26 February 2014

Ethiopia is motoring ahead with plans to export vast amounts renewable energy to its neighbours, and even across the sea. David Rogers reports

The news in local media last week that Ethiopia is planning to lay a cable on the Red Sea and export 100MW of electricity a year to Yemen is the latest development in the country’s ambitious plan to use renewable energy projects to transform its economy.

Across the country work has begun, or is about to get under way, on wind, solar, hydro and geothermal projects. These are all part of a 25-year plan to exploit an estimated generating capacity of 60,000MW, or about 40% of Africa’s current electricity output.

By 2040, Ethiopia hopes to be exporting $1bn of electricity to its neighbours, and consuming a large amount in its own factories.

At present the country has one of the lowest electricity consumption rates in the world. Only 25% of the population has access to the national grid, and the World Bank estimates that Ethiopa has a per capita consumption of 52kW every year, compared with 4,694kW in South Africa.

Over the volcano

One of the most eye-catching schemes is a plan to install a geothermal power plant in the caldera of the active volcano in the Rift Valley, about 200km south of Addis Ababa.

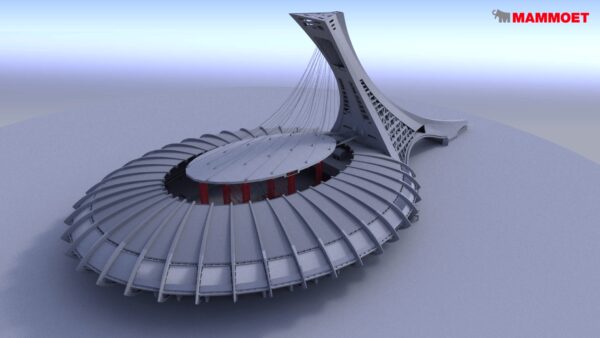

The ‘Corbetti’ scheme, as it is called, being undertaken by an Icelandic company partly owned by American investors, will eventually produce 1,000MW of power, making it by far the largest in Africa. Reykjavik Geothermal signed a 25-year deal with the Ethiopian government in September last year.

Only surface exploration has taken place so far, but Gunnar Gunnarsson, chief executive of Reykjavik, is confident about Corbetti’s potential. He says that its geological conditions are ideal, that geochemistry studies show the water to be exceedingly hot, and that studies suggest the reserve is vast.

The plan is to undertake the work in a number of stages. A 10MW plant is expected to be operational by 2015, increasing to 100MW in 2016 and to 500MW by 2018, by which time about 100 wells will have been dug. The second 500MW phase of the project is expected to be completed by 2021. Altogether, the work is expected to cost $4bn.

Michael Debretsion, Ethiopia’s deputy prime minister, said: “This will be a significant step in realising our strategic vision of being the regional leader for power generation and export in East Africa. We believe Ethiopia has over 10,000MW of geothermal potential which provides base load power and is a perfect complement to our 50,000MW of hydropower potential.“

Wind and water

Elsewhere in Ethiopia, a 120MW wind farm, also the continent’s largest, started turning in October last year. The $290m Ashegoda scheme was built by French firm Vergnet and was financed by a low interest loan from BNP Paribas and the French Development Agency. The Ethiopian government covered 9% of the cost.

It has been estimated that Ethiopia is the third largest wind generator in Africa, behind Egypt and Morocco, and the government plans eventually to generate 800MW of wind power.

How the $4bn Corbetti geothermal scheme will look when it is completed in 2021 (Ethiopian government)

The centrepiece of Ethiopia’s plan is the 6,000MW Grand Renaissance Dam, which is under construction on the Blue Nile and due to be completed in July 2017. This has been the subject of a long-running row between Ethiopia and Egypt over a potential loss in the volume of the Nile owing to evaporation in the dam’s reservoir.

The latest word in this dispute was delivered by Ethiopian prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn, who told journalists earlier this month that Ethiopia and Egypt had “no option except dialogue and negotiation to provide a win-win solution over the project”.

In the solar field, two US companies have been awarded a contract to construct and operate three 100MW photovoltaic power stations. The contract was awarded to Global Trade & Development Consulting and Energy Ventures by the Ethiopian Ministry of Water and Energy and the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation.

In January last year, Ethiopia began manufacturing photovoltaic panels for the first time, reports Cleantechnica.com.

Where the money’s coming from

To support the electricity export plan, the African Development Bank and the World Bank are providing finance for the distribution network.

This includes $1.5bn for a grid link to Kenya with the capacity to transport up to 2,000MW of power. Ethiopia also plans to increase its power exports to Djibouti, Kenya and Sudan, and establish grid links to South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, as well as that cable to Yemen.

Altogether, about $22bn is planned for a pan-continental electricity highway by 2020, reports the Financial Times.

Donald Kaberuka, president of the African Development Bank, told the FT that this is the first time an African government has looked “at energy as an export sector the way you export gold, and it’s going to be a huge advantage for them”.

The African power context

The Corbetti geothermal scheme will be the first project to be developed under the US government’s Power Africa initiative, which was launched last June by President Obama in a speech at Cape Town University. This makes $7bn available to support power schemes in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria and Tanzania.

The money includes $1bn in investments from the Millennium Challenge Corporation, $1.5bn in financing and insurance from the Overseas Private Investment Corporation. However, the lion’s share of the money, $5bn, is to go on support for American exports.

It is reckoned that this has secured more than $14 billion in commitments from private firms, including General Electric, which plans to generate 5,000MW in Tanzania and Ghana; and UK-based Aldwych International, which says it will invest $1.1bn to develop 400MW of wind power in Tanzania and Kenya.

The International Energy Agency estimates that it will cost $300bn to provide universalelectricity access to the entire population of Sub Saharan Africa.

According to the agency’s World Energy Outlook 2013, about 1.7bn people are expected to gain access over the period to 2030 but in many cases these gains will be offset by population growth, leaving about 1bn people without access to centrally generated power.