For this Syrian city to heal, sensitive restoration is needed more than the amnesia conferred by gleaming office towers and shopping malls

Looking at the once beautiful city of our birth, Homs, Syria, we see a catastrophic loss of lives and mass destruction. Streets are jungles of ruins: broken minarets, shattered church bell towers and homes turned to rubble. Families are displaced and scattered. The chaos of the Syrian war has left deep wounds. Homs is not anymore the Homs we knew.

Among the people of Homs, however, despite this monumental loss and torment there are signs of healing, and of an inspiring desire to rebuild structures of life amid the ruins of war. Women are being helped to run small start-up businesses. There are efforts to rebuild partially damaged buildings, to care for orphans, and to rehouse internally displaced persons.

Efforts are underway at varying scales and on different aspects of restoring life. International groups are active, including UNICEF, UN-Habitat, the Danish Refugee Council, the Norwegian Refugee Council and the International Organization for Migration.

But local charities are active, too. One such working in Homs is Aoun, which means “support”. Aoun outreach volunteers literally map the urban destruction to prepare for reconstruction. “The old buildings that have been destroyed are priceless,” said Abdullah Al-Jundi, a final-year architecture student and Aoun volunteer. Neighborhoods with high numbers of displaced people are identified, and volunteers spend time with each family to listen to their stories and tailor support to match the urgency of need.

Other initiatives provide shelter for displaced people. One Homsian engineer we spoke to has been helping rehabilitate houses for the past three years. He believes it is important for people to return to their homes and neighborhoods quickly instead of living for extended periods with relatives or in public shelters such as schools. Only that way, he said, can viable communities take root again.

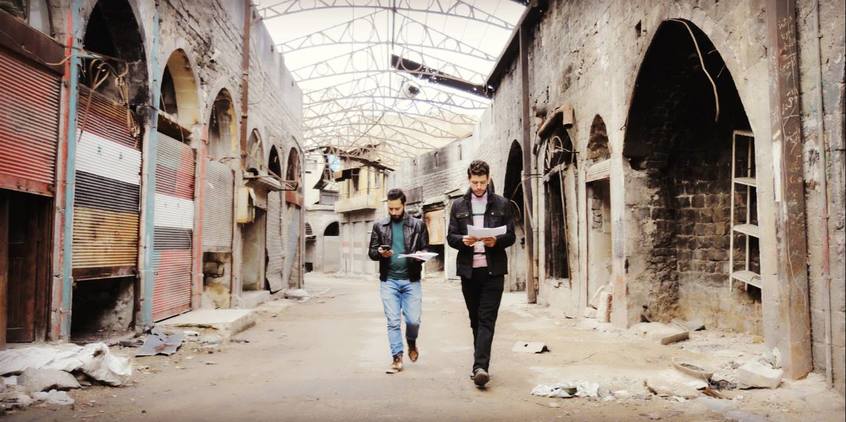

Architecture student and reconstruction volunteer Abdullah Al-Jundi, right, in a ruined souk in Homs, 2017 (Supplied by Ammar Azzouz)

“In the case of abandoned neighborhoods, we should focus on the rehabilitation of apartments that are near each other because the existence of citizens next to each other will be an encouraging element for people to return,” the engineer said.

“This small gathering will be the nucleus of return to the entire neighborhood, particularly if a medical clinic, a mosque and a church are rehabilitated in this nucleus. This will give returnees the courage and the sense of safety in their neighborhood.”

Loss to the world

Syria’s destruction is not just physical, but cultural. The ruin of religious monuments, houses, streets, schools and hospitals erased our richly layered past. These elements of the built environment have narrated our collective story as a nation – our desires, identities, interests and daily life – going back for thousands of years. As well as the fabric of cities like Homs, six UNESCO World Heritage sites in Syria have all been damaged or destroyed by the war. This destruction is a loss to the world, not just to Syrians.

“Heritage assets often embody meaning outside and above the fact that they are considered heritage objects by national and international bodies,” says Suzanna Joy of Arup, an international expert on archeological and cultural heritage. “They will represent a part of a person’s community which once destroyed is gone forever.”

In too many cases now, instead of a rich fabric with and around which communities live and evolve, we have only ruins and illustrations in history books.

Still, we must turn our minds to reconstruction. The most obvious thing to do is to observe history, look at contested cities where memory, power and identity were all in crisis. The processes of transition and transformation these cities been through will help us to understand what is needed to rebuild Homs. We should learn lessons from the past.

Learning from neighbours

Beirut, a neighbor to Homs, is one of these cities that was divided and exhausted by its war and then rebuilt. However, it is of vital importance to avoid the problems that the reconstruction of Beirut has created. Beirut’s reconstruction has been heavily criticised for creating new divisions and for ruining many still-standing buildings. Gruia Badescu of the University of Oxford explained that the reconstruction of Beirut’s city centre demolished 80% of the old building that were still standing at the end of the war. They have been replaced with modern luxury apartments, hotels, shopping centres and offices.

Abdullah Al-Jundi on visit to residents in Homs, 2017 (Supplied by Ammar Azzouz)

Critics commented that the reconstruction of Beirut’s city centre deleted parts of the past and the memory of the city which created a forgetful landscape. Aseel Sawalha researched the early responses of residents to the reconstruction of Beirut. In her paper, she provides different views towards the reconstruction, including Elias Khoury, a Lebanese novelist and journalist who wrote in 1995:

“Beirut attempts to regenerate itself by recycling garbage and destroying its own memories. The city centre appears as an empty space, a placeless space, and a hole in the memory. How are we to preserve the memory of this place in the face of such frightening amnesia?’

Mona Hallak, an architect and historical preservation activist, expressed similar feelings: “Downtown should have soul. It should be alive, but what we have is a culture-free ghost town for the rich.”

For the future of Homs, we need an inclusive city, a city for all of us. A city that brings Homsians together and create civic spaces for people from different backgrounds to mix, share their daily life and celebrate their city. This will foster togetherness and diversity. The reconstruction of Homs should also make Homsians create a sense of belonging to their city by building a collective memory. A well-established reconstruction should reflect the values of Homs and Homsians and through tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

Top image: Homs’s city centre before the war in 2009 (Source: Ammar Azzouz)

- London-based Syrian architect Ammar Azzouz is an analyst in the Programme and Project Management team at Arup, and a PhD researcher in the Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, University of Bath, UK. Abdalhamid Almasri is an architect based in Homs, Syria. Almasri has finalised his masters at Al-Baath University at the Department of Architecture, and is preparing to start his PhD in sustainability.