Mongolia has made a request to join the developing northeast Asian Super Grid (ASG), a visionary plan to connect electricity systems In Russia, Japan, China and South Korea.

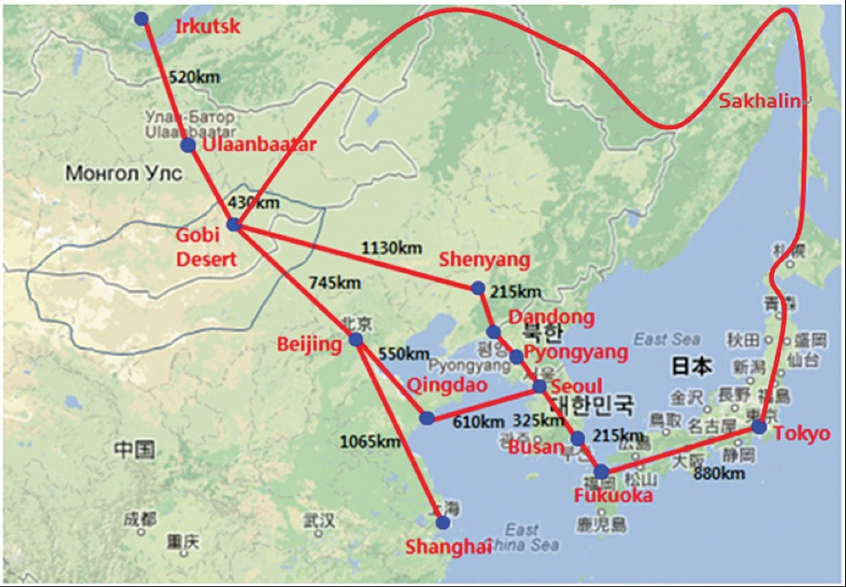

If it goes ahead the plan will create a ring of interconnectors with a diameter of some 2,000km, distributing to the region cheap power from Russia and Mongolia’s Gobi Desert.

Technology and peace are among the wider implications. The grid would provide a telecoms backbone for the region and lead to closer cooperation between the countries, thus reducing national animosities that began before the Second World War and still persist.

Mongolia’s request to join was made to Oleg Budargin, the head of power company Russian Networks (Rosseti), who has been meeting with Mongolian Prime Minister Jargaltulgyn Erdenebat and his energy minister, Purevzhavin Ganhuu. The negotiations concern Rosseti’s involvement in modernising Mongolia’s energy system, as well as Mongolia’s possible membership of the ASG.

In particular, the two sides discussed the construction of a 500kV high voltage direct current (HDVC) power line to link their grids and provide Mongolia with relatively cheap electricity. Rosseti noted in a press release that this interconnector would become part of the ASG if it goes ahead.

After Fukushima

The idea of a continental-scale ring-main was first put forward by Masayoshi Son, the founder and chief executive of Japanese telecoms giant SoftBank, who is also the richest man in Japan.

Masayoshi Son, the father of the Asian Super Grid

Son, 59, developed the concept after the Great Eastern Earthquake of March 2011 that killed about 16,000 people, led to the Fukushima Daiichi disaster and closed down the country’s nuclear industry. He also donated $120m to the victims and offered them his remaining salary until retirement.

So far, SoftBank’s renewable energy subsidiary, SB Energy Corporation, has developed 33 utility-scale plants in Japan.

Son believes the super grid would solve one of Japan’s most pressing strategic problems: how to provide energy security for a country that has high demand but declining coal reserves, limited space for onshore renewables, and faltering appetite for nuclear. Â

Countries with an energy surplus, such as Russia, would be attracted by the possibility of wider markets, whereas Mongolia would be able to import power more cheaply than it could generate it. For example, Rosseti estimates that Mongolia would pay half the price for Russian power than it would from a hydro scheme that it built itself.

First steps

The advantage of such a large grid would be to site renewable assets where there is most sun, wind and available land – one prime region being Mongolia’s Gobi desert.

The concept is similar to the idea of a European super grid that would put huge solar arrays in North Africa, hydro power facilities in Scandinavia and offshore wind farms in the northern North Sea.

Although the idea sounds attractive in theory, Son says he found it difficult to be taken seriously. Speaking in 2016, he said: “When I announced my idea five years ago, many people said it was a crazy idea, and they also said that it was neither economically nor politically feasible.”

However, when he talked to Liu Zhenya, a former chairman of State Grid Corporation of China (SGCC), he found that he had the same vision of an Asian super grid to distribute renewable energy.

So far, SoftBank has signed a memorandum of understanding with SGCC, Korean utility Kepco and Rosseti to study and develop the ASG project and update its progress. If Mongolia joins, its new signatory would be renewable power developer Newcom, which is partly owned by SoftBank.

Son envisages the first step of the ASG as a 400km HVDC link between Japan’s southern island of Kyushu and Korea.

One version of the grid, which includes North Korea in the mix (Nautilus.org)

It has been estimated that the cost of building the transmission infrastructure for the first phase of the grid, linking Mongolia, China, Korea and Japan, would be about $7bn.

Cho Hwan-eik, chief executive of Kepco, said in October last year that a feasibility study had begun on a project to create the first of these links between Korea, Japan and China. He added that this project would provide a cornerstone for the ASG.

If this project is successful, the grid would be extended to Mongolia, Russia and eventually India and Southeast Asia.

The consequences of a super grid

Rosseti Budargin has noted that the global demand for electricity is set to grow 30% between now and 2025, and that 70% of that growth will be in the Asia Pacific region.

The linkages may also help to overcome what former South Korean President Park Geun-hye called the “Asian paradox” – the persistence of political animosities despite the economic dynamism and growing interdependence between the main northeast Asian powers.

The power grid would require closer cooperation between governments, and would also foster closer economic ties based on clean tech manufacturing, a subject that is at the top of China’s economic and political agenda given the country’s problems with air pollution.

Australian political scientist John Matthews, writing in the Asia-Pacific Journal last year, notes that many of the territorial disputes between Japan, Russia, Korea and China concern the ownership of islands linked to offshore oil deposits. He suggests that the growth of clean tech industry offers the possibility defusing the disputes and providing players with compelling reasons to cooperate.

Top image: The Gobi desert, where Japan is looking for its future power (Severin Stalder/Creative Commons)

Further Reading: