First conceived in 1992, the world’s biggest museum is expected to open this year. GCR’s David Rogers got the chance to take a look.

The scale of Grand Egyptian Museum’s atrium seems to take its cue from the 11m-high statue of a smiling Rameses II that strides to meet visitors as they enter.

It’s immense. The horizontal sightlines stretch some 800m, and the roof’s cross-hatched brise-soleil is more than 38m above the visitor’s head.

The scale of the physical space – it’s the world’s biggest museum – allows it to maintain a sense of cool spaciousness.

The building covers 90,000 sq m, which is 17,000 more than the Louvre, and it will curate more than 100,000 artefacts of which 18,000 will be on display at any one time.

This contrasts sharply with the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, which crams 120,000 items into a 13,600 sq m mansion built in 1901.

Rather than aiming for comprehensiveness, the new prime repository is selective about what it shows. It gives the pieces room to breathe and weaves stories around them.

The real test will come later this year, when the museum officially opens and the crowds arrive. On average, 38,000 people a day visit the Giza pyramid complex, and the museum next door will be a necessary addition to their itinerary.

At present, only a few private tour groups are coming to look at the atrium. It’s a good indication of the museum’s approach to design.

The triangle motif is prominent, particularly on the limestone-panel facades, and the structure is everywhere on the slant. It takes some searching to find a 90° angle.

The colour palette is restricted to shades of brown and grey depending on the stone used. This varies from amber onyx pyramids at the entrance to Egyptian granite and the Trieste limestone used to fashion Rameses and the Giza pyramids. Much the same colour scheme, complete with decorative cartouches, is evident at the New Administrative Capital buildings, suggesting its adaptation as a kind of national livery.

What’s inside

The size of the museum reflects the scale of the task it performs. It can be difficult for anyone coming from a more youthful culture to appreciate just how far into the past Egyptian history extends.

The neolithic cultures that had been in the Nile Valley for around six centuries cohered into the first dynasties of the Old Kingdom around 3,150 BC. Thereafter, an Egyptian civilisation arose with a distinctive artistic style, written language, and social organisation. This remained recognisable over a period of about 4,000 years, until a definitive break came with the Arab conquest of 641 AD.

What this means is that when Rameses II fought the battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC – the event that his statue celebrates – the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom was about as distant to him as the last dynasty of the New Kingdom is to us now.

That’s the span of time the museum was built to cover.

A second consideration is that the arid Egyptian climate preserved more or less everything, including papyrus and wooden objects that only survive in deserts. In any case, Egyptians used stone for their important buildings, and they covered it with information, all of which became legible with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799.

As a result, the sheer quantity of material gathered over that time, and the amount that it tells us, is astonishing. How does the museum make it intelligible for the visitor?

The principles behind the museum’s internal layout are explained by Mennatallah Heikal, design coordinator for project manager Hill International. The galleries, she says, are divided into historical epochs: pre-dynastic, Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom, followed by the Greco-Roman period.

Within the galleries, the artefacts are arranged into thematic streams, such as society, kingship, and religion.

“If I want to concentrate on one aspect of life, say society and how it evolved, I would go in one direction,” she said. “If I want to study one era, I go in the other direction, so it’s a matrix.”

She adds that the division of themes follows the Egyptian association of the east where the sun rises with life, and the west with death.

For example, the urban centre of Thebes, which arose in the Middle Kingdom, had the temple complex of Karnak on the east bank of the Nile and the necropolis, including the Valley of the Kings, on the west. So in the chronological galleries, subjects dealing with funeral procedures and the afterlife are on the western side and those dealing with living society on the east.

Her job is to work with the Ministry of Antiquities to decide on the correct place for every artefact in the matrix. “We advise them on what would work well with the building and what wouldn’t, and whether it should be on the east or west.”

Set pieces

As well as the chronological galleries, the museum has a number of spectacular set pieces. First among them are the two Tutankhamen exhibition halls, which will gather together some 5,000 objects from the tomb and display them together for the first time.

Perihan Elwy, Hill’s vice president for Egypt, says this area will tell the story of the pharaoh’s brief but eventful life – he died in his late teens after a 10-year reign – as well as the story of archaeologist Howard Carter’s discovery of his miraculously intact tomb in 1922.

“We will explain how his lifestyle was, his funeral, his family and his relations with them and then his life after death,” she says. “Some of the objects were in the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square and some were never displayed before. Some were in a bad shape and needed a lot of restoration.”

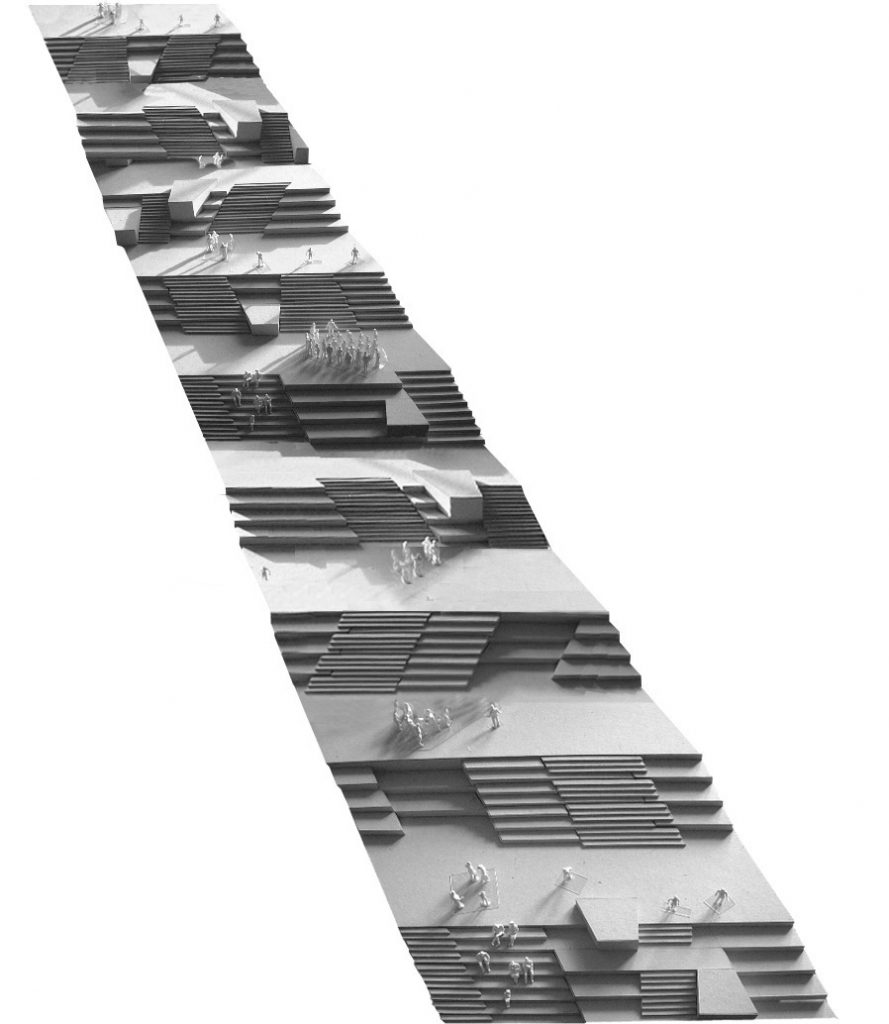

Another set piece is the huge staircase that leads from the atrium to an upper terrace containing an intricate model of the museum. This dramatic space has been used to display some 88 large pieces, such as sarcophaguses and sphinxes.

Most are made from grey granite and limestone that harmonises with the polished limestone stairs. Encountering these objects in that setting creates an air of informality, as though you were meeting them by chance on your way to somewhere else.

Huibert Vos, Hill International’s project director for the museum, corrects that impression. They were a huge problem to move and position roughly in the right place. The final layout is still being worked out, and cameras are forbidden.

The main issue, he says, is that there were height restrictions. “You can’t come with a big crane for a 23-tonne object so we had to make specific transport arrangements. We had to install a monorail on the side of the staircase, like a funicular railway, then pull them sideways with a little gantry crane.”

As to when the final dispositions will be made, Huibert says that is out of the project team’s hands. Officially the main building is 99% complete, but the last word on the arrangement of the exhibits belongs with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

“We’ll be ready with documentation and final account before the project opens,” he said. “The building is finished the security systems are working, everything is already functioning and it’s tested.”

A third is three Giza pyramids, visible from the museum, and connected to it by a 2km-long, 500m wide passage. This link is symbolic as well as practical, since it’s a physical connection between the ancient and the modern.

The passage will have green landscaping, and will be part of a wider development of the Giza area, with spurs to the shooting club and stables for the horse riders who tend to gallop around the plateau.

Timeline

If the museum does indeed open this year before December’s presidential election, it will be the end of an epic construction effort.

The project was conceived in 1992, when then president Hosni Mubarak issued a presidential decree setting aside around 50ha of the Giza plateau for a museum.

The idea took definite shape six years later when the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) agreed a $300m loan.

But it wasn’t until 2002 that the ceremonial cornerstone was laid, itself a premature act since no design had been chosen.

Unesco launched an international competition later that year, drawing concept designs from 1,557 architects in 83 countries. It was billed as the biggest design competition ever held.

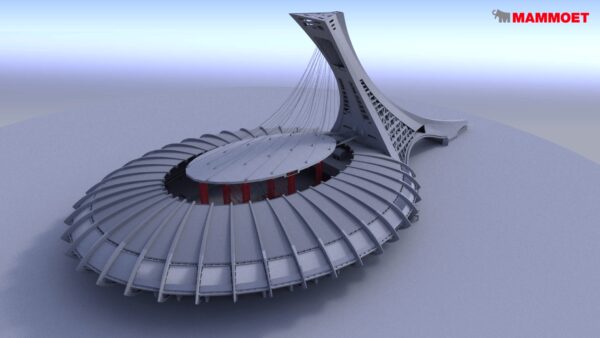

The result was a shock. The winning design had been entered by Heneghan Peng, a virtually unknown practice founded in New York in 1999, now based in Dublin. It resembled a half-open fan laid on the desert floor and widening towards the pyramids, about 2km to the southeast.

The core of the construction team was made up of three joint ventures. The project management was entrusted to Hill International, a US company with a strong track record in the Middle East and North Africa, in conjunction with Egyptian multidisciplinary consultant EHAF.

The engineering design was taken on by UK firms Arup and Buro Happold, and the construction package went to Egyptian contractor Orascom and Belgium’s Besix.

A difficult birth

Between 2005 and 2010, the site was surveyed and prepared, and a high-tech conservation centre was built, all paid for by the Egyptian government.

Then in 2011 the country experienced a popular upheaval, followed by an Islamic government and an abrupt reversion to the status quo in 2014.

Amid political and economic instability the project began to drift such that by 2016, when the country had stabilised, only 20% of the work had been completed.

Huibert Vos comments that there were “all kinds of reasons, internal and external” for the slow progress.

One issue was that Róisín Heneghan and Shi-Fu Peng had received their $250,000 winner’s fee but were not retained on the project. As a result, the project team had difficulty working out what some elements of the design were supposed to mean, and even opened a back channel to Dublin to find out.

In 2016 the government decided to get the project back on track.

It transferred responsibility from the antiquities ministry to the Egyptian Army’s engineering authority under Major General Atef Moftah, who became general director of the Grand Egyptian Museum project and surrounding area.

Over the next four years, until the advent of the pandemic, Gen Moftah succeeded in taking the project to 95% completion. He trained as an architect prior to his military career, and combined strong leadership with a hands-on attitude to architectural problems.

One thorny issue was the building’s façade. Heneghan Peng had envisaged a 46m wide, 12m high veil of translucent Macedonian alabaster, structured by fractal geometry and standing some 17m in front of the main building.

When it became apparent this would cost around $250m, Gen Moftah himself designed a façade from Sinai marble and Trieste limestone panels for less than a tenth of the cost. As a result, the project is expected to have a reasonable-in-the-circumstances cost of about $1bn.

The war of art

Gen Moftah is proud of the project team’s achievement in wrapping up almost four millennia in one building and presenting it as “a gift to humanity”, as he puts it. But the museum is designed to do more than just display and explain Egyptian history.

The success of the building and the sophistication of its conservation laboratories are intended to make a case for the return of countless Egyptian artefacts plundered over the years.

“We are seen as a place that is not able to preserve its own culture,” he says. “Whenever Egypt requests the return of stolen monuments, we meet with rejection and the world doesn’t really support us. The usual allegation is – why should we return it? It’s well preserved where it is, and you have the Tahrir Square museum as a storage area.”

“Every well-known museum in the world has an Egyptian section,” he says. “Some countries have several.” Top of a long list of items the Egyptians want repatriated is, of course, the British Museum’s Rosetta Stone and Nefertiti’s statue from Berlin’s Museum Island.

It may be a lengthy wait to achieve these goals.

The Greek government built the Acropolis Museum as a home for the Elgin Marbles 20 years ago, and yet they remain in Russell Square.

To underline the difficulty of persuading museums to release their plunder, Perihan Elwy comments that the Ministry of Antiquities had enough trouble persuading Egyptian museums to give up their treasured items, particularly those that relate to Tutankhamen.

The solar boats

Huibert Vos points out that the museum is just one element of a much bigger programme of work at the site and, after the museum opens its doors, much will remain to be done.

“We always call it a museum,” he says, “but really it’s more of a cultural complex. The museum is a corner of it. It takes up 90,000 sq m out of 430,000. There will also be a conference centre, an auditorium and teaching space, libraries, and storage areas functioning as archives, available for scholarly study. We have a big area for temporary exhibitions lasting two or three months, and then there’s the solar boat building, which isn’t there yet.”

This last reference is to two wooden boats that were discovered in 1954, disassembled into 1,224 small pieces and buried on the south side of the Great Pyramid. They are usually referred to as the Khufu ships, in reference to the Fourth Dynasty pharaoh who commissioned the pyramid, and they were intended to convey him on his onward voyage through the underworld to the afterlife.

The 43m-long boats are about 4,600 years old, making them the oldest wooden objects in the world. They are perfectly preserved – when found, they still smelled of cedar – but are very, very fragile. One was left as it was and the other was assembled and displayed intact in the former Giza Solar Boat Museum, built in situ between 1961 and 1982.

The plan is to display both boats together in a purpose-built annex – a high-risk strategy, given the extreme difficulty involved in disassembling the displayed boat and moving it to its new home.

To get an idea of how risk-averse the Ministry of Antiquities is, one has only to consider its caution in moving the Rameses statue in 2018.

That 400m journey required a specially surfaced road to be laid, and for the statue to be suspended from a steel beam to prevent any jolting from damaging its fabric – all this for an object made of limestone.

It was Gen Moftah who had the job of arranging things.

“The whole world warned Egypt not to move it,” he says, adding that it proved all but impossible to find a company willing to take the job on.

Finally, the general had the bold idea of moving the boat in one piece, after placing it in a sealed container inside a steel cage and demolishing the existing museum around it.

The technical side was planned over eight months by an international team of scientists, academics and engineers and carried out by Sarens, the Belgian heavy-lift specialist.

To accomplish the task, the Ghent-based company built a 52m-long, 5.6m-high steel bridge to allow a 12-axle self-propelled modular trailer (SPMT) to stop precisely underneath the 100 tonne cage containing the boat.

This then moved the weight as far as another 12-axle SPMT, fitted with specially designed shock-absorbers, which it parked on top of. The lower unit than began to move with agonising slowness to the site of the museum that would be built to contain it. The whole process took three days to complete.

At present, the annex is filled with temporary works, and it will be some time after the main museum opens before visitors can include Khufu’s barges in their trip.

Stage IV

The Grand Egyptian Museum is one of those projects that have significance beyond the purpose that it is being built to carry out.

Like Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam or China’s 2008 Olympic Games venues, it announces to the world that the country has entered a new stage in its development.

The museum is unusual in this respect because its focus is the past, but perhaps Egypt has to gain control of its extraordinary history before it can turn its attention fully to whatever comes next.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Wow