Authorities in Egypt have turned to a specialist engineer from Newport, Wales to stop one of the earliest pyramids from falling apart – but it took a long time for him to convince them that his diagnosis of the problem was correct.

Peter James FCIOB, 76, once deputy building superintendent for Cardiff city council, began restoring heritage stone buildings in Egypt after the devastating earthquake there in 1992.

Since then, his company Cintec has strengthened 22 mosques, the Temple Hibis, the Red Pyramid, and the burial chamber of Egypt’s oldest pyramid, known as the Step Pyramid.

But when he was invited to examine the thick, stone façade of the so-called Bent Pyramid at Dahshur (pictured above), which is slowly disintegrating, nobody believed his theory about what was causing the failure, which meant he could not get approval for his proposed remedy.

James himself perceived the cause when he first saw the structure up close in 2013. He put it down to thermal expansion, a basic natural phenomenon factored into building codes everywhere.

But archeologists, who hold sway at Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, were sticking to their favoured hypothesis, namely that it was a mix of foundation movement and robbers weakening the façade by stealing stones from it at some point in the past.

However, James persisted and now, thanks to a belated nudge from civil engineers at the University of Cairo, his theory has prevailed and the Cintec team is waiting for Covid travel restrictions to ease so they can go back and drill test holes to validate the solution.

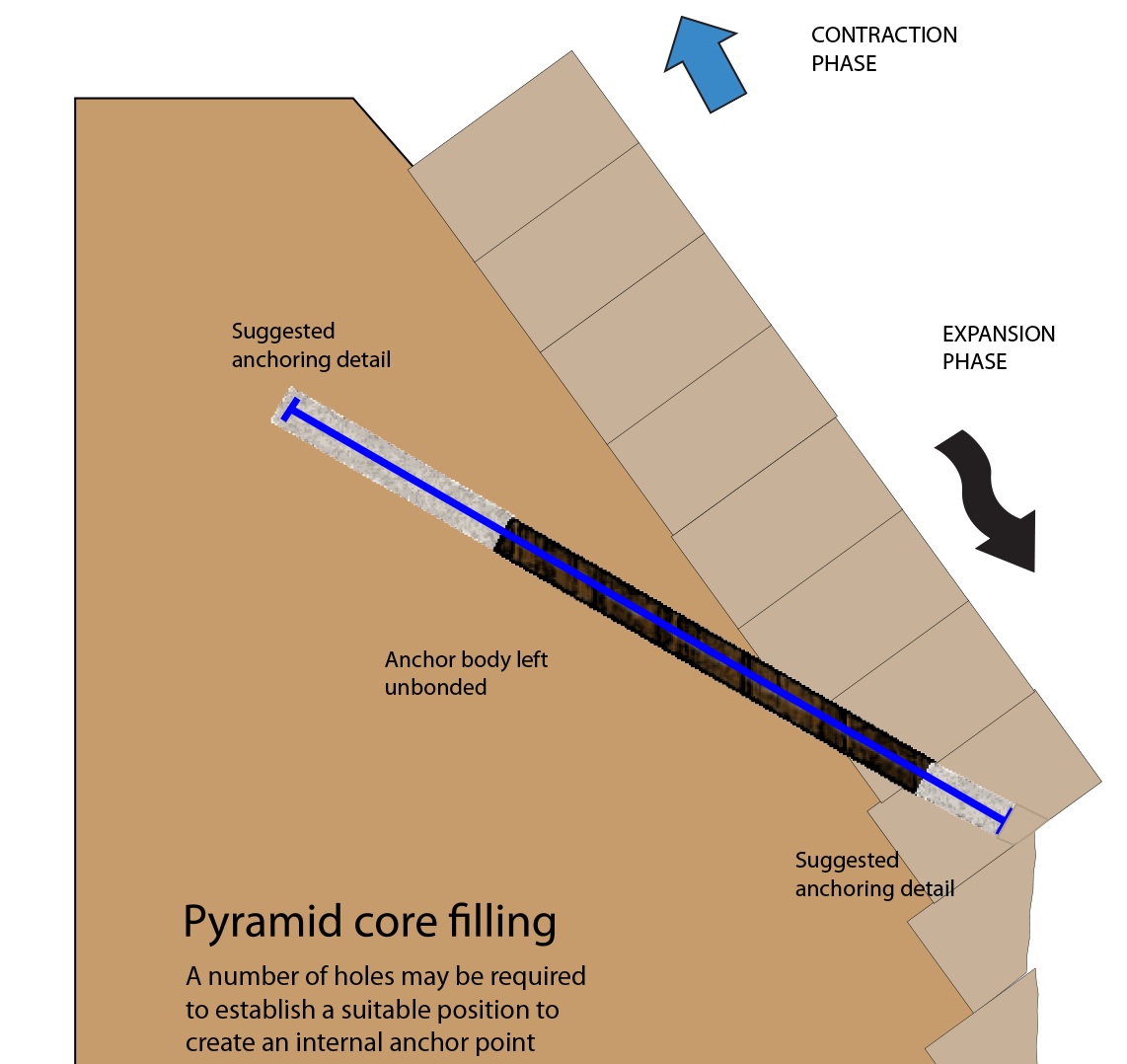

This would see Cintec’s proprietary anchoring system pinning the façade to the pyramid’s core in a bid to keep it intact for hundreds more years.

Cintec’s proprietary anchoring system will stitch the façade more securely to the structure while still allowing it to move (Cintec)

It matters because the Bent Pyramid, built some 4,600 years ago at a royal necropolis 40km south of Cairo, has retained much of its original façade, unlike all the newer ones, and the Egyptian government wants to stabilise the structure so it can be opened for tourism.

Eager to get started, James is celebrating the victory of physics over supposition.

“Archaeologists appear not to be trained in construction or natural science,” he told GCR. “They seem to think that because the blocks of stone are big, they don’t conform to natural laws dictating that when material is heated it expands.”

A gritty problem

James’s team submitted his assessment of the problem to the university in 2017, and it took two years for engineers there to weigh in behind it.

His assessment was that the façade, comprised of several layers of large, dressed stones with a total depth of between two and three metres, expands during the day as the temperature rises to an average of 40ºC, and contracts at night as the temperature plummets to an average of 3ºC. Taking into account seasonal fluctuations, that gives an average daily fluctuation of around 37ºC.

When the stones expand, dust and grit settle into the spaces, preventing them from returning to the exact position they had at the start of the daily cycle.

That means the fa̤ade faces have been spreading out Рexpanding their surface areas Рby minuscule amounts every day for 46 centuries. At the corners where opposing faces meet, stones buckle and snap off because they have nowhere else to go.

James calculates that in the seven years since he first saw the façade, the leading edges of its faces could have crept forward by as much as 50mm or more.

In 2014 Peter James received the Outstanding Achievement Award for innovation in heritage conservation from the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB)

“The archeologists’ theories didn’t make sense,” he said. “For one thing, there was no evidence of foundation movement. And for another, the pattern of collapse at the corners supports the theory of thermal expansion.

“The idea of mystery stone robbers doesn’t hold either. The stones coming loose are high up. You’d need elaborate scaffolding to get at them, and it would be a very dangerous business. Then you’d need to lug them 40km back to Cairo, when there are stones just as good in the hills around the city. I just can’t see anyone doing that.”

Saved by its eccentricity?

The third oldest pyramid still standing, and the second to be commissioned by the Pharoah Sneferu, the Bent Pyramid marks the last stage in the evolution of pyramid design from the terraced, wedding-cake look of the Step Pyramid to the “true” shape first seen in the next one to be built, the Red Pyramid, Sneferu’s fourth, also at the Dahshur necropolis.

The Bent Pyramid’s builders began ambitiously, setting a course for the sides to rise up from the ground at a skyscraping incline of 54º, which meant it would have eclipsed its predecessors in size while achieving the startling, otherworldly symmetry the later pyramids have.

But it seems they bit off more than they could chew because a little over halfway up they suddenly changed the angle of incline to a much shallower 43º, which turned it sharply inwards, giving the pyramid its eccentric “bent” look. James agrees with the theory that they did this because the load bearing down on the burial chamber inside was growing enormous and was threatening to crush it, so they nipped the pinnacle off early to lessen the load.

In James’s view, this eccentricity helped to preserve the façade because the space between each face’s two planes acted as an expansion joint, giving them some room to move.

James also believes that the standard of masonry is rougher in the Bent Pyramid, with more gaps between the stones (leaving extra room for thermal expansion) than in the precision stonework of the newer, “true” pyramids, which lost their façades long ago.

The façade faces have been expanding their surface areas by minuscule amounts every day for 46 centuries (Supplied by Peter James)

“I expect the builders of the newer pyramids would have seen their façades coming apart at the corners within 20 or 30 years after they’d been built,” he said. “They knew an impressive amount about engineering, but they never learned about thermal expansion.”

Proceed with extreme caution

Buoyed by the university’s support, James finally got a meeting with the Supreme Council’s deputy head in July last year, at which he received approval to use diamond drilling to bore 10 holes to insert test rods, some 5m in length, that will anchor the façade to the pyramid’s core.

The stainless steel anchors will expand and contract with the stones, and will be fitted with a device that measures the exact amount of daily movement occurring over a period of about two months. The movement logged should put his theory beyond doubt. It will also give Cintec the data it needs to design a bigger batch of anchor rods that will stitch the façade more securely to the structure.

It won’t stop the thermal expansion altogether – the kilonewtons of force required for that would entail drastic alteration of the pyramid’s entire structure – but it should slow the expansion down significantly.

At the meeting the Council gave the go ahead, but on one condition. Nobody has drilled into pyramids before, so Cintec would have to do ground-penetrating radar scans of the areas behind the façade to ensure they were not disturbing any undiscovered voids. “They worried we might drill into a chamber and knock over a vase,” James said. Fortunately, the scans performed at the end of 2019 revealed only more rock.

In early 2020, Cintec was assembling equipment for the test drills, which it is carrying out free of charge, when the pandemic struck, postponing this unprecedented operation. Understandably, James is impatient to start.

A very active brain

It has been quite a journey from overseeing a large force of tradesmen at work maintaining Cardiff council’s building stock to being the go-to guy for fixing Egypt’s pyramids.

In late 2019, Cintec conducted ground-penetrating radar scans of the areas behind the façade to ensure they would not disturb any undiscovered voids (Cintec)

He began learning on the job in 1960 with WS Atkins but found civil engineering construction, with all its acres of concrete, “too coarse”.

At Cardiff council he grew to respect the trades at a time when the quality of craftsmanship was valued over the quantity of it, a sensibility that drew him to subtle approaches to heritage repairs.

In 1985 he founded Cintec, a niche firm specialising in patented reinforcement systems, which led to high-profile work on, among numerous places, Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey and the White House.

He was recommended to Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities by a UNESCO engineer who saw his work in the restoration of Windsor Castle after the devastating fire there in 1992, the same year as the fateful earthquake in Egypt.

Cintec restores heritage structures all over the world; at time of writing, the company had just finished using its anchoring system to pin back together a delicate, 500-year-old stone bridge that had lain broken in pieces in the river it spanned since an earthquake in 2009.

In 2014 James received the Outstanding Achievement Award for innovation in heritage conservation from the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB).

He attributes his technical confidence to years of self-directed learning. As was common in the 1960s, he didn’t go to university but qualified with a Higher National Certificate in construction. Any gaps in his knowledge he filled with voracious reading.

“I have a very active brain and I read millions of books on structures, and natural sciences as well,” he said.

- Peter James’s book, Saving the Pyramids (2018) is published by University of Wales Press.

Top image: The Bent Pyramid is the third oldest pyramid still standing, and marks the last stage in the evolution of pyramid design (Supplied by Peter James)