While the developed world continues to stagnate, Africa has seen an enviable average growth of more than 5% over the past decade, leading the World Bank to refer to an “African economic renaissance”.

GCR predicts that in the next 10 years, companies who sell construction services internationally will ignore Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, at their peril.

In the first of a series of reports on Africa’s infrastructure needs and opportunities, Rod Sweet looks at roads.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the average speed of overland travel has been estimated to be somewhere between six and 11 kilometres per hour, according to statistics published by the African Development Bank.

That’s about what a horse and cart can do on a bumpy, unpaved road.

Africa’s chronic underinvestment in transport infrastructure has led to widespread dilapidation.

And dilapidated infrastructure means astronomical transport costs, which in turn kills economic growth.

The epitome of this dynamic is landlocked Chad, where the cost of getting a single shipping container into the country stands at $8,525, compared to the $875 it costs in landlocked Hungary, according to the World Bank.

A new report from the World Economic Forum (WEF), Africa Competitiveness Report 2013, brings the issue into stark focus.

It says that even between 2005 and 2012, a period of growth and renewed focus on development, African countries invested 15% to 25% of their GDP in transport infrastructure, on average, while India and China were busy spending around 32% and 42%, respectively, in the same period.

Roads are the predominant mode of transport in Africa, and they’re terrible.

In Tanzania, the WEF report says, 92% of the road network is unpaved, and liable to be unusable in the rainy season.

Only 24% of its population lives within 2km of an all-weather road – not bad compared to Zambia, where the figure is 17%, and Ethiopia, where it’s 10.5%.

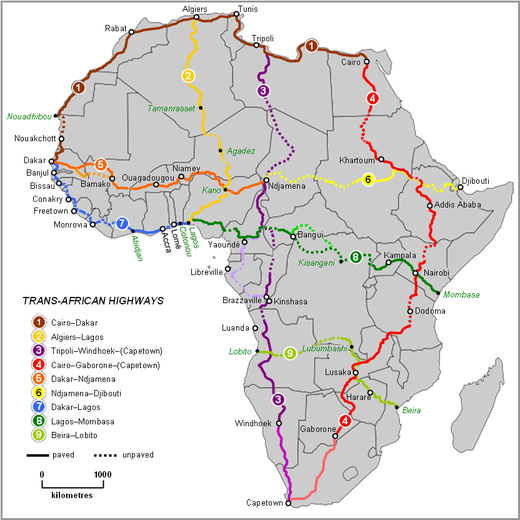

Visionary scheme of the Trans African Highway. (Credit: Rex Parry)

Where there are paved or durably built dirt roads, they’re not given a chance to live out their designed lives because people, desperate to get things moving, overload vehicles.

In Uganda, overload rates are close to 55%, the WEF report finds.

Meagre maintenance budgets cannot keep pace with the rapid degradation.

Road fatalities and chronic congestion are two further elements of the un-virtuous circle that cause misery and eat measurably into the region’s economic performance, the WEF report says.

Missing links

The scale of the challenge is huge, and so too are some of the visions for improvement.

Most ambitious is the Trans-Africa Highway (TAH).

It comprises nine interlinked highways criss-crossing the continent and spanning a total length of 56,683km.

But many links remain missing, and even paved sections are falling into disrepair.

Other planned or ongoing regional projects include the Abidjan-Ouagadougou-Bamako Transport corridor, connecting Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Mali.

Such plans face many obstacles, however.

At the national level, legislative and financial issues need to be addressed. In Uganda, for instance, although a PPP policy is in place the relevant law has not yet been enacted.

With the exception of a few countries, including Senegal and South Africa, toll roads are not yet completed.

More importantly, since transport corridors must cross borders if they are to make an economic difference, technical, financial and political cooperation between countries must improve.

The challenge may be huge, but an optimistic reading of the situation suggests that the opportunity may be huge, as well.

Investment into Africa, particularly from China, has soared. Peace on the continent, according to some observers, is spreading.

In such circumstances, it’s hard to see how Africa’s age of the horse and cart can persist forever.