Researchers from the University of Missouri’s College of Engineering have been given a $1.2m grant to develop environmental product declarations (EPDs) for asphalt made with ground rubber tires.

Their goal is to measure how much CO2 and other greenhouse gases are emitted both when roads are built and when tires are ground up.

The grant comes as the US government is pushing the construction sector to embrace lower-carbon materials.

EPDs act like nutrition labels for construction materials, said Punya Rath, an assistant research professor who works in the college’s Asphalt Pavement and Innovation Lab.

“Food labels are highly visible and will tell you about the product — it has this many grams of sugar, this much sodium and so on,” he said. “EPDs will tell you how much CO2, nitrogen dioxide and other gases are emitted during the production of rubber-modified asphalt mixtures.”

He said the data already exists for traditional asphalt mixtures and can be found in a national database.

The US Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has also allocated funding to increase the use of low-carbon construction materials.

“For the FHWA to enforce low-carbon materials, there has to be some way to quantify it,” Rath said. “How are you going to say which asphalt is less carbon-intensive? We need a scoring system to make that comparison.”

350 million tires a year

To get the data, researchers are working with the US Tire Manufacturers Association, as well as Michigan Technology University, and the Scrap Tire Research and Education Foundation.

More than 350 million tires are produced in the US each year, with limited uses for discarded ones.

“The transportation industry produces about 500 million tons of asphalt per year,” Rath said. “We could use a significant number of scrap tires, if not all, that the US generates.”

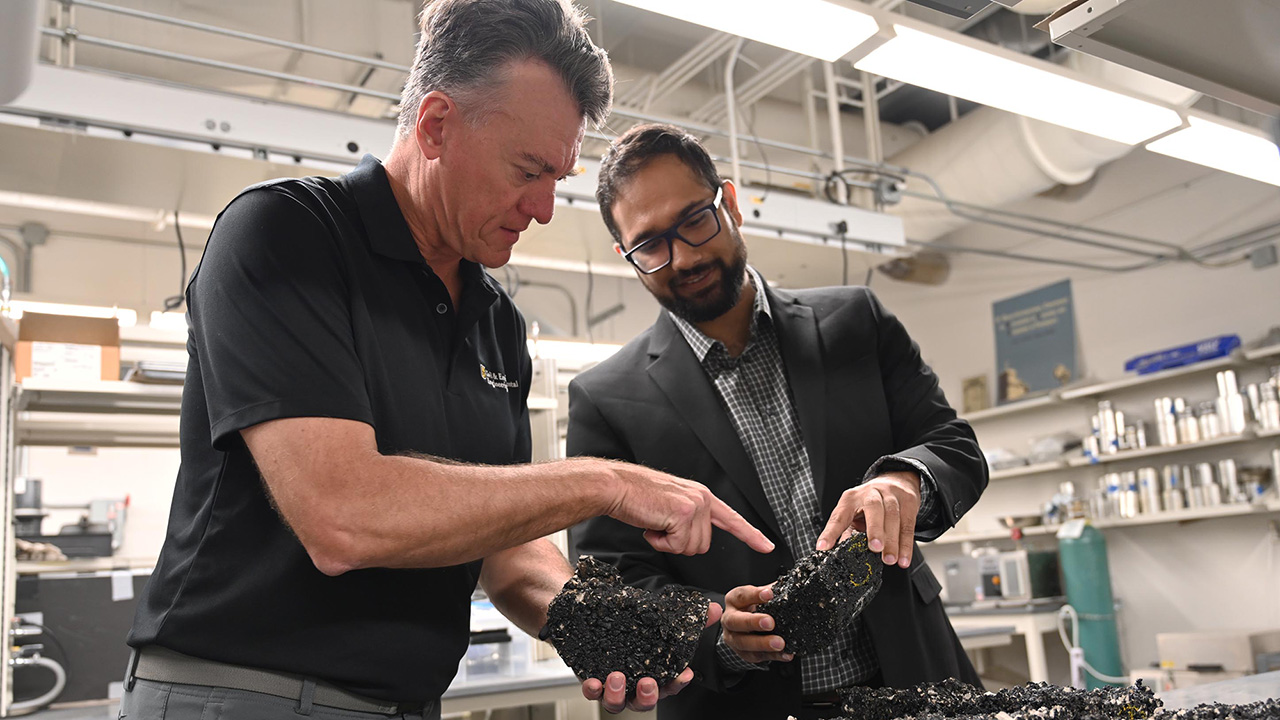

Bill Buttlar, a professor the College of Engineering, hopes findings could pave the way to rubberised roads.

“Rubber-based roads have been around for more than three decades, it’s just that the amount of this material has been relatively small,” said Buttlar, who is the Glen Barton Chair in Flexible Pavement Technology.

“In the US, growth of rubber-modified asphalt has been slow. Now, the increased focus on sustainability is creating a demand for it.”

Where rubber meets the rubber

To test the viability of rubber-modified asphalt, Buttlar and his team have been working on several road projects across Missouri, including a 1.4-mile stretch on Stadium Boulevard in Columbia.

In Kansas City, crews recently laid asphalt containing both rubber and recycled plastic along a municipal road.

Additionally, rubber-modified asphalt has been used along interstates 44, 70 and 155, as well as US Highway 63 near Rolla.

Buttlar said studies have shown that rubber-modified asphalt roads can last up to two times as long as traditional asphalt surfaces, which results in less construction and fewer potholes.

Rubber also makes the roads smoother, meaning less wear and tear on vehicles and tire treads.

- Subscribe here to get stories about construction around the world in your inbox three times a week

Further reading: