A report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) into the cost of generating electricity in different countries has found that the UK’s third generation nuclear plants, 11 of which are expected to be built over the next 15 years, will be the most expensive in the world.

The report comes as the company building the first of the UK’s new nuclear plants, France’s EDF Energy, has admitted that its new plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset will not start generating power in 2023, as planned, sparking concerns over the UK’s prospects for power supply in the medium term.

Commissioned by the OECD, the report looked at nuclear, fossil fuel and renewable power generation in the 19 OECD member countries, as well as China, Brazil and South Africa.

The nuclear portion of the OECD’s report looked at plants being built now.

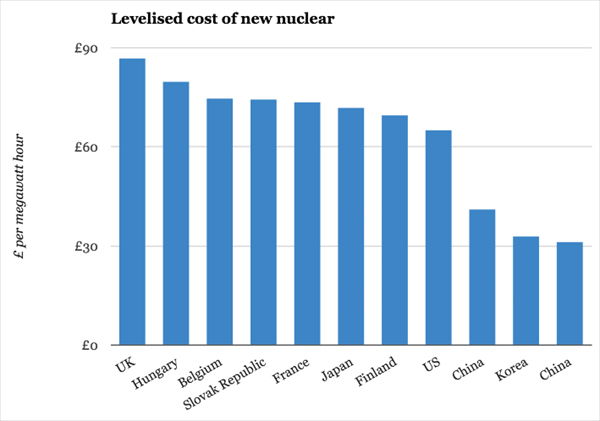

A comparison of average levelised lifetime costs found that nuclear power would cost almost £90 ($136) per MW hour for the UK’s new plants compared with a little more than £30 ($45) for China’s.

Projected levelised costs for new nuclear capacity. The figures assume a 10% discount rate (Source: Carbon Brief)

The report puts forward a number of reasons for the wide disparity in costs.

One is the high capital cost of financing nuclear construction in the UK: the UK will use private sector lending by private sector companies, leading to expected borrowing costs of 9.5%, compared with 6% in the Republic of Korea, and close to zero in China.

The impact of borrowing costs has led to calls to take construction of the plants into state hands.

One left-of-centre think tank, the Institute of Public Policy Research, has argued that the government should take the third generation plants into public ownership and outsource their construction and running to the private sector rather than relying on future electricity users to fund the schemes.

Another factor is inflation. In the case of the $39bn Hinkley Point C scheme, EDF will be paid a guaranteed rate for its power for 35 years, and this will rise in line with the UK retail prices index.

The Carbon Brief website estimates that, on current trends, this will mean the price that EDF receives in 2023, when the station was due to open, would be £123 a MW hour.

Other possible reasons suggested include that the UK’s numbers may be more up to date and accurate, and that other countries’ estimates include certain types of state subsidy.

Hinkley Point delayed again

Meanwhile, EDF Energy admitted this week that Hinkley Point C, expected to be the first of the UK’s new generation of nuclear plants, would be delayed.

It was supposed to begin generating power in 2023, but a Final Investment Decision (FID) has still not been reached, UK media reported this week, citing protracted negotiations with EDF’s Chinese investment partners and an EU state aid inquiry.

It’s not the first delay. An expected FID was put off in February this year owing to reported difficulties in negotiations with Chinese investors.

Under the terms of an agreement reached in October 2013, China General Nuclear and China National Nuclear Corporation will take a combined 30-40% stake in the plant.

EDF said agreement with the Chinese had still not been reached, leading to speculation that a deal may be announced when Chinese president Xi Jinping visits the UK on 20 October.

Jean-Bernard Levy, EDF’s chief executive, said: “Even though the final investment decision has been pushed back from the initial forecasts, the construction time will stay the same, which means that the commissioning date will be updated at the point when the final investment decision is made.”

Another potential problem with the plant is the safety of its reactors. The plant will have two EPRs, made by French firm Areva, with a total capacity of 3.2GW. On Thursday, EDF said the reactor designs would not be finalised until late 2018.

Keeping the lights on

The UK government is running out of time to install new generating capacity. The existing nuclear power stations, which provide about 18% of the country’s electricity, contain 16 reactors, 14 of which are due to be shut down by 2023.

This is the same year that its old coal-fired stations are due to close under EU air quality rules.

The UK already has one of the lowest per capita generating capacities in the developed world – 5,425kWh a year – which puts it in 35th place, between Greece and Montenegro, according to the World Bank.

Alternatives?

The report also found that there had been a significant decrease in the cost of renewable generation as a result of technological advancement.

It found that solar costs had decreased the most, but that onshore wind remained the cheapest form of renewable power.

On average, the cost of renewable power is now equal or less than fossil fuel in many cases.

It also found that the cost of nuclear power were “roughly on a par” with the level they were at in a 2010 study “thus undermining the growing narrative that nuclear costs continue to increase globally”.

The report looks into the likely cost of small modular reactors, or SMRs, which could be deployed as early as 2023.

It finds that the costs of a MW are likely to be up to twice that for a large reactor, but that economies of scale and lower capital costs may mean that “SMRs are expected at best to be on a par with large nuclear if all the competitive advantages are realised”.

Image: A CGI view of Hinkley Point C (Source: EDF)

Comments

Comments are closed.

It is difficult to comprehend the actions of the government in the matter of UK electricity supply, that is if you only look at supply, then at least half of the equation – demand – is invisible to you. Add in the overall energy picture in the UK, where electricity generation by the big suppliers is small compared to transport or heating useage, and you begin to get some sort of idea that in fact, hmg is doing a very good impression of a latter-day Nero on a violin.

The new reactor at Hinckley is basically yet another vanity project, along with such delights as HS2; designed primarily to obfuscate the fact that the government is doing nothing about the things that matter. Simple things, like making the electricity grid fit for the diversified renewables of the 21st century, are worthy – at present – of only an obscure and unreported ‘call for evidence’ by Whitehall. When in fact we should have got on with installing the revised networks, and the energy stores – that make renewables work – a decade or more ago. Its not even science, let alone rocket science, just simple application of things already in the technology cupboard.

Even if nuclear were a sustainable way forward, and denying future generations a say in how much radioactive waste they have to deal with, while getting nothing for their pains is hardly construable as ‘sustainable’, putting new capacity the best part of two hundred miles away from where the energy will be used, is not. Guaranteeing the current overall thermal efficiency of such plant will be around the 25% mark, when it could be 90+ if sited alongside the users, in say Battersea, is not exactly a leap of faith in the safety of the technology. Or a great leap forward in thermal efficiency. Possibly even a great leap back.

If the supply and network side is pretty simple to address, then demand is child’s play; Insulation, LED lighting, providing gadgets with controls that turn them off. All of these would provide jobs in the UK, and the lower our energy needs, the easier it becomes to provide them with renewables.

It really is time we stopped playing the power game; since the grand allies of the eighteenth century it has been easy to make a fortune selling energy. It is now easy for everyone to take responsibility for generating the energy they need from renewables, so we can not only close the coalhouse door, but the gas valves and reactor cores as well. And not miss them