debt package from the International Finance Corporation, which is the part of the World Bank Group that promotes private sector investment in developing countries. It arranged and led a consortium of financiers that included the African Development Bank, as well as German, Dutch and French institutions and Opec’s Fund for International Development.  Â

Lelliott says: “With a little bit of dredging of the access channel, which we’ve done, we can allow ships with a draft of 16m and 14,000 TEU [20ft-equivalent units] to come in. At the moment, the current port of Lomé can accept vessels carrying fewer than 3,500 TEU. This is the only port in West Africa that can do that. On 30 December we received a vessel more than 300m long with a draft of 15m, and the port is now full of containers.”

Togo, on the West African coast (Wikimedia Commons)

That vessel was a Panamax cargo ship, but the port can also handle the post-Panamax, ships that are too big to fit into the present Panama canal. Eventually, the port will have a capacity of 2.2 million TEU a year, which will put it about 40th in the international container port league table, with about the same capacity as Le Havre.Â

The commercial future of the port is based on the fact that regional container traffic volume has risen 10.3% a year for the past 15 years. However, less than 10% of the containers that they carry will end in Togo. Rather, the port is a regional transhipment hub, which means that the rest of the manufactured goods imported will be loaded onto smaller vessels for the journey to other ports in the region.Â

The port will certainly have an impact on Togo’s economy, but it’s important to keep a sense of proportion. About 800 jobs will be created directly, and at least 1,000 will be added indirectly as a result of the demand stimulated by the extra paychecks. However, although Togo will benefit to some extent from the lower cost of imports, it does not yet have the manufacturing base that would allow it to take advantage of cheaper exports. Â

Lelliott says: “It’s bound to grow the economy locally, but the economy of Togo is based on very little – phosphate is its main export, but that’s loaded onto bulk carriers. Â

“I can’t see the existence of the port by itself making people want to build industry – there are a lot of other economic factors that will affect that. It doesn’t have a very educated workforce, not a lot of infrastructure, minerals or natural wealth. It might generate activity in agriculture, and it will naturally become a regional centre for trade – it can build up a lot of trading companies and increase trade around the regions, but there’s not a lot of building activity yet.”Â

As a hub, the port will lower the transactional costs throughout the region, and discussions are taking place about how other countries can benefit from it. Lelliott says it will make other governments in the region consider improving rail links, especially those of landlocked countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. “We believe it is going to be a catalyst,” he said. “Landlocked countries will be given an opening to the sea and coastal countries such as Benin, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and as far down as Angola will get goods faster and cheaper.”Â

What’s more, Lomé has the field to itself. “I’ve heard of a plan to develop a similar large port in Ghana,” he said. “That’s been discussed for two years but it’s not off the starting block yet. There are discussions about a port in Nigeria but that’s not off the block either. We’re ahead of the game by several years.”Â

Life in TogoÂ

Lelliott says that in the past 40 years, he has spent only two in his native UK. The rest of the time he has spent in Spain, where Hill’s European base is situated, as well as Asia and Latin America. However, he found there was still a culture shock when he arrived in Togo. Â

“It’s a surprisingly pleasant place – it’s a small country, with a total population about 6 million, it’s very peaceful, everyone is very friendly and there are no security concerns. But there is no infrastructure and no amenities – no shopping centres or cinemas. In the evening we usually work until late, but for leisure we go out to restaurants or socialise in each other’s houses; there are local festival with dancing and singing and some people get involved in voluntary work. Â

“But it takes a few weeks to get accustomed to the standard of living. The general population has a very low standard of living. There are roads and traffic lights in Lomé, but get off the main road and it suddenly gets very poor.”Â

So, despite the predictions of the World Bank, the prospect of “middle income status” for Togo is still some way off. Ultimately, the container terminal will be a success if it becomes one of the economic forces that brings it closer.