By building just five dams, the “Atlantropa” scheme would have fused Europe to Africa, creating power and vast swathes of fertile farmland…

We’re quite used to the idea of mega projects – bold interferences with the Earth’s natural systems done in the service of a perceived human good, such as China’s Three Gorges Dam, or Ethiopia’s scheme to dam the Blue Nile.

But what about “ultra projects”, those really astounding and even horrifying visions to change the face of the earth for mankind’s benefit? We don’t think like that anymore, do we?

Well, not so long ago, influential people did.

An intriguing example is the idea proposed by the Bavarian architect Herman Sörgel in 1927 concerning the creation of an entire continent, which he called “Atlantropa”. This plan, which required a series of astonishing engineering feats, surely has a claim to be the most visionary construction programme in history.

What Sörgel proposed was first of all to build a 35km-long dam across the straits of Gibraltar to prevent the Atlantic from replenishing the Mediterranean. Every year about 4,000 cubic kilometres of water are drawn through the straits, a rate equal to about 10 Niagara Falls. Without that inflow, the level of the Mediterranean would fall about 1.7m a year as a result of evaporation. After about a century it would be 200m lower, at which point it might stabilize.Â

And why do this? Well, the retreat of the sea would, it was thought, create about 600,000 square kilometres of virgin land – a repeat of the Dutch Zuiderzee works, which began in 1927 – but on a massively greater scale. The biggest winners would be Italy, which would become a bulge rather than a boot, and would gain a vast plain of agricultural land.

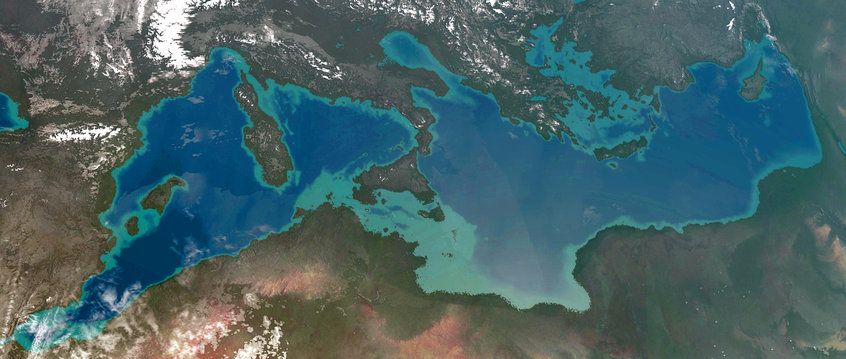

Sicily would become part of the Italian mainland, Sardinia and Corsica would fuse, as would Majorca and Minorca, the Peloponnese would become one with northern Greece and both would greatly expand in size. In the Black Sea, which would become the Black Lake, the modern dispute over ownership of the Crimea would not arise, as the peninsula become contiguous with the southern Ukraine.

Look familiar? It’s Mediterranean, once evaporation has lowered sea level by 200m (Wikimedia Commons)

Meanwhile, the dam itself would become a hydroelectric power plant that would be capable of supplying about half of this expanded Europe’s power needs. The rest of the juice would come from dams across the across the Dardanelles, which would cut the Mediterranean off from the Black Sea, and a fourth across the Suez Canal to partition off the Red Sea. Â

Powering Europe

Once the water level reached the target depth, the culmination of this part of the scheme would be a huge fourth dam, built across the across the newly created Straits of Tunisia. Altogether, he calculated that 365GW of electricity would be provided, roughly equal to the modern installed capacity of Germany, France and the UK, and more than enough to power Europe in the 1930s.

Northern Africa would do less well, but Sörgel had big plans for that continent as well. Firstly, the Sicily-Tunisia dam would double as a rail and road causeway between Africa and Europe.Â

And why would such a link would be necessary? This was the second part of Sörgel’s plan: the greening of the Sahara.

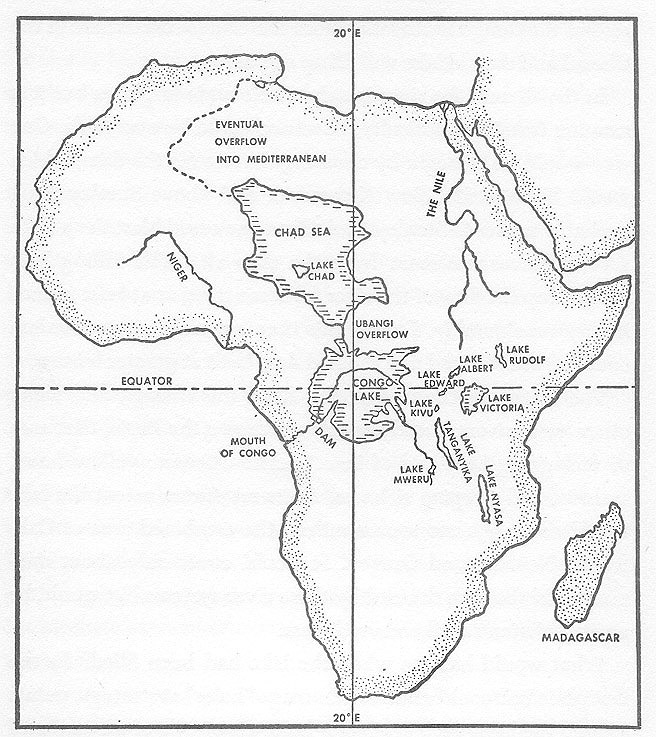

He planned to accomplish this second engineering miracle with a fifth dam, this time across the Congo river where it enters a series of gorges after its confluence with the Kwa river. The aim here was not just hydro power, as it is with the real life Grand Inga Dam, which is about 300km downstream from the Kwa, but rather to replace what was then the Belgian Congo and French Cameroun with what would briefly be the biggest lake in the world, about equal to the combined size of California, Nevada and Oregon.

This would eventually reverse the flow of the Shari river and refill Lake Chad, which would overtake Lake Congo as the world’s biggest lake, and would create a navigable river that would flow north into Algeria and the Mediterranean – thereby connecting the two schemes and providing the reservoir of fresh water necessary to begin the irrigation of the Sahara. Â

A big hit in Weimar

This was more than mere whimsy. Sörgel really believed that it could be done, and it’s fair to say that he was obsessed by this idea. Because he had the financial support of his wife Irene, who was a successful art dealer, and had himself begun the successful architecture magazine, Baukunst, he was able to work continuously on his plans until his death in 1952 at the age of 67. He wrote four books and more than 1,000 articles and papers to popularise the idea.

The reshaping of Africa to make it more useful to European involved flooding vast areas to make them navigable by boat. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

When Sörgel had his big idea, he was living in the bohemian Schwabing quarter of Munich, where, in the words of Wolfgang Voigt, the curator the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt, visionaries conceived schemes to save the world every Thursday.Â

By all accounts, Sörgel was an attractive and charismatic figure, and he managed to distinguish his scheme from the competition and actually succeeded in putting it before the German public and the Weimar government, where it won considerable support.Â

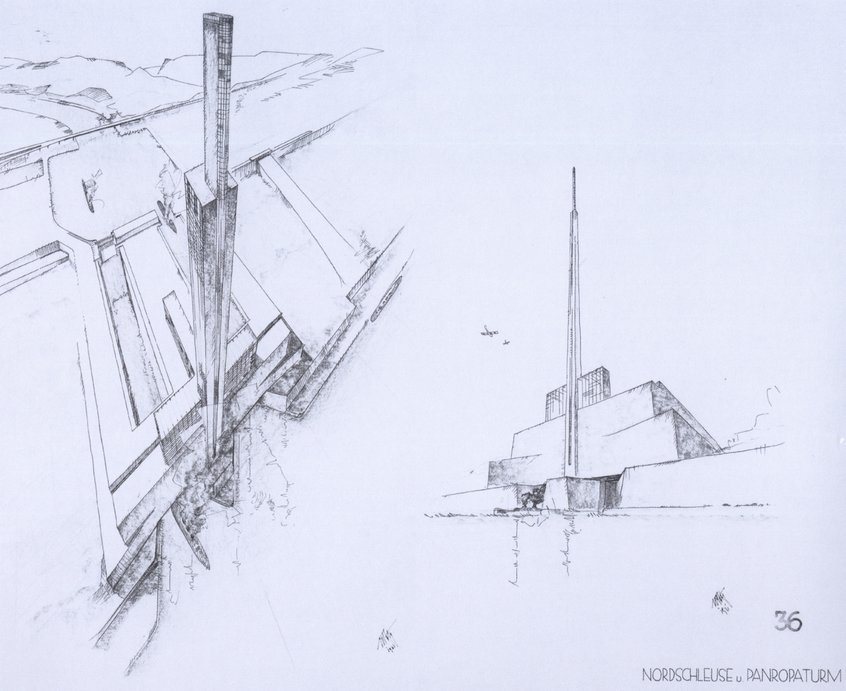

Other architects shared his belief. Peter Behrens, one of the founding fathers of the modernist movement, designed skyscrapers that would stand above the canal locks of the Gibraltar dam (pictured). The architect Erich Mendelsohn offered to work on the newly emerged coast of Palestine.

Others ridiculed the idea, of course, largely because of the unlikelihood that it could win consent from all the countries it would affect, and from the vast numbers of people living along the present coastline of the Mediterranean. The fishing industry was another problem: evaporation would eventually turn the Mediterranean big, dead salt lake.

One group who objected to the purpose of Atlantropa were the National Socialists. Their hostility killed any idea that the scheme might be implemented in the immediate future. In 1942, Sörgel was forbidden from publishing any more books.Â

Beautiful, or evil?

Looked at purely as an engineering solution, Atlantropa has a number of beautiful features. One is the elegance of the concept: a transformative feat of geoengineering is accomplished with no more than five concrete structures. Food can be provided for 150 million people, and electricity for 200 million. And as it would take one or two centuries to complete the scheme, it would also provide permanent full employment.

But for Sörgel, these gains were not the ultimate point of the project. The real aim was to bring Europe together after the trauma of the Great War, stave off the threat of another and allow the continent to maintain its independence before the rising powers of Soviet Russia and the United States.

To do this, he thought, Europe had to use Africa – which, with the solitary exception of Abyssinia, it had already taken possession of. Africa would, in Sörgel’s words, be turned into a “territory actually useful to Europe”.

In this way a feat of physical engineering would lead to an even more remarkable feat of social and geopolitical engineering. It was precisely his idea that Europe could solve its problems and assert itself in a peaceful way that earned him the scorn of the Nazis.

Peter Behrens’ drawings for a skyscraper beside the Gibraltar dam (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Today, such a scheme as Atlantropa would seem ridiculous and abhorrent. Erasing entire countries and displacing populations to make Africa “useful” to Europeans? Killing the Mediterranean and Black seas, and obliterating entire river systems?Â

After the fall of the Third Reich, the idea of a new continent of Atlantropa was briefly reprised, but by that time the problem of endless cheap energy had already been “solved” by other means: the nuclear power station.

It’s worth remembering Atlantropa because it reminds us of the planetary hubris humankind is capable of, a hubris that had its heyday with the murderous, man-made catastrophes of the mid-20th century.

But did the “ultra project” really die when Sörgel did, in 1952?Â

Flooding the desert

In fact, his Atlantropa vision lived on in little ways. In the American science fiction writer Philip K Dick’s alternative history novel “The Man in the High Castle”, published in 1962, the victorious Nazis change their mind and drain the Mediterranean as part of “Operation Farmland”.Â

In Gene Roddenberry’s book of the first “Star Trek” movie, published in 1979, Captain Kirk stands on the Gibraltar dam.

And in a German school examination paper in 2003, candidates were required to calculate how much power could be produced by such a dam. Of course, there is no saying that the notion of Atlantropa is gone forever. Forever is a long time, and the future is another country where they will doubtlessly do things differently.Â

Meanwhile, a variant of one part of Sörgel’s plan – the flooding of Egypt’s Qattara depression – has kept engineers busy in more recent years.

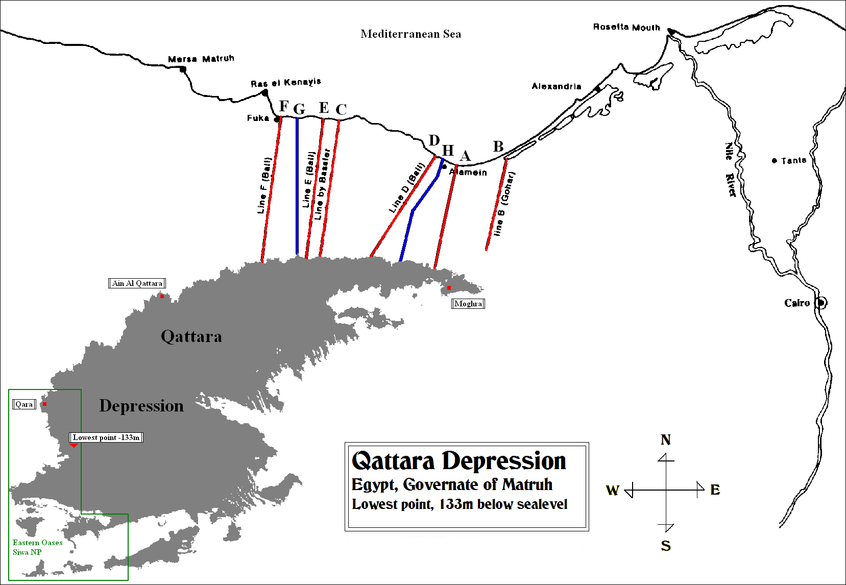

The idea has been around for a hundred years or so. It would involve digging a 65km canal or tunnel between the Mediterranean Sea and the second lowest place in Africa, a 19,000 square kilometre expanse of salt marsh in what is known as the Libyan Desert, which dips in places to 133m below sea level.Â

The depression would fill, but evaporation would pull in a flow equal to about half of Niagara Falls – enough to generate up to 2 GW of power.

A map of the proposed tunnel or canal routes between the Mediterranean and the Qattara (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

That is not enough to solve Egypt’s electricity problems, but given that it cost about $1bn to create a gigawatt of installed capacity now, and the lack of other hydroelectric options, it might be worth a second glance.

The subsidiary benefit, of course, would be to create a tourist destination in the middle of the Libyan desert.

The main proponent of this scheme was, rather surprisingly, the CIA, which advanced it in the 1950s as a way of distracting President Nasser from political adventures. In the 1960s, a German hydraulic expert from the Technischen Hochschule Darmstadt called Friedrich Bassler led an international Board of Advisers that was responsible for planning and financing the project.Â

After much work on the feasibility of the scheme, the Egyptian government of Anwar Sadat decided in 1975 to ask Bassler and a consortium known as Joint Venture Qattara to conduct another feasibility study of the project. The main difficulty was the cost of digging the canal. Bassler’s solution to that problem was to do it with 213 nuclear devices, at which point the Egyptians thanked the professor and said they’d get in touch. Nothing has been actively proposed since, although the project is still at the back of many engineers’ minds.Â

Great Green Wall

Perhaps the closest contender as an “ultra project” nowadays is the green wall idea, a far more benign and conservative approach to north Africa.Â

This envisages the planting of a 6,500km-long, 15km-wide wall of trees from Dakar in Senegal to Djibouti on the Red Sea Coast. The aim is not to return the Sahara to the lush pastureland it was a few thousand years ago, but rather to halt the process of desertification that is nibbling away at the upper edges of sub-Saharan Africa. This scheme was conceived by the African Union, has the backing of the 11 states that formed the Panafrican Agency of the Great Green Wall.

Work on that project is going ahead, with funding from the EU among other sources, although in its present form it is a “mosaic” of measures to improve the water resilience of farmers in marginal areas, rather than a feature that would have been visible from space.