19 February 2014

Inspired by termites’ weird collective intelligence, researchers from Harvard have shown that swarms of simply-programmed robots can build complex structures without anyone telling them what to do. Rod Sweet reports

Just as termites build large intricate structures without the queen bossing them around, so too can collective systems of robots, a groundbreaking research project has found – without the need for a central command or even individually programmed roles.

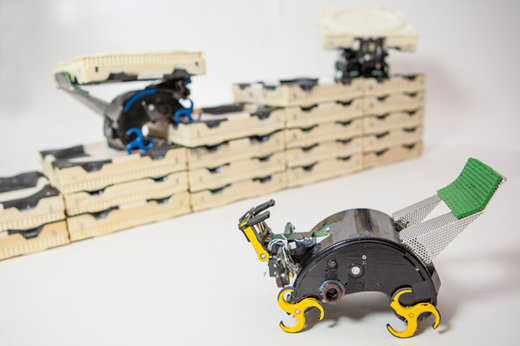

These constructor ‘bots’ build towers, castles and pyramids out of foam bricks, assembling staircases and other supports wherever needed.

Researchers say the system could pave the way for automating the building process where detailed design, engineering and supervision is either impractical or just too difficult.

Applications might include laying emergency sand-bag flood defences, or performing simple construction tasks in harsh, remote environments – like Mars.

Inspired by termites, the team of computer scientists and engineers at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, call their autonomous robotic construction crew the ‘TERMES’ system.

The results of their four-year research project has been published in the February 14 issue of Science.

“The key inspiration we took from termites is the idea that you can do something really complicated as a group, without a supervisor, and secondly that you can do it without everybody discussing explicitly what’s going on, but just by modifying the environment,” said Radhika Nagpal, principal investigator and professor at Harvard SEAS.

Termites rely on a concept known as ‘stigmergy’, a kind of implicit communication where each insect observes the others’ changes to the environment and acts accordingly.

In collaboration with Harvard’s computer scientists, electrical engineers and biologists, Nagpal’s Self-Organizing Systems Research Group specializes in distributed algorithms that allow very large groups of robots to act as a colony.

In the TERMES project the robots, each programmed with the same simple set of instructions, cooperated to build several kinds of structures and even recovered from unexpected changes during the build.

The TERMES robots can carry bricks, build staircases, and climb them to add bricks to a structure, following low-level rules to independently complete a construction project. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell, SEAS Communications.)

Each carried out its task in response to what the others did, and if one robot was removed the others just carried on, which means the same instructions can be executed by five robots or five hundred.

“When many agents get together – whether they’re termites, bees, or robots – often some interesting, higher-level behaviour emerges that you wouldn’t predict from looking at the components by themselves,” said lead author Justin Werfel, an expert in bioinspired robotics at the Wyss Institute.

“Broadly speaking, we’re interested in connecting what happens at the low level, with individual agent rules, to these emergent outcomes.”

The TERMES system is an important proof of concept for scalable, distributed artificial intelligence, the researchers claim.

The robots carry blocks, climb the structure, and attach the blocks with only four simple types of sensors and three actuators.

Their lead designer, Kirstin Petersen, a graduate student at Harvard SEAS, said this made the system reliably minimalist.

“Not only does this help to make the system more robust, it also greatly simplifies the amount of computing required of the onboard processor,” she said.

“The idea is not just to reduce the number of small-scale errors, but more so to detect and correct them before they propagate into errors that can be fatal to the entire system.”

In contrast to the TERMES system most robotic systems depend either on a central controller that can see the whole process or on all of the robots being able to talk to each other frequently.

The Harvard researchers believe these approaches can improve group efficiency but, as the numbers of robots and the size of their territory increase, they become harder to operate. In dangerous or remote environments, a central controller presents a single failure point that could bring down the whole system.

“It may be that in the end you want something in between the centralized and the decentralized system-but we’ve proven the extreme end of the scale: that it could be just like the termites,” said Radhika Nagpal. “And from the termites’ point of view, it’s working out great.”