Construction firms may have to learn to build a new and complex type of car-fuelling station as Japan and the US move on plans to enable cars powered by fuel cells.Â

Toyoto and Honda are planning to launch fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) next year, and South Korea’s Hyundai has already made its Tucson marque available for lease in small numbers.Â

Toyota has said its vehicle will be available for less than $100,000. Mercedes Benz has produced limited numbers of its conventional models fitted with fuel cells. Meanwhile, General Motors, Nissan, Renault and others have said they will bring a version to market in the next three years or so.Â

To prepare for these launches, Japan and California have set their sights on a 100-station network. Japan said it intends to complete its version by March 2016, and the state government of California has committed itself to providing up to $20m a year until it also reaches that number.Â

In May, the California Energy Commission (CEC) announced awards for 28 stations, to be built by November 2015, for a total of around $46m. CEC will also provide funding to keep the stations operational during a long loss-making period. California presently contains nine of the US’s 11 facilities.

Japan is to site its hydrogen refuelling points in the country’s largest cities to support the launch of FCVs in March next year. The country has constructed about 10 facilities so far. The latest is being built by Toyota Tsusho, the general trading arm of the Toyota group, in the industrial centre of Nagoyo, about 70km east of Osaka. The French company Air Liquide will supply the fuel.Â

Koji Nakagawa, the general manager of Toyota Tsusho, said he believed “hydrogen has a huge potential as an alternative energy source”. He also said Toyota planned to offer hydrogen at a price that was competitive with gasoline, and that he believed the venture would begin to turn a profit in about six years.

One striking fact about the Californian stations is that only three out of 28 are being run by conventional energy companies. Instead, car firms have taken them on, or start-ups have emerged to build and manage the new retail hydrogen outlets. One early leader is FirstElement Fuel, which was launched with support from Toyota.

A Hyundai ix35 fuel cell car about to be refuelled by an ITM Power HFuel pump (Source: Bexi81/Wikimedia Commons)

In Europe, the lead has been taken by Germany, partly to support the limited number of FCVs produced by Mercedes Benz. It has set a target of 100 stations by 2017, and the North Rhine-Westphalian government has created the 230km “NRW Hydrogen HyWay” in the Rhine-Ruhr area. Italy has completed a hydrogen filling station in Mantova on 21 September 2007, and has designated the A22 motorway between Modena and Verona as a hydrogen route.

South Korea plans 43 by the end of 2015, according to the International Partnership for Hydrogen and Fuel Cells in the Economy.Â

Building a hydrogen fuel station

The process of building a hydrogen fuelling station is much more complex and expensive than building the hydrocarbon or biofuel version. At present, the Californian experience is that it takes about two years to construct a facility.

Stations are all above ground, and can either store liquid hydrogen that is brought in by tanker or they can produce it themselves, in which case the filling station is, in effect, a small chemical plant, with all the safety requirements that that suggests.Â

In particular, hydrogen is odourless and highly combustible, and will be stored at high pressures. This will mean that hydrogen, which is stored in above-ground tanks, will have to be at least 15m from anything else on the forecourt.

The present capital cost of building a station able to produce 450kg of hydrogen a day is $2.8m according to a recent report by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory.Â

Fuel cell vehicles

FCVs are an evolution of the electric car, with the fuel cell acting as a battery. Its advantage over a conventional battery is that that instead of lengthy recharging, it can simply be refilled with hydrogen. And as with a conventional electric car, it produces no emissions apart from heat and water.

Honda’s FCEV concept car, unveiled last year’s Los Angeles motor show. It has a 300 mile range and a refuelling time of less than five minutes

Proponents of fuel cell vehicles, which are being developed by most major manufacturers, say they offer advantages over battery-powered electric cars, including the fact that they can travel roughly as far as gasoline-powered cars on a single, rapid refill. Electric cars require more frequent and often more time-consuming recharges.

The 350-bar hydrogen tanks for FCVs contain enough fuel for a 399km journey, and the 700-bar tank, which seems to have become the industry standard, has a range of 678km.Â

This allows a route to be designated as suitable for FCVs without building a lot of stations – although a driver who ran out of hydrogen between stations would be in something of a pickle.Â

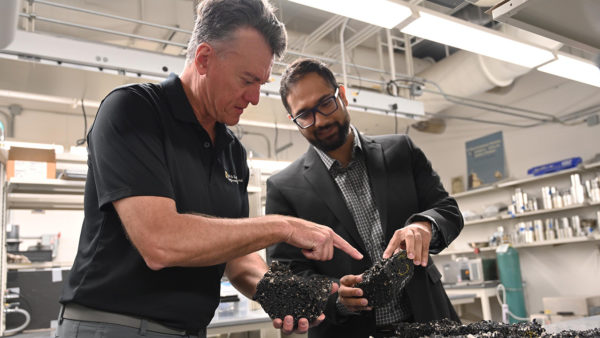

The overall environmental performance of the system depends on how the hydrogen was itself produced. It is possible to make hydrogen from renewable energy, and Toyota Tsusho has experimented with producing it from sewage sludge using biomass gasification technology.

Some prominent car makers have expressed doubts about the suitability of fuel cells for powering vehicles. Rudolf Krebs, who is leading Volkswagen’s electrification efforts, has argued that the need to convert energy into hydrogen in the first place, and the need to compress the hydrogen to a pressure of 700 bar and store it in the vehicle all costs more energy.Â

Finally, he has said, “you have to convert the hydrogen back to electricity in a fuel cell with another efficiency loss, so that in the end, from your original 100% of electric energy, you end up with 30 to 40 percent”.

The principle of the fuel cell has been recognised for some time – the first vehicle fitted with one was a farm tractor in 1959. Its first limited commercial application was in providing power to isolated environments that required zero emissions, which meant space stations and the US space shuttle programme. Vehicle manufacturers began looking at the feasibility of using them to power cars in the 1990s.

Comments

Comments are closed.

I think the real problem with renewable energy is that the existing energy suppliers will have to run down the economic life of their existing investments before they will allow freehand on renewable. This seems to be happening with any old industry that is bringing in new products (Drum Brakes v Disc Brakes) — new products into old markets —