5 June 2013

Construction legal expert Metehan Sonbahar, who took part in the early days of the protests, explains how a secretive approach to urban development backfired so spectacularly.

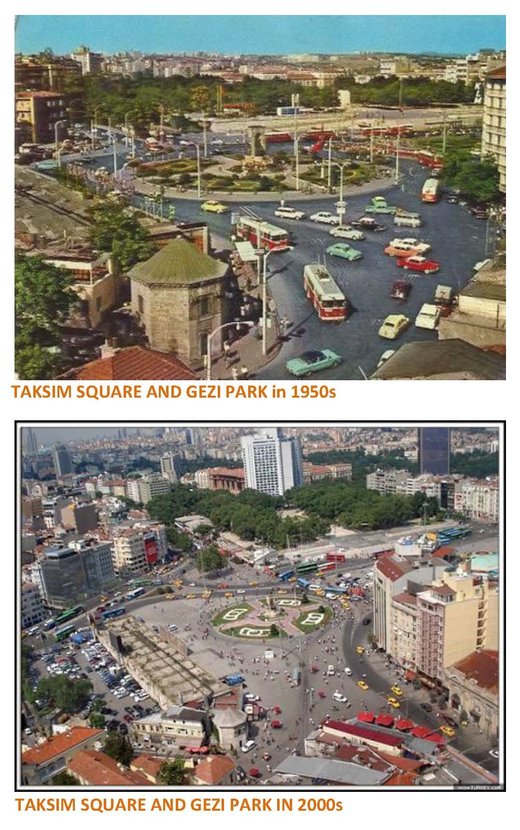

Taksim Gezi Park is an urban park located next to Taksim Square in the BeyoÄŸlu district, in the heart of downtown Istanbul.

It’s a site of symbolic importance.

In 1806 a military barracks was built there by the Ottoman Sultan Selim III.

Later in the 19th century, having been damaged by fire, the building was rebuilt in a mix of Ottoman, Russian and Indian styles.

In 1921 its internal courtyard was transformed into the Taksim Stadium, the first football stadium in Turkey.

All major football clubs in Istanbul used it, and in 1923 the Turkish National Football team played its first ever international match there.

The barracks were demolished in 1940 and the construction of Taksim Gezi park was completed in 1943, giving residents of Istanbul a free, open, green space – the first in Istanbul built after the establishment of the Turkish Republic.

Despite the limited resources of those days, the park was very cosy, with trees, flowers, attractive features and views of the Bosphorus.

It was immediately very popular amongst Istanbulites.

Not officially revealed

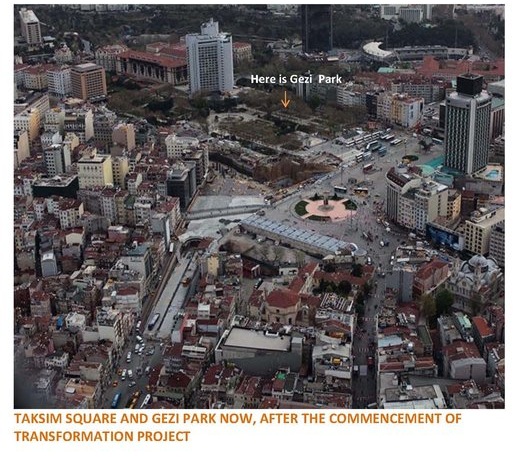

In September 2011, Istanbul Greater Municipality decided to develop the park as part of an urban transformation project.

The development would feature a replica of the 19th century barracks, and would contain a shopping mall, museums, car park and an ice skating area.

The project was not officially revealed to the public, but some journalists discovered the details when it was submitted to the General Directorate of Preservation of Cultural Assets for review in November 2012.

Barracks at Gezi Park, 19th Century

A few newspapers ran the story but it was not enough to attract much public attention. In media outlets considered friendly to the government it was not covered at all.

What media coverage there was focussed on the plan to make the historic square car-free. I believe media were trying to portray a side of the development they knew people would like.

On 17 January this year the General Directorate of Preservation of Cultural Assets tried to block the project on the grounds that Gezi Park was an asset for Istanbul, providing a rare green space in the congested downtown area.

Istanbul Greater Municipality appealed against this and on 1 March 2013 the higher commission overruled the General Directorate and said the development could go ahead.

Again, this decision was not published by media supporting the government. Only a few newspapers reported the decision of the higher authority. I heard several tiny criticisms from academics, architects, engineers and artists, but that was it.

For the public there were no details, which made people think something was being hidden.

When construction started, people saw trees being removed and the park being demolished, and that triggered the protest.

Barracks courtyard becomes modern Turkey’s first stadium, 1921

Where you can breathe

When the plans were revealed it was clear the new barracks were to be five storeys tall, and the towers 10 storeys.

This height is a problem for a number of reasons.

Taksim Square is considered to be the heart of the city. Millions of people come every year, tourists and locals. The surrounding area is already occupied by tall buildings and there are not many places left where it feels open, where you can breathe.

This plan would see Gezi Park as a green, open space disappear completely.

Not only that, the new barracks are designed to surround Gezi Park fully, meaning a free, public space will become a closed, commercial space.

On 27 May the wall standing on one side of Gezi Park was demolished and a number of trees were removed. A group of up to 50 people started protesting against the destruction of the trees and the park. They spent the night there in tents.

In the morning of 28 May, there were more protesters. They stopped demolition. Police intervened to remove the protesters.

On 29 May police started using tear gas and water cannon. Protesters’ tents were burned that day.

(Montage credit: Metehan Sonbahar)

Around 5am on 30 May police attempted again with tear gas. But this did not stop the protesters coming to the park. By evening the number of protesters had dramatically increased.

On 31 May, protests spread over the country.

That day Istanbul 6th Administrative Court ordered temporary suspension of the development.

But the number of protesters continued to grow. On 1 June, protesters from Asian side of Istanbul walked across the bridge over the Bosphorus Strait to Taksim.

Over the next two days the protests spread to 48 states in the country, with the intensity of the clashes between the protesters and the police increasing every day.

As of today, the protests continue in Taksim and in different parts of the country.

A protest started by a very small group of people, mostly university students, to protect one of the last green areas in downtown Istanbul has turned into a giant public protest against the government.

(Montage credit: Metehan Sonbahar)

Some international media have portrayed events here as a “Turkish Spring”. That is a misrepresentation.

I believe what is happing now in Turkey is not different from the Occupy protests in London last year, or in the US in 2011. Similar things continue in Spain, Greece and elsewhere. Such demonstrations will always happen in democratic regimes.

The lesson is, there are better ways of going about redevelopment. The authorities could have organised a competition for ideas to be voted on by the public. This was not done. There was the name of the project only, but not the details.

Gezi Park is a popular and rare oasis of green in Istanbul, but the government chose to disregard community concerns over traffic, the environment, and standards of living by pushing forward “redevelopment†plans by decree.

This was the breaking point.

Metehan Sonbahar is senior construction consultant at Akinci Law Office in Istanbul