Japanese engineers are preparing to stick one of the world’s biggest wind turbines onto a large platform that will generate enough electricity for nearly six thousand homes while it floats off the coast near Fukushima.

The experiment, a joint project of 10 of the country’s top engineering firms and Tokyo University, is the latest bid to solve the island nation’s power problems as it struggles to deal with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of March 2011.

Sponsored by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the scheme will probe the possibilities of opening up Japan’s vast territorial waters to wind-energy harvesting, and of commercialising the technology for export around the world.

Japan needs floating wind farms because the seabed off its coasts are too steep to build on: in the north east, especially, the ocean floor plunges rapidly into the Japan Trench, which has depths reaching 9,000 metres.

The government hatched the plan in August 2011, just six months after the magnitude 9.0 TÅhoku earthquake triggered the tsunami that killed approximately 16,000 Japanese people and wrecked the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station, throwing into turmoil the future of country’s nuclear power industry on which it depends.

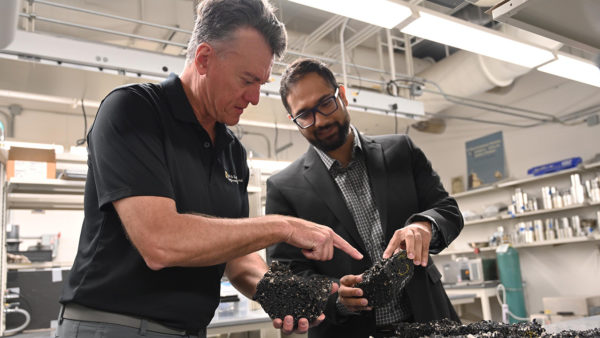

One we built earlier: a smaller, 2MW turbine was fixed to the floating platform for trials in 2013 (Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium)

It became something of a personal mission for one of the project’s leaders, Tomofumi Fukuda, the domestic power general manager for Marubeni Corporation, the conglomerate tasked with pulling the project together. He had returned to Japan from several years in the West Indies only a month after the tsunami.

“As soon as I heard about the Fukushima Recovery/Floating Offshore Wind Farm Experimental Project from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in August, 2011, I was instantly convinced that this should be Marubeni’s project,” he writes on the company’s project page.

“The driving force for me,” he adds, “is a big dream to make Japan a next-generation energy leader. In Japan, the amount of renewable energy is only 1% of the total energy. I feel that only floating-type offshore wind generation can raise this up to 10% or 20%.”

The scheme relies on the latest marine engineering techniques used in deepwater offshore oil and gas production. A 200-m-high, 7MW turbine will sit atop a semi-submersible (half-sunk) tri-pod platform (pictured above) made up of three large hollow cylinders, also known as “spars”.

Floating next to the tri-pod will be another semi-submersible, a single spar, housing the substation. Its job will be to boost the voltage from the turbines from 22kV to 66kV for transmission via cables to the onshore substation 23km away.

The floating spars will be equipped with the latest technology to reduce pitching and rolling in heavy seas, and will be anchored to the sea floor with an “ultra-huge” chain nearly a kilometre in length. Each link of the chain weighs 200kg.

The project consortium (members are listed below) has already tested a smaller floating version. In the summer of 2013 they put a 2MW turbine on the tri-pod platform, and it worked.

A 2MW turbine, says Marubeni, can produce six million kilowatts per year, enough to power 1,700 households in Japan. A 7MW turbines could conceivably power three and a half times that number – 5,950 households.

Progress

Now, the tripod and single spar platforms are making the long journey up Japan’s east coast from the the Mitsubishi shipyard at Nagasaki to the Port of Onahama, just north of the coastal location of the Fukushima Daiichi power station, according to a progress report issued on 30 October by the consortium.

At Onahama, between now and January 2015, a massive crane will be built to hoist the turbine onto the tri-pod spar. At 200m in height, with blade diameters of 160m, this turbine is among the biggest in the world today.

To facilitate the lift, the ground had to be strengthened and an underwater mound built at the Onahama port.

Meanwhile, anchors, the “ultra-huge” chains and transmission cables have been laid offshore at the testing site.

The consortium hopes that in February 2015, weather permitting, one of the world’s first, and certainly the biggest, floating windfarm can be towed into place and switched on.

• Members of the Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium include Marubeni Corporation (project integrator), University of Tokyo, Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Japan Marine United Corporation, Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding, Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation, Hitachi, Furukawa Electric, Shimizu Corporation, and Mizuho Information & Research Institute.

Main photograph: The tri-pod spar platform leaving the shipyard in Nagasaki to make its way to Onahama (Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium)