GCR went to Dubai to meet a unique developer, and its founder, who has definite views on quality control – among other things…

Sobha Realty is a Dubai-based real estate company working on one of the most ambitious projects under way in the emirate, a mixed-used project called Hartland that will add 8 million square feet of villas, apartments and townhouses to the shores of Dubai creek – the waterway that marks the historic centre of the city.

Although the project is remarkable in its scale, what is unique about it is the way the company is building it. Sobha is the world’s only “backwards-integrated” developer. This means that rather than breaking the work into packages and tendering them to architects, engineers, project managers, contractors and materials suppliers, it is doing the whole thing itself. So, not only did it plan and design Hartland, but it is handling the mechanical and electrical engineering and plumbing (MEP) as well as the construction trades, the fit-out, the furniture and even the civils work on the supporting infrastructure.

The story of how Sobha came to adopt this approach is also the story of its founder, an Indian-born Omani billionaire called PNC Menon. He grew the company over 40 years from a furniture maker and fit-out contractor to a real estate company that can handle $4bn projects such as Hartland. GCR went to Dubai to find out more about the Menon philosophy, and to take a look at how it works in practice.

The thinking behind it

The explanation for the DIY approach Menon has pioneered is simply that he finds it difficult to trust third-party companies to deliver the level of quality that he would find acceptable. “We wanted to have total control over the design, the engineering and the manufacturing of the product,” he says. “So, we set up our own design studio – we have 90 people in Dubai – and then we have manufacturing, woodworking and contracting: everything we need to give us total control over quality. MEP is also extremely sensitive. I would not give that to anybody else, because I can’t trust anybody but myself. It’s the heart of the building. Plastering, other people can do, but MEP? No way.”

The emphasis of the interiors is on discreet good taste, rather than gold four-poster beds

In the wider construction industry, there has been a tendency for consultants to amalgamate into ever larger multidisciplinary outfits whereas main contractors have hollowed out into estimating, tendering and project management specialists, with most of the actual labour carried out by chains of subcontractors.

These developments may make sense in the strange world of construction economics, but they are not necessarily the best way of creating an industry. As has been pointed out by many reviews and reports over the years, the fragmentated nature of the industry tends to create a continual struggle between consultants and contractors over the design. And when it comes to work on site, it is often difficult to get information to flow properly through the complex networks that make up the project team, many of which will never have worked together before. Meanwhile, the individual companies that make up project teams spend their time dealing with high risks at low margins, and as a result have little time and money to invest in training and technology.

The Sobha model, by contrast, can only work if the company makes a long-term commitment to training its own workers, of whom there are some 3,000 on site at Hartland.

Jyotsna Hegde, Sobha’s president, says the company aims to provide the opportunity for employees to “learn and grow” to the limit of the capabilities. “Mr Menon always used to say if you are a smart person, you should be able to achieve your dream within this organisation for your benefit and ours,” she says. Her own career backs up that claim, since she began as Menon’s PA in 2004.

Other key staff members have been in their jobs for longer: Francis Alfred, the chief executive, joined in 2001 as a management trainee straight out of Annamalai University, Stephen Atherton, design director of Sobha Realty, joined in the early nineties. Meanwhile, Sobha Limited, the company’s Indian arm, run by Menon’s son Ravi, based its last report around the slogan “Leveraging Human Capital”.

Quality: a tough sell?

It is clear after a few conversations with Sobha management that Menon’s concern with quality has become the company’s organisational principle. Or, as they tend to say, its DNA. It would be hard to overstate this point: Sobha people see their business in a Menon-like way, and that means, among other things, the intense scrutinisation of very small details. Sobha has strict rules on everything: the weight of doors and the depth of shadow gaps around them; even its documents have a set of strict rules for typeface, font sizes, margin widths.

Living areas are notable for their high ceilings

But to return to the subject of doors, Vaibhav Setia, vice president for design and development, mentions in passing that Menon once threatened to fire any employee who touched one by anything other than the handle. In fact, Atherton says, he did commit this sin at the end of a meeting, and was merely fined for the transgression. Hegde says she was given the word during her induction. For his part, Menon says the rule is both reasonable and essential; for one thing, doors have handles for a reason, and for another we all have grease on our hands, and over time it destroys the finish …

The quality issue underpinned the growth of Sobha in the 1990s – the company’s big break came when it was chosen to work on fit-out schemes for the Omani royal family, including palaces and the new-build Sultan Qaboos mosque. Tirthankar Ganguly, Sobha’s Realty’s chief marketing officer, says this concern extends to Hartland: “Mr Menon is very clear on what he will not compromise,” he says. “Height, natural light – he thinks in cubic metres – so we have 3.5m ceilings. How can we make sure the water drains perfectly in the bathroom? That the joinery is perfect? The doors are heavy but how to make sure they move at the touch of a finger?”

That is all well and good when working on ultra-prestigious projects for ultra-demanding clients such as the Sultan of Oman. There are certain difficulties with making quality the overriding goal in a mere luxury residential scheme. For one thing, how do you sell the concept in Dubai, with its population of visa-limited workers and its ethos of rental yield and short-term asset growth? For another, how do you get customers to recognise that it is there at all, when most of it is out of sight? For example, the townhouses’ acoustic insulation is all about what you don’t hear. The air-conditioning system that keeps the villas’ interiors at 22°C when it is more than 40°C outside, is absolutely silent …

On the first of those issues, Ganguly says that Dubai’s get-rich-quick culture is changing, partly as a result of a recent decision to allow ex-pats to apply for long-term visas, which makes home ownership more attractive. For the second, he says the problem is like selling a made-to-measure suit, in which most of the tailor’s skill is not immediately apparent to most buyers.

Quality conscious: PNC Menon

He says Sobha tried to signal the fact that it was different by making the Hartland relatively low density. “What was key was first to create low and mid-rises that were as spacious as possible. And what was Dubai lacking? Green space. So, Hartland is 30% green spaces, with a serious forest with more than 3,000 trees …” Â

James Skaines, the American in Sobha’s top design team, says the sales teams presenting Hartland to clients in the US also wrestled with the problem of making quality visible. They worked with former Pixar people on virtual reality fly-throughs but found that was a “dead-end street”, for one thing, people get impatient waiting for their turn on the headset. “So, in the past 18 months we moved away from that – now we spend more money on better quality renders in virtual sales centres. We found that they’d rather see beautiful imagery.”

As advertised, the villas, houses and apartments are notable for their spacious interiors and lack of Dubai-style gold and copper bling – the décor favours a palette of Scandinavian-style creams and greys. Atherton says a lot of thought went into eliminating corridors, the configuration of behind the scenes service areas and public display spaces, and the way the buildings fit into their footprints. There are, for example, “clean” kitchens by the living room to show off to guests, and “dirty” kitchens in the utility area where the spices are fried. And instead of being plonked in the middle of their plots, as is usually the case, buildings are pushed to the side to maximise the size of the courtyard, with its garden and pool (Dubai building control took a little convincing, Atherton says).

When Hartland is built out, which will be in the next five years, all being well, it will accommodate some 15,000 people in about 6,000 apartments and 400 villas, as well as two schools, a mall, a community club and sport and leisure facilities. So far, Sobha has handed over the first phase, which has 160 apartments, and the first 100 or so people have moved in. Phase two will be 350 units and is due for delivery by October.

What next?

What will Sobha be doing once Hartland is complete? Menon says that another 10-year Dubai scheme is in the works, and an announcement may be made before the end of the year. In the longer term, he is considering a listing on the London stock exchange, and overseas expansion is on the cards.

The Hartland model in Sobha Realty’s Dubai sales office

He says: “My dream is America. There are only three countries in the world that have a future, that can expand and sustainable – India, China and the US. There is no fourth market – in the EU, each country is different. China is difficult to do business in, India is easier even for foreigners, but for maximum potential, America is the place.”

Menon is 71 now, and has taken a step back from the day-to-day running of the business. These days a lot of his time is devoted to charitable activities. He decided, before it became fashionable among billionaires, to give away half of his wealth. His particular focus is on the life-chances of women in his native Kerala, and he has built residential schools for 2,000 girls, which he plans to increase to 9,000. He says he is doing this “because we believe in karma – we have to be as good a human being as possible”.

Another form of quality …

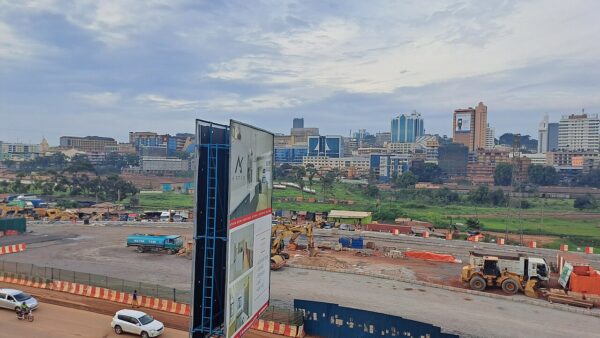

Top image: One of these villas retails for around $4m

Comments

Comments are closed.

This is thinking outside the box but will those with vested interests and connections with Regulators and those in position of power will give the approvals?

Could be similar to what may be common in many countries where if an unregistered technical professional [architect/engineer] were to design any building/infrastructure may not get the approval unless they are submitted through a professional who is registered with the relevant professional organization. Same may be true in the case of contractors

Solar energy is admitted by all to be the economical and most resources/climate friendly source of power but yet in most countries it may not encouraged but hindered with obstructive regulations or conditions.

Finally Employers give precedence and importance to academic qualifications in their job applicants but those with experience may not even be eligible to apply and if in rare cases they do get appointed they may be underpaid and made to work under a paper qualified senior.