Nuclear reactors come in three forms. The largest are the 700MW-plus units that power entire countries and are produced by a handful of national champions, the largest three being Areva, Rosatom, and GE-Hitachi.

Then there is a field of more than 50 companies racing to develop small modular reactors, or SMRs. These come in many shapes, with a range of fuel types and coolant systems, but they typically have an output of between 100 and 300MW.

Finally, there are the microreactors, or μSMRs, which are found in university physics departments and the engine rooms of aircraft carriers, icebreakers, and submarines. These generally have an output of 50MW or below.

At first glance, it might seem that microreactors would have many commercial uses, since the world is filled with mines, military bases, and isolated communities who need electricity but don’t have access to a grid.

Then there are the data centres and cryptomines that could be attached to a grid, but would rather have their own supplies for reasons of expense and security of supply.

Very few microreactors are used commercially. The most notable example in recent years is the Akademik Lomonosov, a Russian nuclear barge that was developed over 14 years and is now moored off the port of Pevek in Russia’s Far East.

Two years ago, however, US start-up Nano Nuclear Energy began trying to bring a commercial microreactor to market.

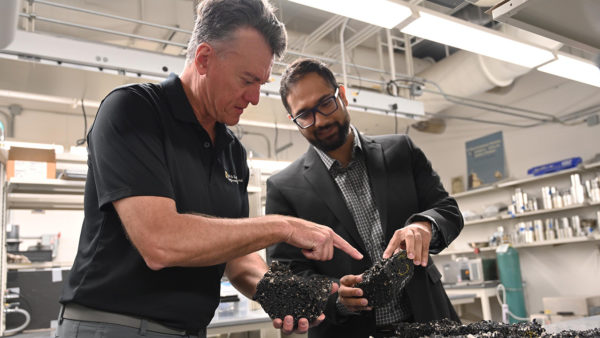

To find out what this involves, GCR talked to Jay Jiang Yu, the company’s New York-based founder and president, and chief executive James Walker, a nuclear physicist who has worked for the UK Ministry of Defence.

Why micro?

It was precisely the undeveloped nature of the market that attracted them, Walker said.

Back in 2021, the pair considered all forms of renewable energy before opting for micro nuclear as the sector with the fewest external constraints and the greatest untapped potential.

What’s more, military microreactors use highly enriched uranium, whereas the fuel used in civil applications must remain under 20%.

“There are no microreactor prototypes and no licensed microreactors,” Walker said. “In fact, I don’t think there’s a public microreactor company. So the race is very much on. We thought, if you started with good science and engineering you could easily pull into the lead.”

So, in 2021 the company began hiring scientists and engineers, mainly post-docs and professors from Berkeley and Cambridge. The brief was to design a reactor with almost no moving parts that could be put into a shipping container and moved anywhere in the world. The concept was to develop a unit with the portability and convenience of a battery, and the initial aim was to replace expensive, noisy, polluting diesel generators.

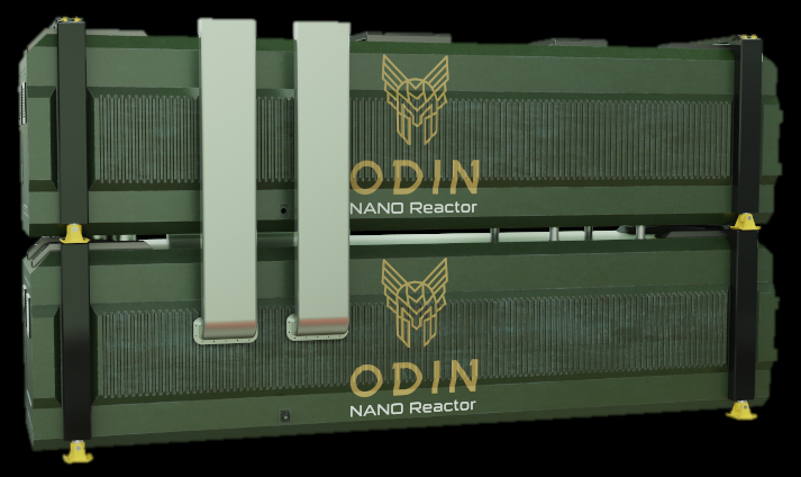

In the event, the company developed two reactors: Zeus and Odin, both with an output of 4MW thermal and 1.5MW electrical.

The former has two solid core reactors that operate without coolant. This, says Walker, is about as simple as a design can be.

The latter is even smaller, about a cubic metre.

They developed two models to give investors options, and to create a complementary development process.

“We can turn the Zeus designs over to the Odin team so they can run the models and look for anything that might have been missed,” Walker said.

Timelines

Nano Nuclear has completed two funding rounds. The first saw enthusiastic buy-in from former executives at the world’s biggest shipping company, who liked the idea of reactors that could be shipped around the globe. The second round was monopolised by an unnamed billionaire. That was enough to grow the business to a headcount of 30.

Next year there will be another round, and possibly an acquisition that would increase staff numbers to several hundred. Jay Jiang Yu, who has worked on Wall Street, says the aim is to “grow the business tremendously”.

Finding money isn’t difficult, he said: the tricky part is maintaining control.

“We have a lot of financing opportunities. Even banks have told us they’ll fund us, but they want to have a lot of control of the company and we’re not willing to do that. We want to stay in control. A lot of VC and private equity funds will give you all the money you want, but they want control of your board. We think we have something special and we have ultra-high-net-worth people willing to back us.”

The next step is to build prototypes and test them. This will take the company up to 2026, when enough will be known about the design to begin the licence application process. The firm expects this to be complete in 2030, whereupon the product will be ready for rapid dissemination to buyers.

Obviously, this process will have costs, and no revenue from reactor-buyers for around seven years. How will the business stay in business for that long?

The aim here is to develop auxiliary services in the nuclear realm, hence that acquisition pencilled in for 2024. Walker lists consultancy services such as nuclear security and safety. There is also a plan to build the US first commercial “category II” fuel fabrication facility in the US. This could produce TRISO fuel, made up of tiny kernels of uranium, carbon and oxygen.

Licensing

Getting approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) will be a major hurdle.

The first US company to do this for small, manufactured reactors was NuScale, and it cost the company some $500m.

Happily for that business, it received its approval and went on to become a listed company with an enterprise value of about $1.9bn, although it did have to sell 60% of its equity to Texas engineer Fluor along the way.

Nano Nuclear can follow NuScale’s slipstream to get through the process with less effort and expense.

Says Walker: “They were presenting the NRC with a lot of things they hadn’t seen before, and the benefit for the nuclear industry in general is that anyone who follows them has a much easier time of it.

“And because a lot of that information is public, other companies have an insight into what they have to do to get licensed. We know what questions will be asked and what regulations and standards we have to meet. We’ve engaged with the NRC and we’ve said these are our timelines and can you book people for when we will need them in 2026 and 2027?”

That said, licensing is still the longest lead item, longer than design and prototype-testing combined. The aim is to get approval in 2030 and to begin shipping units the next day.

“We’ve already started talking to some major mining firms that are interested in decarbonising and we’re co-funding feasibility and scoping studies, including for individual sites,” Walker said.

“Say there’s a big iron ore operation: We’d look at what can be electrified at their site – EVs, electric trucks, accommodation and so on.”

The future

Nano Nuclear is hoping to begin selling electricity to the grid while it is still in the research and development phase, and it is presently in talks with a utility in the western US about setting up a generating site – hopefully with more success than NuScale had in Idaho.

The company is hoping to tap into markets around the world by simultaneously licensing its reactors in the US, UK, Europe, and Japan.

Of course, the future of any generating technology depends on a great many imponderables, including the mood among governments and publics, and the changing cost calculations of nuclear in relation to other ways of producing electricity. A historical survey of big nuclear, for example, shows just how much the fortunes of an industry can change from one decade to the next.

Nevertheless, the marriage of cost and convenience that microreactors can conceivably deliver may make this particular branch of the growing nuclear family a reasonable bet for the future. We do have a bit of a wait to find out, though.

Further reading: