Over the course of 2015 work has been under way on what appear to be five miniature oil platforms 5km off the coast of tiny Block Island in the northeast corner of the US.

It won’t be until they reach their full height of 80m, and are fitted with large, 6MW wind turbines, that it will be clear what these towers in the Atlantic are for.

But even then, their significance is likely to be lost on a casual observer.

That’s because this is the first commercial offshore wind energy project ever built in the US. It is small, but fans think it’s beautiful, and there may be many more like it sprouting on the American continental shelf in the years to come.

The Block Island wind farm really is just the start of a new industry and we’re excited to be at the forefront of that here in the Ocean State– Deepwater Wind

Welcome to the Block Island scheme, a 30MW, $290m wind farm being developed by Deepwater Wind, a company set up by a group of investors interested in the possibilities of the offshore market, including the giant hedge fund, DE Shaw.

Work began in the spring of 2015, and Deepwater says it’s on track to begin generating power by the fourth quarter of this year.

“The Block Island wind farm really is just the start of a new industry and we’re excited to be at the forefront of that here in the Ocean State,” a spokesperson for Deepwater Wind told the local AccuWeather website.

It’s not hard to see why investors in the renewable energy sector might be interested in the possibilities of America’s sea breezes.

Writing in Nature, science journalist Gene Russo asserts that if the US were to exploit all its offshore resources, including in more difficult deep-water sites, it would be able to generate more than 4,000GW of electricity, which is about four times more than it needs to power the entire country, or 70% of the entire world’s installed capacity.

If he’s right, it will bother many that all that energy is wasted on little more than moving sailboats around.

In northwest Europe, by contrast, wind power has latterly been growing by around 20% a year.

Since 2009, Germany, Belgium, Denmark and the UK have installed 25 offshore farms with a capacity greater than 200MW, and the Netherlands is presently working on the giant 600MW Gemini scheme, which will be the second largest in the world after the even more gigantic 630MW London Array.

The base of one of Block Island scheme’s turbine towers being towed out to sea last year (Deepwater Wind)

In the future, the North Sea may be more significant as a source of wind energy than it was for oil: according to a 2009 report by the European Environment Agency, by 2030 the UK alone could have a potential of close to 5,000 terawatt hours from wind, although that assumes wind farms can be installed in much deeper water and much farther out than is the norm today.

The US Department of Energy would like America’s wind industry – which is dynamic enough onshore – to follow Europe’s lead.

It released a report in September last year which noted that there are 15.7GW of offshore wind schemes in “various stages of development”. Of these some 13 projects with 6GW of capacity have reached an “advanced phase of development”; 3.3GW are expected to be operation by 2020, and 86GW by 2050.

Standing in the way of this target, says Russo, is a combination of “environmental concerns, bureaucratic tangles and political opposition”.

US firms have had to deal with different approaches in every state with a coastline, and the federal government and its agencies have not succeeded in building an overarching framework.

The success of renewable schemes therefore depends on governments joining up their tax, energy and environmental policies, and the nascent US offshore wind industry getting the ears of state and federal governments.

The Block Island scheme may be a harbinger, but it is also somewhat unusual. For one thing, it’s solidly backed by the State of Rhode Island. For another, it has local support.

The locals in this case are the thousand or so year-round residents of tiny Block Island itself, a 25-sq-km summer-holiday hotspot 21km off the Rhode Island coast.

Today, residents rely on a fume-belching diesel power station, which produces electricity at a higher cost than elsewhere in the US. When the five turbines start sending electricity by submarine cable to the mainland, enough will be diverted to let the island’s diesel generators retire.

For Block Islanders, the prospect of greener, cheaper power is well worth the occasional glimpse of a turbine on the horizon.

For a better representation of the challenges facing offshore wind in the US, we need to look at a far bigger scheme planned just up the coast, in waters off the state of Massachusetts.

Siege of Troy

The benighted Cape Wind scheme was the most ambitious of all US projects considered to be “at an advanced stage”. However, with permit applications filed in November 2001, the $2.6bn project, sited around 8km off Cape Cod in Nantucket Sound, sparked a struggle that has outlasted the siege of Troy.

The 1,000 residents of Block Island, which is pictured here, will get cheaper, cleaner power from the Deepwater Wind scheme (Timothy J. Quill/Wikimedia Commons)

Comprising 130 turbines, the 454MW scheme attracted powerful opposition, not least from fossil-fuel billionaire William Koch, whose extensive waterfront estates overlook the Sound.

Criticising Cape Wind as “visual pollution“, Koch has chaired the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, and is reported to have donated around $5m in lobbying against it.

Other powerful opponents included presidential hopeful Mitt Romney, while he was governor of Massachusetts.

Cape Wind is a prime example of how offshore wind schemes can fall through cracks in the state-federal regulatory mosaic, especially if foes with deep pockets are determined to set up legal tripwires.

As well as books and movies about Cape Wind, there have been 32 legal cases against it, of which embattled developer Energy Management Inc. claims to have won 26.

Despite these difficulties, by March 2014 the developer had secured loan commitments totalling an estimated $1.3bn – half the total needed – from a clutch of optimistic investors including the Netherlands’ Rabobank, Danish Export Credit Agency, EKF, and the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi.

But in January 2015, the scheme had its commercial rug whipped from under its feet when two power companies, National Grid and Northeast Utilities, cancelled their contract to buy power from Cape Wind, accusing the developer of failing to meet obligations on securing financing and starting construction.

Cape Wind pleaded that “relentless litigation” had prevented its hitting agreed milestones, but the power companies’ decision has stuck. In February that year Cape Wind president Jim Gordon told a rally of 300 supporters that “We have only begun to fight”, but the company has issued no new announcements since.

Enter the Danes

But developers sense there is money in wind, and so there may be no holding back America’s offshore turbine revolution.

A third scheme in the region has got off to much more promising start. This is the Bay State Wind project, intended for a site some 24km off the coast of Massachusetts’ affluent island, Martha’s Vineyard.

Behind this scheme is Europe’s leading offshore wind developer, Dong Energy, of Denmark – a veteran of more than a dozen offshore wind farms in the UK, Denmark and Germany.

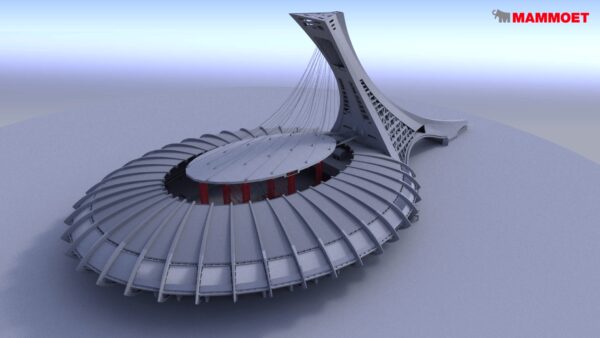

Go and do likewise: the 630MW London Array: at present the largest offshore wind farm in the world (William Hall/Wikimedia Commons)

The US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management assigned Dong a license for the site in June 2015, and feasibility studies are now underway.

The plan is to anchor 100 turbines in water depths of up to 165 feet. If it goes ahead, Bay State Wind will be the biggest offshore power scheme ever built, and will have a 1GW generating capacity – double Cape Wind’s – because the wind there blows faster and steadier. Dong says conditions are quite similar to the North Sea.

Crucially for the project’s success, it is thought to be far enough away from the sundecks of the well-to-do so as to be mostly invisible to the unaided eye. The Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound gave it bland praise, calling it a “much better site with fewer conflicts” – no doubt to Dong’s relief.

Dong is financing the scheme itself, which will also bolster its prospects.

According to Dong, construction will take about three years, with the first third of the project ready to come online early in the 2020s.

If Dong can pull this off, it will be a precedent of strong allure to investors. If not, then Gene Russo’s 4,000 potential gigawatts will just keep blowin’ in the wind.

Top photograph: The Walney wind farm off the coast of Cumbria, UK, in the Irish Sea. The US wants to follow Europe’s lead on offshore wind (Wikimedia Commons)

Comments

Comments are closed.

Judging by the huge drop in oil prices – fossil fuel suppliers need to rapidly adapt or die! Instead of spending their money opposing wind turbine generation they would be better advised using whatever

resources they have yet available to develop even more effective and competitive wind turbine generation

schemes of their own and to stop trying to hold back the inevitable!!! Viva competition!

The technology developed and construction experience acquired in deepwater drilling platforms is undoubtedly relevant and valuable to offshopre windfarms.

Given the environmental pressures the oil industry would be well-advised to ditch the King Canute attitude, face the facts, jump on board, and grab a piece of the action before they miss the boat that is filling with other entrepreneurs who are catching up with that (increasingly)deep water construction experience.

(Sorry for all the metaphors.)