More than 2.3 billion people, almost a third of the world’s population, is unable to drink water from a tap without concern for their health. Of those, 844 million do not have access to any potable drinking water at all. Some 4.7 billion people do not have access to toilets connected with modern sewerage and waste processing.

And the prospects for future improvement are in doubt as economic development struggles against the forces of environmental degradation, climate change, population growth and urbanisation.

The result is that cholera and dysentery kill some 780,000 people a year, far more than wars, earthquakes and epidemics.

This is the sombre assessment of the 2019 UN World Water Development Report, Leaving No One Behind, published this week by Unesco to coincide with World Water Day on 22 March.

The statistical picture illustrates the failure of global economic development to provide basic water and sanitation across large areas of Africa and Asia.

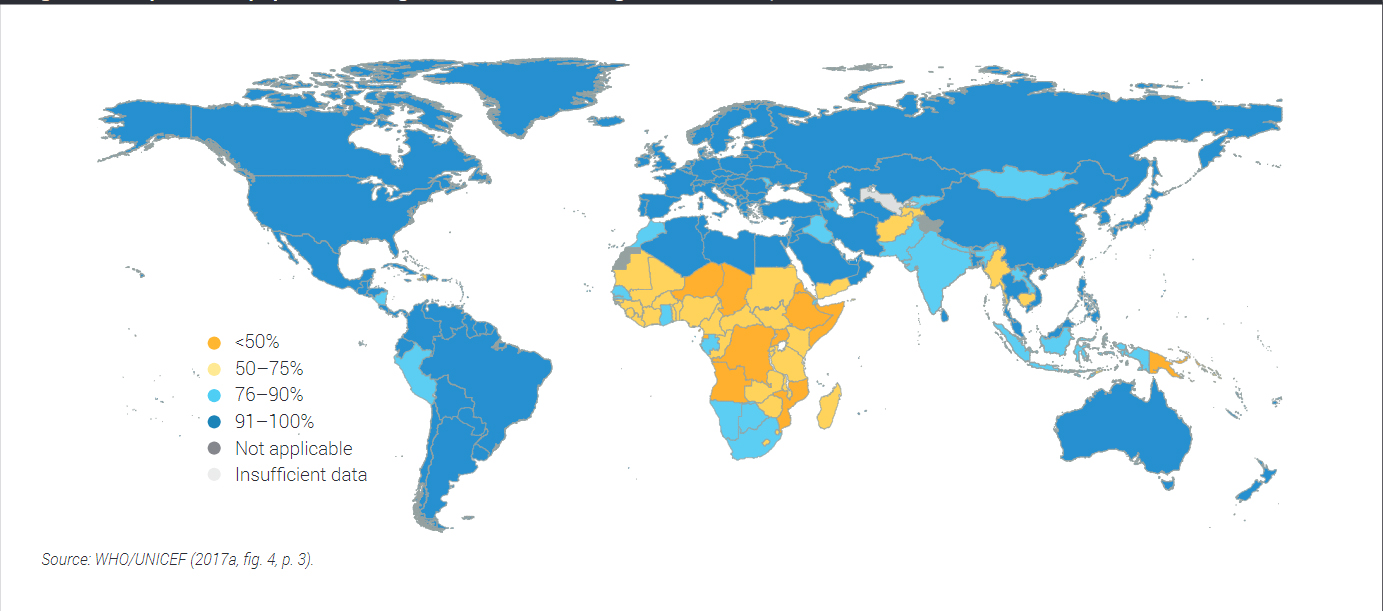

The proportion of the populations with basic drinking water in 2015

At the same time, the report says, progress has been made: more than a billion more people have gained access to a water point connected to a pipeline between 2000 and 2015, even though that water may not be from an “improved source”.

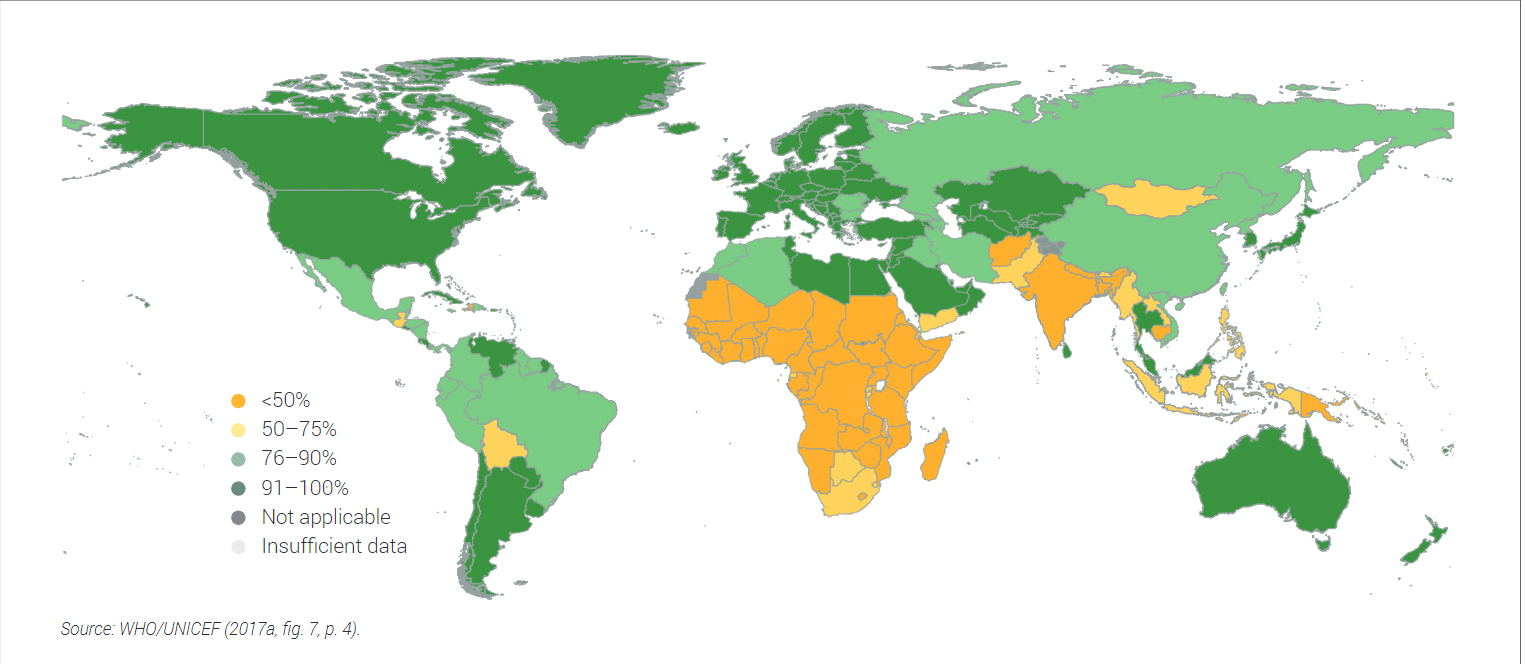

On the sanitation side, 68% of the population uses at least one basic service, compared with 59% 15 years ago.

However, in 2015, six out of 10 people did not have access to toilets that were not shared with neighbours and whose output was subject to some kind of treatment to make it safe.

The report notes that water use has been increasing worldwide by about 1% a year since the 1980s, and is expected to continue at a similar rate until 2050, accounting for an increase of up to 30% above the current level of use.

Over 2 billion people live in countries experiencing high water stress, and about 4 billion people experience severe water scarcity during at least one month of the year. Stress levels will continue to increase as demand for water grows and the effects of climate change intensify.

Water stress is most severe in the global South, where cities such as Saana, the capital of Yemen, is facing a complete exhaustion of its water resources.

The proportion of the populations with basic sanitation in 2015

However, it is also threatening more developed countries. Researchers at UAE University at Al Ain warned in 2015 that a combination of rapid population growth and wasteful practices could drain the region’s aquifers by 2030.

Sir James Bevan, head of the UK Environment Agency, told the Waterwise Conference in London this week that in around 20 to 25 years, England would reach the “jaws of death”, where, unless action is taken, there will not be enough water to supply the country’s needs.

The UN report concludes that improving the distribution of water and sanitation is, at root, a political problem that requires more democracy.

The report called it a “renegotiation of power relations at all levels” to allow those left behind “appropriate representation in political and other decision-making processes”.

It also requires good governance, better regulatory and legal frameworks, and “fair and effective management of financial resources”.

The report adds that this will require a change in “attitudes and norms within water institutions” and a recognition of states as the “primary duty-bearers for ensuring that the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation are realised for all”.

Top image: A well in a village in Faryab Province, Afghanistan (Didier Berghe/Public domain)

Further reading:

Comments

Comments are closed.

How bad does it have to get before people will wake up

I agree with Sheila Anderson!