A digital revolution has swept through global industries. Telecoms, media, retailing, hospitality, manufacturing, transport, financial and business services have all been transformed as technology creates new ways to produce, distribute and consume their products.

Even construction, that most Biblical of trades, is facing the prospect of disruption as advances in robotics, autonomous vehicles, drones, laser scanning, telematics, augmented reality, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning begin to influence how work is carried out on site.

However, anybody who has witnessed the painfully slow diffusion of building information modelling (BIM) throughout the industry will know that construction is struggling to go digital, no matter what productivity gains may be on offer.

A possible main reason for this is the industry’s extreme fragmentation. But it may also be the difficulty of imagining what role digital technology might play in the stubbornly physical world of the construction site.

So, how about creating a real building site and using it to demonstrate as many emerging technologies as possible? That was an idea that occurred about a year ago to Mike Sicilia, general manager of the construction and engineering division of tech giant, Oracle.

The Deerfield experience

“We spent a lot of time with customers talking about solutions in conference rooms, but that’s not where they work,” he told GCR. “They work on job sites in harsh conditions. I think there’s something that comes with using the technology on a real site that you just don’t get when you’re sitting around a table.”

This led to the Construction and Engineering Innovation Lab, which opened in the north Chicago suburb of Deerfield on 23 August this year. The site brings together construction practitioners and academics to examine how digital technologies interface with a site’s analogue systems, including human workers.

Confirming his hunch that the industry was keen to see tech at work in the real world, the lab has attracted lots of attention from industry and academia. Sicilia said people turned up two hours early on opening day.

The trick is to connect digital and analogue elements of the site (Oracle)

Much of what can be seen at Deerfield is not produced by Oracle, but rather by its partners. For example, it showcases extended BIM software from Autodesk’s Assemble Systems, augmented reality headsets from DAQRI, connected tools from Bosch and labour productivity systems from Reconstruct as well as Oracle’s “Live Experience Cloud”.

Oracle is in the process of building a second site that will be inside a permanent structure similar to an aircraft hangar, to simulate a site after it is structurally complete. This will open next year.

This approach is in line with the development of a “digital ecosystem”, in which companies offering complementary products and services link up to offer customers a seamless experience. As Sicilia says, the separate systems are bolt-on and modular, so customers don’t have to “stitch together” systems on their own.

The rush to invest

It is also a sign of how of how many companies are developing digital products, and how much investment is flowing in to this space. According to Sicilia, there is more venture capital finance available now than he’s seen in his 25 years in the business, which he says is a recognition of how ripe construction is for upgrading.

Oracle itself is a leading investor. It entered the construction space in 2008 when it bought Primavera Systems, a project management software specialist. Sicilia, Primavera’s general manager, joined Oracle as part of the deal.

Oracle then spent $663m on the Textura cloud-based payment management system in April 2016, and this has since handled more than $500bn in disbursements to subcontractors.

Then in 2017 it acquired Melbourne-based Aconex for $1.2bn, which was 46% above its market value. Aconex writes software, also cloud-based, that allow teams working on building projects to collaborate and share documents.

These moves no doubt reflect Oracle’s desire to increase its revenue, which rose from $11.8bn in 2005 to $37.1bn in 2012, but has stayed more or less constant ever since.

Company founder Larry Ellison wants Oracle to grow by providing the best cloud computing services, and construction would be a huge market.

The lake in the clouds

It is possible that tech giants like Oracle will be able to use the cloud to modernise construction in a way construction cannot manage by itself.

All now-digitalised industries find the way they collect, filter, analyse and discard data assumes a new importance, which is where Oracle comes in. The cloud has the effect of bringing data together regardless of format, thereby overcoming the interoperability problems that have dogged construction IT since the invention of CAD.

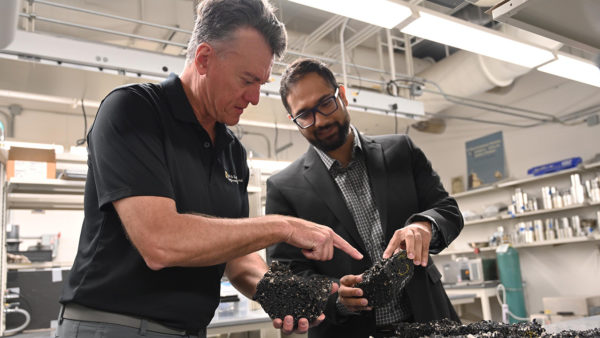

Oracle’s construction leader, Mike Sicilia (Oracle)

The availability of these cloud-based data “lakes” is an essential precondition for the site of the future, in which planning, design, procurement, payment, scheduling, surveying, construction and management are part of a single, digitally integrated process.

“Aconex and our other modules generate a tremendous amount of data, and customers sometimes have a difficult time understanding their own data, because it’s not a trivial thing,” Sicilia says.

“By embracing the Oracle technologies around big data and analytics, which we’re doing right now, we plan in the next calendar year to offer what we think are some pretty compelling analytics that will span all of our modules and also allow customers to plug into third-party modules as well.”

As an example of what will be possible with cloud-based analytics, Sicilia mentions a large infrastructure project in which about three-quarters of the workforce are subcontractors or suppliers. The success of the project depends on the competence and collaborative skills of these firms, and how well they are managed by whoever’s in charge of the work.

Clearly, to control the site, it is necessary to collect a huge amount of information about who these subcontractors are and how well they are performing. So, Oracle will aim to create analytics dashboards that give site and project managers a 360° view of each company working on the job, everything from its financial soundness to the jobs it is pre-approved to do, and combines them with detailed records of its past performance.

In the future, Sicilia adds, machine learning and AI may be able to sift through huge amounts of past data and use it to prevent mistakes.

How far in the future?

“This is the right time to be investing in augmented reality and machine learning,” he says, “but I think these things usually take a period of three to five years to become normalised within an organisation.

“We are on year one of a five-year horizon, and this is exactly why we built the innovation lab. We need many customers to come in so that we can have these discussions and get real-time feedback.”

Top image: Jovix’s drone-mounted RFID reader in action (Atlas RFID)

Further reading: