Technical breakthroughs are bringing back the airship, and remote construction projects could benefit.

In a revival of a technology that fell spectacularly from grace after the explosion of the Hindenburg in 1937, US aerospace firm Lockheed Martin is now taking orders for a giant airship that can carry heavy loads to remote areas.

Major building projects in places lacking road or rail could benefit from the modern-day Zeppelin, which the company says offers a cleaner, quieter and cheaper way of transporting large payloads.

Lockheed Martin has spent the past 20 years developing a “hybrid” vehicle, so called because it derives 80% of its lift from its helium envelope and 20% from either aerodynamic lift (as provided by an aircraft wing) or from direct lift (as provided by a helicopter’s rotor).

We’ve invested more than 20 years to develop the technology, prove the performance and ensure there are compelling economics for the hybrid airship– Orlando Carvalho, Lockheed Martin Aeronautics

Four propellers move it or hold it in position, and it has a suite of modern avionics and computer controls.Â

Lockheed believes there is a market for the hybrid in moving loads over the two-thirds of the world’s land area that has no access to paved roads. The company claims that it is just as manoeuvrable as an aeroplane.Â

Last month, the company used the Paris air show to announce that it is now taking orders for hybrids, with delivery possible in early 2018.Â

The first model has a lifting capacity of 20 tonnes and will be assembled at Lockheed’s facility in Palmdale, Los Angeles.

Orlando Carvalho, executive vice president of Lockheed Martin Aeronautics, said: “We’ve invested more than 20 years to develop the technology, prove the performance and ensure there are compelling economics for the hybrid airship. We’ve completed all required FAA certification planning steps for a new class of aircraft and are ready to begin construction of the first commercial model.”Â

Troubled history

Back in the 1930s it wasn’t completely clear how aeroplanes and airships were going to share the air-freight and passenger market.

Planes were faster, but the airship was a technology with a century of development behind it and, by 1931, there was still sufficient confidence in its future to fit an airship mooring mast to the top of the Empire State Building.Â

The question was decided by a number of disasters, however, the best known being the destruction of the Hindenburg in 1937, before a large crowd in New Jersey.

After that, the dirigible airship and its non-rigid cousin, the blimp, were reduced to menial work in the advertising and tourism industries.

But the golden years were never forgotten, and there have been a number of attempts to bring it back to commercial operation, based partly on its inherent advantages and partly on new technological solutions to problems that were insoluble in the 1930s.Â

Arriving safe and soundÂ

Despite the theoretical safety advantages of flying in a vehicle that’s lighter than air (and will therefore float rather than fall if something happens to the engine), large airships turned out to be very dangerous indeed.

Airships could move wind components across the vast landscapes and over borders of southern Africa, and bringing renewable energy power sources and equipment to rural villages in India– Igor Pasternak, Aeros

The main problem was that, when landing, the airship could not dispense with its lifting gas, and so was a highly unstable load to wrangle into position.Â

One firm challenging Lockheed for the future dirigible market is Aeros, a firm founded in California by a 51-year-old Ukrainian émigré called Igor Pasternak. Fascinated by airships since boyhood, Pasternak made a breakthrough in the way they can be landed.

He developed a way rapidly to compress the helium in the airship’s envelope, replacing it with air.Â

This was then married to his design for the Aeroscraft: a beast that was quarter of a kilometre long, could travel at 220kmh and carry 250 tonnes over 10,000km. These performance specifications were enough to get Pasternak a $60m development grant from the US military, and the first model is due to be in the air by 2019.

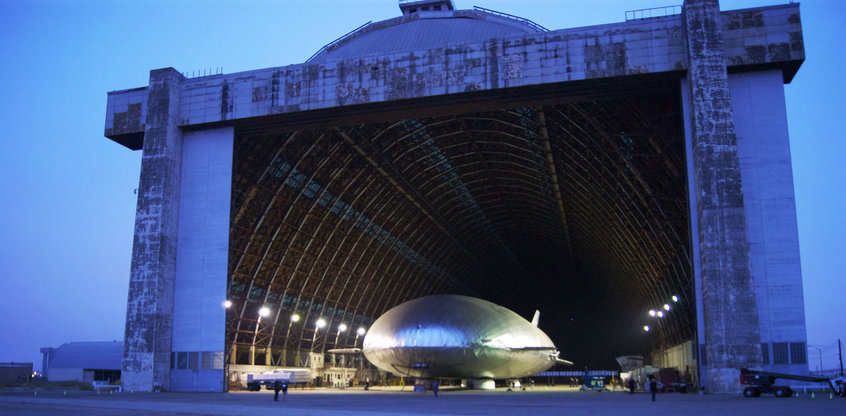

Pasternak’s first prototype airship, built in 2012 (Source: Aeros)

The company is also working on smaller versions: its 40D Skydragon has been certified by America’s and Mexico’s aviation regulators and sold to a Mexican operator. Production has begun on the 40E version, and although its performance statistics are modest compared with the Aeroscraft (2 tonnes carried at 100kmh), it is at least in the game with a chance of reaching Pasternak’s goal of building a 24-vehicle fleet, half of which will be in operation in the Arctic, South America, Africa and India.Â

Colonel Blimp

Ever in need of innovative logistical solutions, the US military has been as fascinated by airships as Pasternak.Â

The high point of military interest came in the 2000s, when the Walrus HULA (Hybrid Ultra Large Aircraft) was launched by the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the part of the US Department of Defence that has the job of “expanding the frontiers of technology”.Â

It wanted an airship capable of traveling 22,000km while carrying 1,000 tons of cargo, and the programme looked at radically new propulsion methods, such as electrostatic atmospheric ion propulsion.

Operation Walrus was killed off by the US Congress in 2010, but the US military has not forgotten airships, as its funding of Aeros demonstrates.Â

How the Defence Department envisaged the Walrus: notice the stubby “Thunderbird 2” wings (Source: YouTube)

The US may also be spurred on by the fact that the Russians are getting one.Â

Just last week that the Russian military announced that it would have its 130-m-long, $15m “Atlant” hybrid operational by 2018.Â

This is modest by DARPA standards, having a payload of 60 tonnes and a speed of 140km/h, but it does show that more than one military sees the potential of the hybrid.

Russian’s Atlant military hybrid (source: RosAeroSystems)

The fallen

So it seems that the airship is staging a comeback, but a word of caution: many airship companies, most of them founded by undercapitalised enthusiasts, have crashed and burned like the Hindenburg.

For example, visitors to Berlin can make a daytrip to the “tropical resort” in the former hangar of the Cargolifter company, which was set up in 1996 to provide a similar service to Lockheed’s Hybrid: a ship that could carry up to 160 tonnes wherever it was required. It declared insolvency in 2002, leaving some 70,000 investors $330m out of pocket.Â

And even giant companies have not succeeded: back in 2008 Boeing announced that it was teaming up with Canadian operator Skyhook International to produce a heavy lift “buoyancy neutral” helicopter, but the scheme was quietly dropped a couple of years later.

But if the airship concept is proved, and if commercial investors decide that there is enough of a market, the construction industry may be a prime beneficiary.

Aeros’ Pasternak sees one important task as transporting infrastructure for wind and solar farms. He has stated that airships could move “wind components across the vast landscapes and over borders of southern Africa, and bringing renewable energy power sources and equipment to rural villages in India”.Â

Certainly, for large projects in remote areas, such as Lake Turkana in Kenya, the capacity to move 365 delicate turbines to site without first building transport infrastructure would be a significant advantage, and in many cases may mean the difference between going ahead or not.

Other specialist construction, such as military bases in geographically sensitive areas such as the Arctic Circle may be able to get their building materials by airship, a process known as “roadless trucking”.Â

And industrial projects that need very large, heavy machines to be transported in one piece from a fabrication plant to the site, then lowered into the exact location, would have obvious appeal for anyone project managing, say, a chemical plant or a steelworks.

Then there is the intriguing idea of using an airship in areas where trucks cause congestion or cranes cannot be fitted. This method, known to the airship fraternity as ‘short haul, heavy lift’, would offer a whole extra dimension to site logistics.

Aeros’ new generation airship with enhanced landing ability (Source: Aeros)

Comments

Comments are closed.

A monolithic sheath, combining Graphene technology and woven substrates, supported by an integrated superstructure, which would allow the hull to respond uniformly to external stress, such as micro-bursts and other atmospheric anomalies. This would enable the conjoining of modular multiple hulls, that separate and land at specified locations. Ideal for shipping centers and high volume merchandisers like Amazon.

Any likelihood of eventual affordable dirigibles as homes–as some do with a sailboat?

Well I’ve been thinking about this idea for a couple of decades now. Given all the forest fires as of late, I think it’s time to share this with a group that has the resources to move this thought to potential fruition. My idea is this, A heavy lifting airship designed in such a way, that it could land atop a body of water and fill several onboard tanks with water. Once ship is full of water, it would than lift off and proceed to a large fire, seemingly out of control. Once on station, water would be shot from a series of water cannons located about the perimeter of the ship. The bottom and sides of the ship would be fire protected by tiles similar to the ones used on the space shuttles during reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere. If the ship was designed to carry say, 1,000 tons. That would equate to 269,000 gallons of water or fire retardant of some kind. Some of this capacity would be lost due to the fire fighting equipment needed aboard ship to expel water or retardant. The ship would of course try to avoid stationing itself over the fire but would stay just outside the periphery of the main blaze. This ship in conjunction with ground support would extinguish the fire much faster and avoid billions of dollars and life that would be otherwise lost in the ensuing fire. Some cases, may require two or more of theses type ships rotating back and forth from the site of the fire, depending on its location and intensity. When not in use at fire locations, the ships could be used to clear congested remote areas of dead trees etc. with help of ground forces in the same location. Larger equipment could be lowered from the ship into the forest fully fueled as needed. Smaller dozers and the like. If developed and used as I’ve described, I would like to be acknowledged in some sort of way. Seems befitting.

In response to Chris Webster, your idea to use airships to carry 1000 tons of water to fight fire (and for forest management) has been discussed before. This does not detract from the fact that you were creative enough to come up with the idea, but since it was discussed before, yet has not been done yet, this shows that it is very challenging to accomplish. The main challenge is to build an airship that will lift 1000 tons. There are two parts to this challenge. The first is to keep the structural weight from using up all of the buoyant lift. This challenge gets harder, not easier, as the size gets bigger. The second is how to handle the difference in load as the water is picked up and then dropped. The two main ways of doing that, changing the buoyant lift, and using aerodynamic force, are being applied. So far, no one has been able to get close to 1000 tons. I am a mechanical engineer, and I have been cogitating about this challenge since I first became aware of it in 1987. I now think I know the correct approach to get the maximum lift, although no one will know how much that is until the last bolt and cable are accounted for.