Catastrophic flooding in Libya this week highlights the worldwide risk posed when record-breaking rainfall meets inadequate water infrastructure, experts warn.

The death toll in the Libyan city of Derna reached 11,000 yesterday, with 20,000 people still missing, the Red Crescent said.

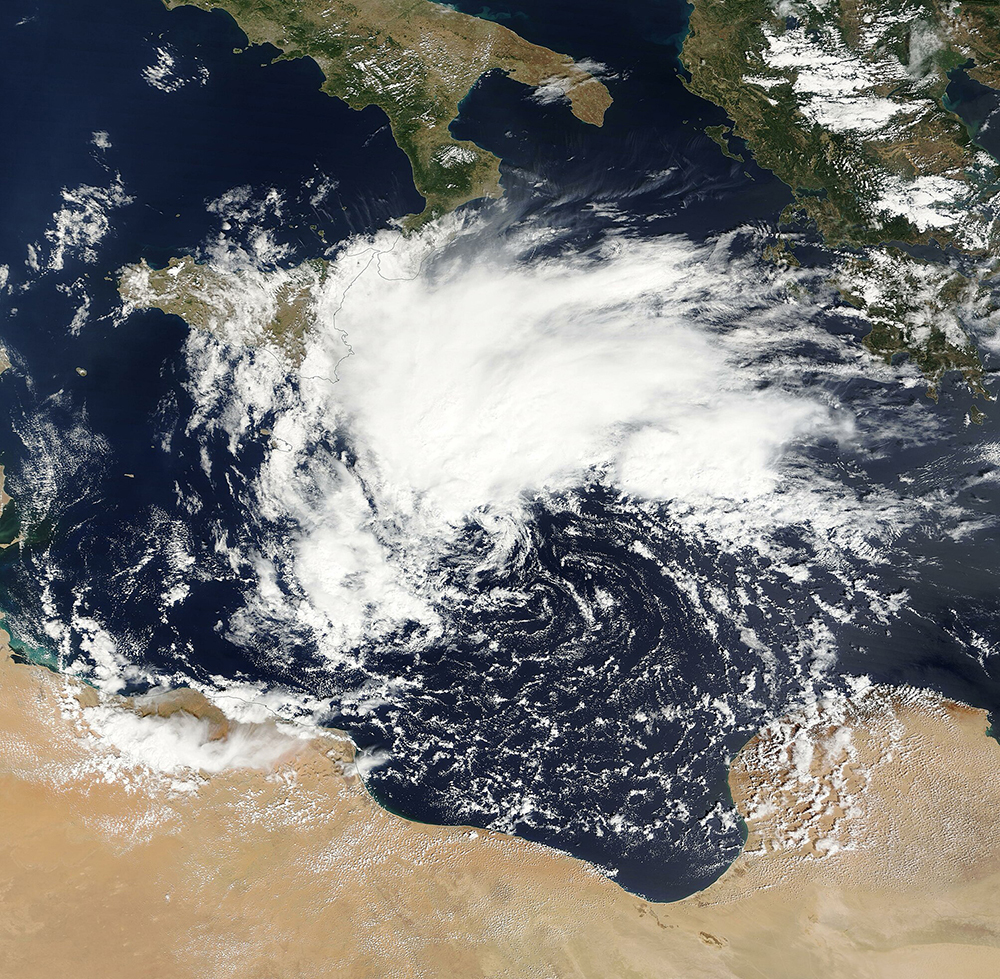

The city of 100,000 was decimated when Storm Daniel struck Libya’s northeast coast after causing havoc in Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria.

Experts say such events will become more common as the earth warms, and coined the phrase “gray swans” to describe them, meaning events that are rare and catastrophic, but increasingly predictable.

The warning comes as tens of thousands of large dams around the world protecting billions of people approach the end of their design life.

What happened at Derna

Storm Daniel dumped unprecedented volumes of water in a short time onto the arid northeastern coast of Libya.

The city of Al-Bayda, some 100km to the west of Derna, recorded 414mm of rain in 24 hours between Monday and Tuesday mornings. That’s 16 times the average annual rainfall in the whole country. Libya’s National Meteorological Centre deemed it a record.

In Derna, the water coursed down the Wadi Derna River that runs through the city to empty into the Mediterranean. Its bed is often dry, but on Monday a wall of water seems to have broken through two dams built in the 1970s at different locations upstream, leaving Derna residents little chance to escape.

A deputy mayor of the city told Al Jazeera the dams hadn’t been maintained for 20 years. As recently as November 2022, a Libyan civil engineering academic published a paper warning of flood risks on the river and calling for regular dam maintenance and the planting of vegetation to halt desertification and erosion.

Such maintenance is difficult in a country riven recently by civil war and ruled by two rival governments. Nor is it clear whether the dams would have prevented the flood had they been maintained.

Meteorologists call Storm Daniel a “medicane” because it is a hurricane-like storm occurring in the Mediterranean.

Scientists say evidence suggests global warming decreases the frequency of medicanes but increases the strength of the strongest ones, as well as the volume of water they carry.

‘Gray swans’

This week, two academics from Boston’s Northeastern University coined the term “gray swans” to describe events like the Derna catastrophe.

Where “black swan” events are catastrophes that could not reasonably have been predicted, like the 9/11 terror attacks, gray swans are catastrophes that become more predictable as the earth’s surface warms.

This shines a glaring spotlight on water infrastructure such as reservoirs, dams and levees.

Auroop Ganguly, Northeastern’s distinguished professor of civil and environmental engineering, cited the failure of levees during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005 and this year’s and last year’s devastating floods in Pakistan as examples.

“The infrastructure has to be ready for these sorts of events,” he said. “If you’re thinking about, for example, long-term climate variability and change – that should impact the design of hydraulic infrastructure, and the design of dams and reservoirs.”

Other examples may be the Oroville Dam in California, where 188,000 people were evacuated in 2017 when it seemed rising water levels might threaten the dam’s spillways; or two years ago in Vancouver when heavy rain swelled the Fraser River and cut the city off from rail and shipping.

His colleague Prof Daniel Aldrich, director of the university’s Security and Resilience Program, said infrastructure investment needs to account for gray swans.

“What we’re seeing is absolutely a consequence of the way we prioritise investments in different types of systems,” he said. “When we built these dams, we certainly didn’t have in mind the irregularities we’re seeing more often.”

Elderly dams around the world

By 2050, most people on Earth will live downstream of tens of thousands of large dams built in the 20th century, many already operating at or beyond their design life, according to a 2021 report by the United Nations’ Institute for Water, Environment and Health.

It said that at 50 years, a large concrete dam “would most probably begin to express signs of ageing”.

More than 85% of dams in the US were operating at or beyond their life expectancy, it found.

It said that in India, more than a thousand large dams will be 50 years old in 2025. One of these, the 100-plus-year-old Mullaperiyar dam built in a seismically active area would endanger some 3.5 million people if it failed. The report says its management is a contentious issue between the states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

55% of the world’s large dams are found in China, India, Japan, and South Korea, with a majority of them turning 50 relatively soon.

The same is true of many large dams in Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe, the report said.