If we knew exactly how well a building performed, from the cutting of the ribbon to the swing of the wrecking ball, we could accurately charge for its use by the hour. Very smart buildings, made possible by pervasive data and real-time analytics, may change the property business model, and render traditional contracting obsolete.

Two megatrends have transformed the business world in the past ten years. One is the triumph of services over products, which has altered the business models of sectors ranging from music to airlines.

In music, downloads and streaming services have laid waste to the market for physical media such as compact discs (remember those?), while in air travel, engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce no longer sells engines, but flying time.

We see it in the automotive industry, where car makers have begun wrapping their heads around how to sell “mobility as a service” through various car-sharing applications. It’s a concept deemed important enough to have its own acronym: MaaS. And for some time now software giants such as Adobe and Microsoft have been leasing software rather than flogging boxed discs. Say hello to “SaaS”.

One example of where the industry could go is the Rolls-Royce model, where rather than buying an engine, you buy air miles. Maybe in the future you buy a building based on its meeting certain design criteria for a certain number of hours– Andrew Duncan, BIM manager at Arup

A second megatrend is the digitisation of commercial transactions. The days of physically entering shops to buy objects have not gone, of course, but increasingly consumers have the alternative of ordering on their PCs or smartphones.

In limited ways these trends have appeared in the world of property and construction. The idea of buying accommodation services rather than a building was at the heart of the UK private finance initiative (PFI) in the 1990s, where it was used mainly to build hospitals that the state couldn’t afford, and has since mutated into a range of public-private partnership (PPP) arrangements from toll roads and prisons to waste disposal and electricity generation.

Meanwhile the use of digital construction, in the form of the building information model (BIM), is creating new kinds of role and new working practices as it slowly seeps through the global industry.

BIM has not yet affected the way buildings are bought and sold but, as with DVDs and automobiles, it may be about to, and in so doing it has the potential to change the industry beyond recognition.

BIM isn’t just a model, you know

To date, construction has understood a BIM to be a multi-dimensional design tool that helps with clash detection and works scheduling. But a number of firms are now realising that it’s actually much more.

Andrew Duncan, a BIM manager at Arup who has been involved in thinking through the future of digital modelling, and who recently helped design a BIM that modelled a 170m-high human building, says: “The way that I like to think of BIM is as a database that happens to be able to articulate itself in 3D, but it can also articulate itself through a number of other mediums such as drawing or schedules or reports and so on.”

The client has invested a lot of money in an FM system and might be using it on more than one building, so they’re not going to say ‘let’s scrap our FM system and switch to BIM– Allan Hunt, director at AHR Building Consultancy

The potential for a BIM to enjoy an active life after a building has been completed depends on this ability to transmute information into different forms. The problem up to now is that building owners already have facilities management and building management software to run their systems.

Allan Hunt, a director at AHR Building Consultancy, one of the pioneers of information modelling in the UK, says that large buildings already have FM systems that are incompatible with the BIM. “The client has invested a lot of money in an FM system and might be using it on more than one building, so they’re not going to say ‘let’s scrap our FM system and switch to BIM’.”

However, although this has delayed the take-up of BIMs as database, other factors may promote it in the future. One is that organisations that own or run buildings will eventually have to renew their software, and another is that, when they do, the building model may have acquired a whole range of new capabilities, such as the ability to continuously update the information in its database, and link it to other systems.

Real-time analytics

A building information database linked to real time sensors can log any number of metrics to determine how well a building is performing against what the architects and engineers predicted. Now the property industry is, as Duncan says, “horrendously bad” at collecting and using operational information.

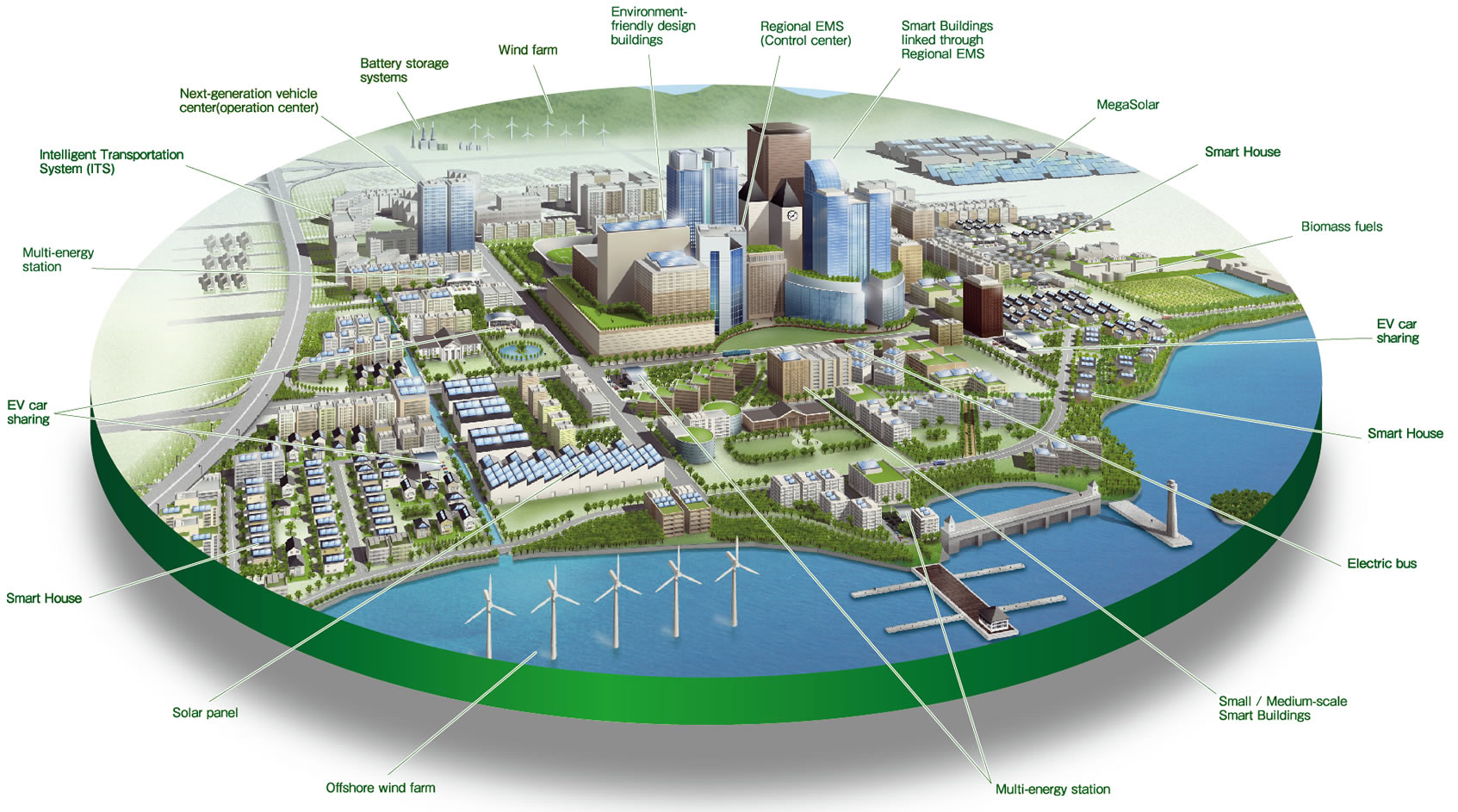

How will smart buildings fit in to the evolving eco-system of the smart city? (Image courtesy of the District of the Future Project)

Such a database could also determine the quality of service the building user is receiving. It is common for PPP contracts to specify service levels and link them to payment, although accurate assessments of service quality are difficult to achieve. One example from the UK was the PFI hospital where the contractor running it was rewarded or penalised depending on how quickly its staff turned up to fix a building problem, regardless of whether they actually fixed it. In the future, the possibility exists to create a full, transparent and objective log of how a building performs, to ground payment in reality. Take one more step – digitise the transaction – and the way opens for selling “BaaS”, or buildings as a service.

“One example of where the industry could go is the Rolls-Royce model, where rather than buying an engine, you buy air miles,” says Duncan. “Maybe in the future you buy a building based on its meeting certain design criteria for a certain number of hours. Of course Rolls-Royce monitors the engine in flight and if anything goes wrong, it’s there to service it, and if they need to swap an entire engine they swap it, because it’s still its engine.”

Every country uses its own terms and units, and there are few international standards that would make digital construction interoperable

This model is not that futuristic. In process industries like mining and smelting it is standard for the entire operation to be run remotely from a control room that may be on another continent, using more computing power than you might find in the headquarters of a multinational bank. In contrast, the property sector has shown a relative lack of interest in real-time analytics. We have fire systems, security systems and, lately, systems for monitoring energy use, but they tend to be in silos. We haven’t joined it all up, maybe because there hasn’t been anything to join it all up to. That is changing. Â

Open-source buildingsÂ

There are already signs of a shift. Hunt gives the example of IBM’s Maximo asset management tool, which it developed with Autodesk. It offers “asset lifecycle and maintenance management”. Hunt says some major airports are using it, and it is influencing other FM systems.

But a serious impediment to the growth of digital construction is the lack of common standards for the data that goes into the BIM. Every country uses its own terms and units, and there are few international standards that would make digital construction interoperable.

Duncan says: “In order to achieve real-time databases what we need is structured, consistent data, because if we don’t have sensors linked with the correct protocols back to the databases that hold that information and replay it to people who are able to make decisions regarding the effect that information is having on future designs or current occupants then we’ll get stuck in data cul-de-sacs.”

This problem of determining how to create consistent data and universal protocols is being tackled by BuildingSMART (the organisation formerly known as the Alliance for Interoperability). It is working on the development of OpenBIM – an international language that would allow databases and the system that link to them to be universally understandable. Its major achievement so far has been the development of industry foundation classes, or IFCs, as an open way of expressing data, but there is, as Duncan says, still a long way to go before different buildings can be measured with the same ruler.

Goodbye, contractors?

OpenBIM is an international language that would allow databases and the system that link to them to be universally understandable

If all this comes to pass it holds out a number of interesting possibilities. One is that contractors no longer put up buildings for a negotiated sum and walk away, but instead own and manage what they build for a long time, possibly for the duration of the building’s life, including its recycling. That would lead to a much more thoroughgoing use of whole lifecycle costing.

Another possibility is the creation of building performance benchmarks in a way that would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. If this happens, it will make the whole industry much more transparent to customers and regulators. Perhaps entire districts could be automated from a single control room to optimise energy use and make sure everyone has a parking space.

A third possibility is the bringing into being of a whole new stream of Big Data. All that information about the building’s operation will be swirling around the cloud, available for purposes we can only guess at. A team within Arup is working on how users in a building can manipulate their environment using smartphones linked to a number of open-source protocols, but other app designers will doubtlessly be able to do other things, possibly involving other evolving technologies, such as self-driving cars and solar batteries and (who knows?) 3D printing and drones. Finally, there is the equally open question of how building information databases will fit into the smart city as it evolves in the next ten years.

The possibilities are endless.

Top image: A modern industrial control room. Could buildings soon be run from places like these? (Image courtesy of ABB)

Comments

Comments are closed.

Even a brand new building very soon becomes outdated and has constantly to be upgraded to conform with and to accommodate ever newer and more efficient services and even aesthetic trends! So who better to make such adaptations than those who designed and built it in the first place?