Robotic suits of one kind or another have long been a staple of comic books and science fiction, but here in the real world industries are now looking seriously into fitting workers with external skeletons able to boost strength without reducing physical co-ordination. Â

It has been suggested that surgeons could use exoskeletons to improve hand control during operations, and their patients could wear them to overcome disabilities.

The military has also shown an interest, more for the potential of increasing a soldier’s carrying capacity than to allow them to wield improbably large guns.

But these are somewhat niche functions. Where these suits would really find a mass market is in industries that require physical strength, and where the performance of ordinary tasks is known to damage workers’ bodies.

Before now, nobody has managed to calculate the person and the surrounding exoskeleton as a single unit– Carmen Constantinescu, Fraunhofer

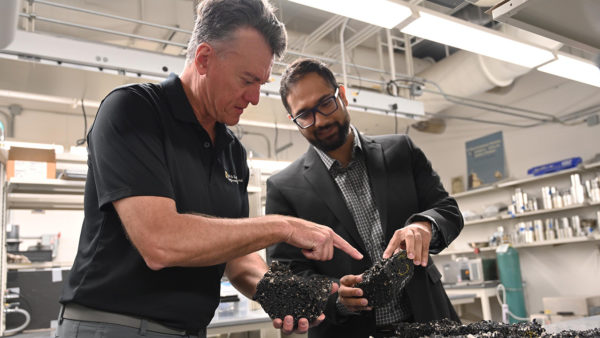

The construction industry is a prime candidate. Quite apart from the potential boost to a worker’s productivity, the suits may be able to preserve their wellbeing. Â

On UK sites, musculoskeletal injuries have a total healthcare cost of about $1.6bn, and more than a third of workers over 50 suffer chronic back pain. Â

In construction as well as manufacturing, the principal cause of injury is overexertion, rather than the performance of repetitive tasks.Â

A number of projects are developing commercial exoskeletons around the world. The one currently in the headlines is Robo-Mate, a project funded by the EU with the aim of keeping manufacturing jobs in Europe.Â

A prototype was on display at the Stuttgart headquarters of the Fraunhofer Institute, a technology research organisation. Â

Euroman?Â

Wernher van de Venn, the co-ordinator of the project and head of the Institute of Mechatronic Systems at Zurich University, explained to Phys.org: “Our prototype consists of modules for the arms, the trunk of the body and the legs.” Â

The arm modules use motors to reduce the force needed to move an object by a factor of 10 – which means a worker on site would be able to lift 200kg as though it were 20kg. Â

As the momentum of the mass would not be reduced, the trunk section has to stabilise and protect the back and spinal column. Meanwhile, the leg modules stiffen and form a kind of seat when the person in the suit squats to pick up a heavy weight, so that the knee – the most vulnerable spot on the human body – is protected.Â

The scientists at Fraunhofer developed the suit using software that simulates the sequence of movements a body adopts when it manipulates object in its environment. This identified the strain points that the exoskeleton would need to alleviate. Â

“Before now, nobody has managed to calculate the person and the surrounding exoskeleton as a single unit,” said Carmen Constantinescu, who is running the project for Fraunhofer.

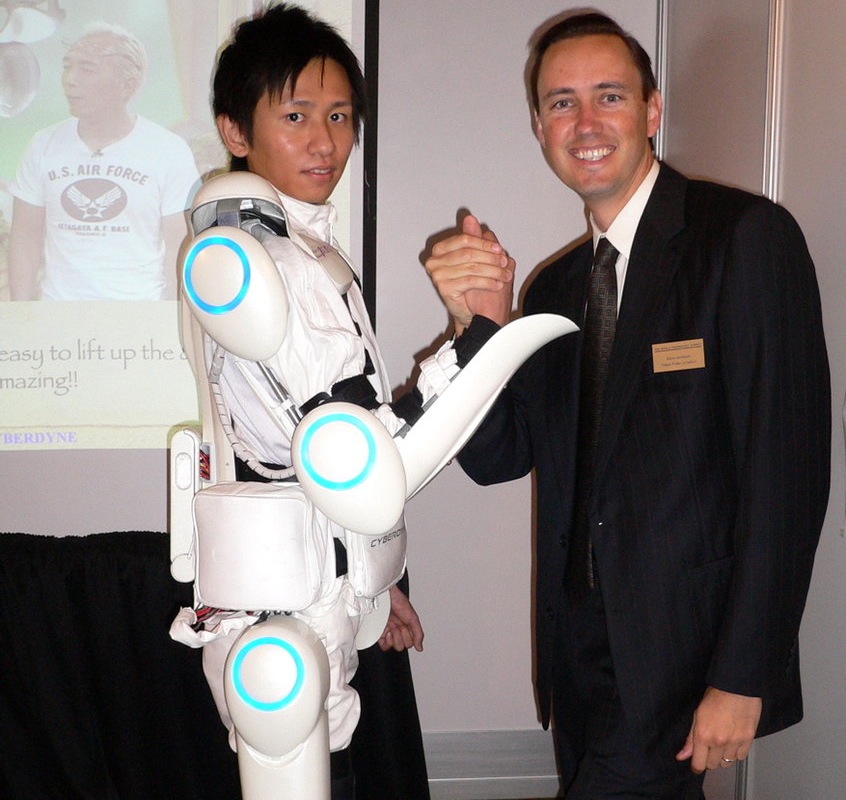

The “robot suit” produced by Japan’s Cyberdyne assists people with impaired mobility (source: Cyberdyne)

Although Fraunhofer is confident enough to go public with its work, a number of technical challenges remain. One is to work out what new safety challenges are posed by powered exoskeletons hefting large masses, and another is to make the suit more like enhanced personal protective equipment, and less like a scary, sci-fi appendage. Â

The construction versionÂ

A number of other products have already reached market, most in the medical field. US company ReWalk Robotics’ suit has been developed to allow paraplegics to walk again, and military manufacturer Raytheon has produced the XOS suit, which weighs 68kg and allows soldiers to carry an additional 90kg on a backpack. Â

Japan’s Cyberdyne has produced Hybrid Assistive Limb – HAL for short – which resembles a kind of wearable robot, and helps people with physical impairments move around.Â

So far only one suit has been developed specifically for construction and, oddly, it’s unpowered. Â

The Ekso Works Industrial Exoskeleton produced by American firm Ekso Bionics, uses a system of counterweights to allow a worker to heft heavy power tools as if they weighed nothing.Â

Loads are transferred through a carbon fibre harness to the ground, meaning that the suit bears the weight of the tool rather than the person inside it. Â

The counterweights then allow them to overcome Newton’s second law and move weights around with a fraction of the force than would otherwise be required.Â

By all accounts, the suit requires a bit of getting used to, and it is still a little way from reaching a builder’s merchant near you.

When it does, however, it may even have interchangeable arms depending on what kind of tool is being used.