A study by an environmental psychologist at Cornell University in the US has suggested a strong link between bad physical conditions in schools and absenteeism and low test scores among pupils.

Foul smells, mouldy walls, crumbling plaster and extreme heat or cold all signal that no one cares, which could act as a disincentive for pupils in showing up for class, concludes Lorraine Maxwell, an associate professor of design and environmental analysis at Cornell’s College of Human Ecology.

She found that poor building conditions, and the resulting negative perception of the school’s social climate, accounted for 70% of poor academic performance.

“School buildings that are in good condition and attractive may signal to students that someone cares and there’s a positive social climate, which in turn may encourage better attendance,” Maxwell told university publication Cornell Chronicle. “Students cannot learn if they do not come to school.”

You can understand why kids might think that perhaps what happens in their school doesn’t matter– Lorraine Maxwell, Cornell University

Maxwell analysed 2011 data from 236 New York City middle schools with a combined enrolment of 143,788 students.

The data included academic performance measures and assessments of physical environments done by independent architecture and engineering professionals.

She also analysed surveys on how parents, teachers and students felt about the schools’ “social climate”, using a dataset developed by the New York City Department of Education, the largest of its kind in the US.

In concluding that decrepit buildings accounted for 70% of poor academic performance, Maxwell controlled for students’ socioeconomic status and ethnic background.

“Those other factors are contributing to poor academic performance, but building condition is significantly contributing also,” she said. “It’s worth it for society to make sure that school buildings are up to par.”

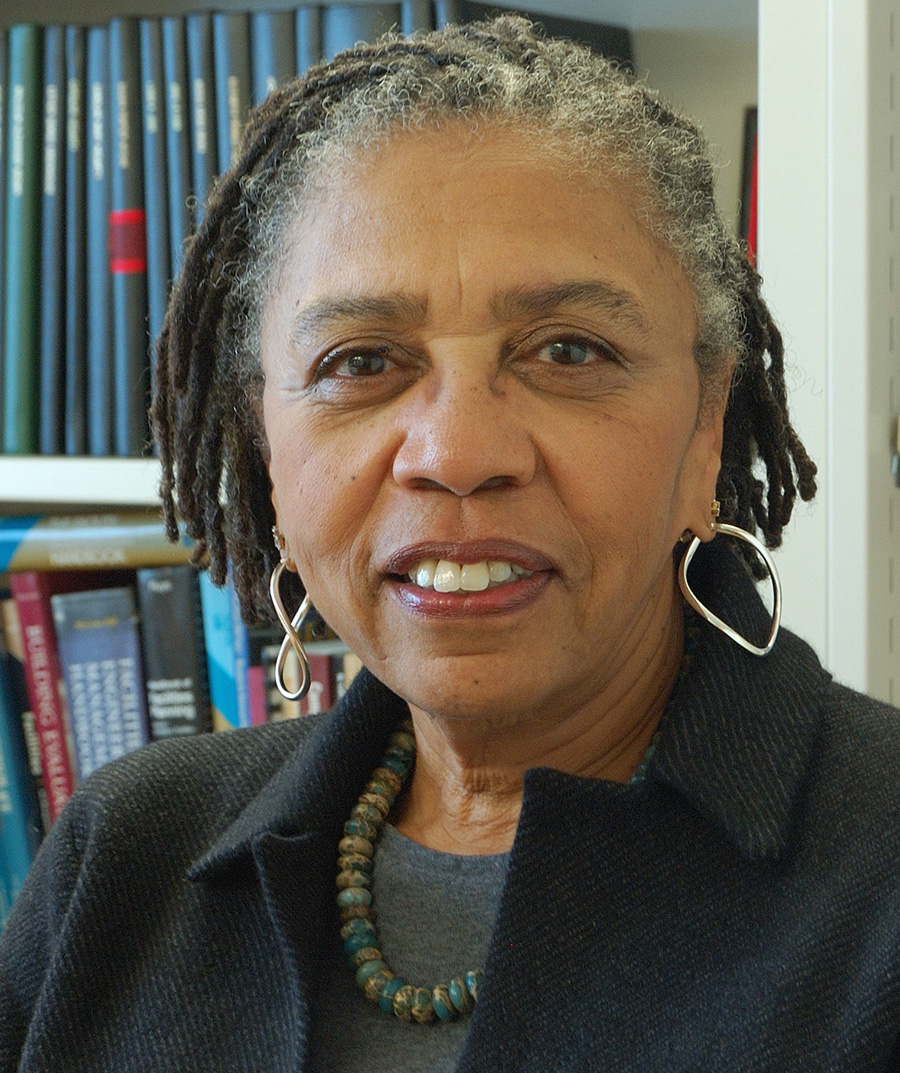

Study author, Lorraine Maxwell, associate professor of design and environmental analysis College of Human Ecology, Cornell University

Her study, published in the June issue of the Journal of Environmental Psychology, takes “social climate” to mean a school’s academic expectations, and the level of communication, respect and engagement among its students, teachers and parents.

Arguing that buildings have a strong psychological and symbolic effect, Maxwell pointed out the discrepancy between run down schools and grand government buildings in Washington, DC, and in state capitals, which are designed to inspire awe.

“Those buildings are kept well,” she told Cornell Chronicle. “Why? They give us a certain impression about what goes on inside and how much society values those activities. So you can understand why kids might think a school that doesn’t look good inside or outside is giving them a message that perhaps what happens in their school doesn’t matter.”

Policymakers must take note, Maxwell said, and understand that school conditions are especially important for children in minority and low-income communities.

“Those students are already potentially facing more of an uphill battle, and sending more positive messages about how the larger society values them is critical,” she said.

Top image: A carpenter repairs a classroom damaged by floods in Findlay, Ohio, in 2007. (John Ficara/FEMA/Wikimedia Commons)