In the next 10 years, a new breed of super-hub airport is going to appear. It will be able to deal with half a million passengers a day, and it will form the centre of entire urban regions. This GCR special report looks at the surge in demand for air travel and gives an airport-by-airport guide to the largest 30 in 2030

Introduction

The most important fact to grasp about demand for air travel is that in the hundred years or so between the Wright Brothers’ Kitty Hawk and the A380, it has doubled every 15 years. This exponential climb rate will have to level off at some point, but the consensus among forecasters is that the global industry will grow by an average of 4.7% a year for the foreseeable future, which compounds to a 99% rise over 15 years. This means that the number of trips taken by plane somewhere in the world will increase from 6.3 billion in 2013 to something like 13 billion in 2030.

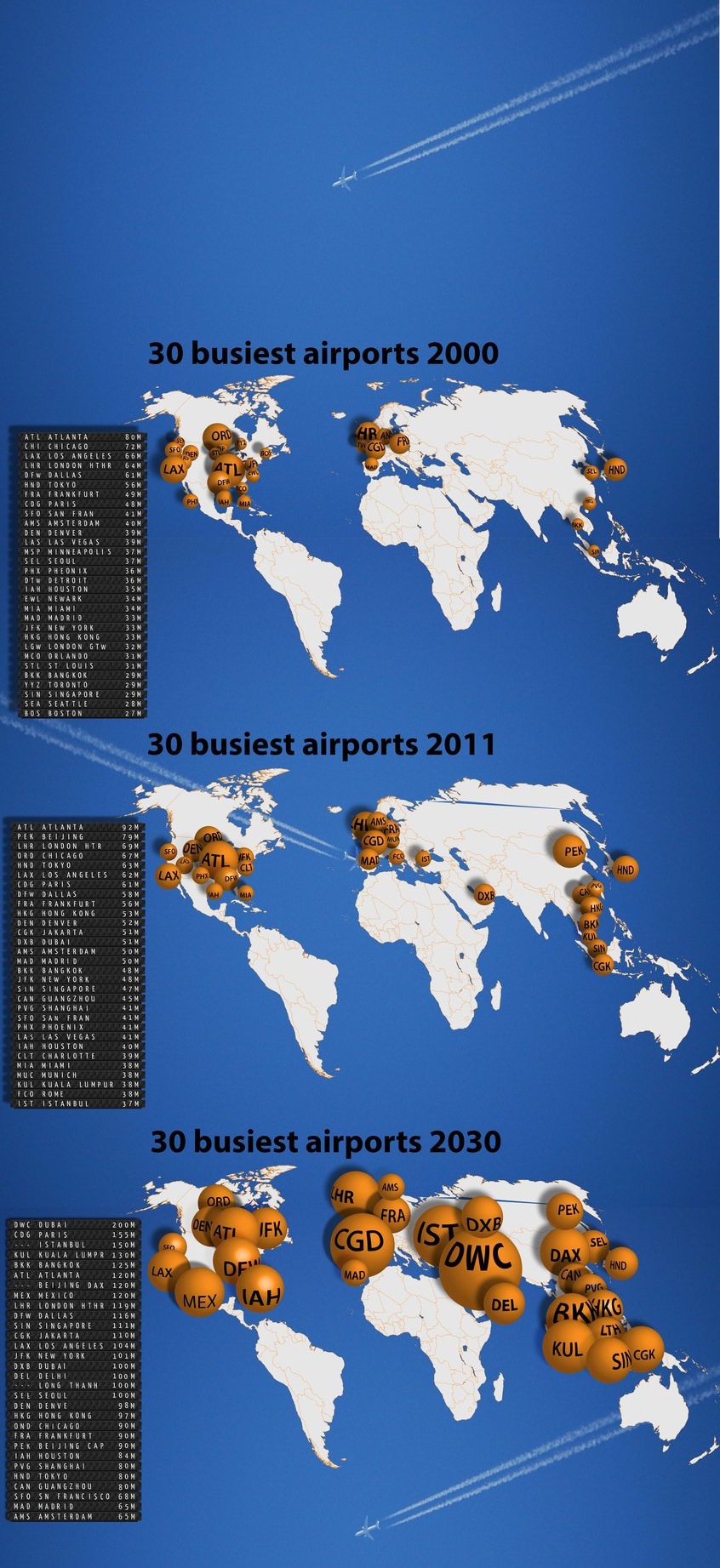

The 30 busiest airports in 2000, 2011 and 2030

The graphic is a statistical picture of the number of passengers who have and will use an airport. We have created a picture for the years 2000 and 2011 from Airports Council International statistics, and we have made an estimate of airport use in the year 2030 from a large number of other public sources. The result is something of a guess, but one based on present growth rates, the announced plans of individual airports and the forecasts of the many organisations that collect statistics on the aviation industry and use them to read the future: these include plane makers Boeing and Airbus, regulatory bodies such as the US Federal Aviation Authority and Eurocontrol (the European traffic control association), individual airport authorities, airport design specialists and the media (a list of sources is given at the end of this article).

The new breed of airport

What is clear is that the size of airports is going to increase to such an extent that they will transform the aviation industry. In the future, they are going to be immense: Beijing’s New International Airport, which has just started on site, will be bigger than the island of Bermuda. Denver airport (the largest in the US) controls an area of 140 square kilometres. They are also going to be the focus of intense economic activity. A second rank airport, such as Toronto’s Pearson International, is estimated to have generated $35bn (in US dollars) in 2012, or almost 6% of Ontario’s GDP, and to have created 277,000 jobs. By 2030 that figure is predicted to be $53bn. Pearson handles about 36 million passengers a year and exists in a mature economy. The impact of an airport such as Ho Chi Minh City’s Long Thanh, which is forecast to handle three times that number of passengers, and which sits in a developing economy, will be an order of magnitude greater.

This economic impact will be all the more if the trend continues to make airports into the centrepieces of their own urban districts: or, as they have become known, “aerotropoleis”. One striking example is Dongtan in South Korea, a new city built on an island, with private capital, which set out to appeal to those high-net-worth individuals who live within five hours’ flying time of Incheon airport – in other words, an exclusive international city, based on globalised industry, foreign universities and leading medical centres. Other airports in south-east Asia, such as Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi and, in the future, Long Thanh, are to become centres of “medical tourism” for a new kind of airmobile international consumer.

If these airports follow the pattern that everyone expects, they will be a visible indication of the seismic shift in economic power from Europe and the US to the Asia Pacific. It should be noted that just because everyone confidently foresees that this will happen, it doesn’t mean that it really will: there may be turbulence ahead, and national and regional economies are liable to perform all kinds of unexpected manoeuvres.

Nevertheless, for the purposes of this forecast we will follow the assumption given in the OECD’s Strategic Transport Infrastructures to 2030, that average global growth rates are followed in a linear way, although at greatly different linear rates in different regions.Â

Demand for airports

Xavier Huillard, Vinci’s chief executive, gave a press conference back in February that left no doubt about his enthusiasm for the building and running of airports. He said: “We want to capture the dynamism of global airline traffic, which is growing faster than GDP everywhere in the world and should double by 2030.”Â

According to the airport construction database of the think tank CAPA Centre for Aviation, there are something like $385bn of projects planned or in progress. Most are in Asia with just over $115bn of projects in train. China is the most active: by the end of next yearit will add 69 regional airports to the 193 that already exists. Other Asian countries, notably India and Indonesia, each with demand growth around the double digit mark, are lagging in the commissioning of new infrastructure.

The Middle East is undertaking major investment, notably in the spectacular $32bn expansion of sleepy Al Maktoum in western Dubai, but Saudi Arabia and Oman have also embarked on major development programmes. Meanwhile, airports are appearing outside the traditional centres, most notably Istanbul’s new facility, which is making claims to be the biggest in the world, eventually, and Mexico City’s recently announced facility, which is aiming at 120 million passengers on six runways – 120 million being, it would seem, the new normal for first rank airports.

More generally Airbus’ Global Market Forecast 2014-2033 says 42 of the world’s major urban centres are already “aviation mega-cities” and another 49 will join them over the next 20 years. Most will be in China: there are more than 50 urban centres in the world with more than 750,000 inhabitants that do not have an airport within 40km. Of these, 38 in China and seven are in India. Another key metric is given by the following chart:Â

Number of airports per million people:

- North America 2.5

- Europe 1.0

- Latin America 0.81

- CIS 0.67

- Middle East 0.50

- “Advanced Asia” 0.51

- “Emerging Asia” 0.39

- Africa 0.28

- China 0.13

- India 0.08

Source: OAG (formerly Official Airline Guide)Â

It is clear from this information that Asia in general, and China in particular, is going to be the location for tumultuous growth – always assuming, of course, there are no economic shocks waiting around the corner.

One caveat that should be born in mind is that predictions of airport use are prone to exaggeration. In the same way that historians of the 19th century used to measure a country’s power by counting the tons of steel it produced, modern commentators look at the demand for air travel and the activity at airports and draw conclusions about the vigour of a particular nation or regime. It is abundantly clear from reading media reports about who’s got bragging rights on the biggest terminals and the most passenger throughput that airports are a potent source of national and regional pride (as in the Telegraph headline from 1 October this year: “Dubai threatens Britain’s supremacy with $32bn mega-hub airport”). So there is an understandable temptation on the part of airport authorities to make bold claims about how much business they will be able to do in the future. Take the case of India, which had 75 million passengers in 2013. There have been widespread press reports that this figure will be more than 400 million by 2020, which would require a growth rate that increased from an average of 7.7% over the past five years to something like 50%; this is, if not flat-out impossible, then certainly fairly close to it.Â

Another factor to consider is that the greatest rise in air travel will not be international and it will not be undertaken in very large planes like the A380 – nor will it be out of very large hubs. Rather, it will be low-cost domestic flights in single-aisle twin-engine planes that take off and land in regional Indian, Indonesian or Chinese airports (the “point-to-point” market). In other words, the future of air travel is likely to follow the Ryanair model. By 2030, 70% of all flights will be in single-aisle planes and 40% of them will take off or land (or take off and land) within the Asia Pacific region (compared with 37% that do the same in North America and Europe combined). Much of the predictions about future air travel assume that the hub model will continue to prosper – very much the assumption that the new breed of mega-hub airports are relying on – but it’s quite possible that the airline industry’s business model may change over the next 16 years. Â

GCR’s guide to the largest 30 airports in 2030Â

Asia

Beijing CapitalÂ

This airport has become one of the first casualties of China’s 400% growth in air travel between 2000 and 2012. It was designed to handle 75 million passengers, but had to deal with 82 million in 2012, and is expected to be faced with 90 million in 2015. As with Atlanta, that’s a quarter of a million people a day who have to be administered, moved, fed and informed.Â

The airport is now at its maximum stretch, and this is in spite of the fact that back in 2005 it was fitted with Terminal 3, which was reckoned at the time to be the sixth biggest building on Planet Earth – 2km end-to-end. It was so big that it was split into three sub-terminals, which together processed 40 million people a year; it remained the largest airport building until Dubai International was constructed in 2008. Now it will have to continue until Daxing airport is built south of the city, after which it will be able to maintain itself at capacity. We are assuming it remains at 90 million in 2030.Â

Beijing DaxingÂ

Work has just begun on the international airport that is to become the Chinese capital’s main air terminal for the 21st century. It will be built about 46km south of the city, 30 minutes away from Beijing South rail station.Â

Most things about the new airport are still uncertain: estimates of how many runways it will have, and what its capacity will be by a given date vary from report to report. It’s not even clear whether it will be called Daxing (after the district where it’s located, which means “big prosperity”), Jingji (another place name), Lixian (“courtesy and virtue”), Yongding (the name of a river), Yufa (“elm soil”), Zhuque (“southern China”), or more prosaically Beijing New International. The price tag was reported as $10.9bn in 2011, when the project was first announced, but back in May that had risen to $13.7bn.Â

The best bet seems to be that when the first phase is completed in 2018 or 2019 it will have four runways and the capacity to handle 45 million passengers. By 2025, the airport aims to be able to serve 72 million passengers using six runways. At some time after that, it will have eight civil and one military runway, and will be able to process about 130 million passengers. If it does have nine runways, the airport could conceivably be expanded into unknown territory – some commentators have speculated that 200 million passengers might be possible, if demand justifies it. As with Dubai, Istanbul and Mexico City, this may make the airport into a test case of just how big a single facility can be before increased size leads to greater inefficiency. In practice it is not possible to say how big Daxing, if that’s its name, will be in 2030, but this article assumes that the 130 million figure is about right.Â

Shanghai PudongÂ

This is the maglev-enabled international gateway of the largest city in China. As with Daxing, it was built to relieve pressure on an established airport (Hongqiao). Construction work began in 1997 and ended in 1999. It now has three runways and two terminals, but in 2011 it received permission to build two more runways at a cost of a little more than $1bn. In April this year, it was decided to add a new storey to Terminal 1, thereby extending its floor area by 80% and increasing its capacity from 20 million to 36 million. There will also be a 500,000 square metre satellite terminal. By 2020, Pudong will be able to handle 80 million passengers, which is the assumption in the graphic. This is likely to be a conservative estimate of capacity by 2030.Â

Guangzhou Baiyun

The airport, which is located in the Baiyun (“White Cloud”) District of the Pearl River delta of south-east China, opened in August 2004 as a replacement for an identically named airport built in 1932. This $3.2bn facility is nearly five times larger than its predecessor, and by 2009 it was already the 23rd biggest in the world, with 37 million passengers a year.

As is the case with modern Asian airports, no sooner was it built than it had to begin rebuilding, and in August 2008 the airport’s expansion plan was approved by the National Development and Reform Commission. It includes a third runway, 3.8km in length, and a half million square metre Terminal 2, which together with the original building will create a space of 1 million square metres. Other facilities will include indoor and outdoor car parks, a transportation centre with a metro and inter-city train service.

The total cost of the expansion projects will be about $3bn, or only slightly less than the complex took to build in the first place. The third runway was completed earlier this year, although the terminal won’t be ready until 2018, by which time the airport will be able to handle 80 million passengers a year. As with Pudong, it is likely to have expanded again by 2030.

Chek Lap Kok (Hong Kong) (source: Foster and Partners)

Hong Kong Chek Lap KokÂ

When it was built in 1998, this airport cost $20bn, making it the most expensive in history – largely because it was sited on 12.5 square kilometres of reclaimed land and had the largest terminal building in the world. Its subsequent history is a testament to how quickly the sector is changing: it is already faced with the need to expand, and its terminal is now only the third largest (behind the terminal 3s of Beijing Capital and Dubai International).

The government of Hong Kong had been faced with a choice to improve its passenger handling systems and keep two runways or build a third on more land reclaimed from the South China Sea. In March 2012, it opted for the third-runway option: the extra expense of building on reclaimed land (which will have to be dredged from deep water) was compensated for by the fact that it was a way of acquiring 650ha of greenfield site in one of the most densely populated regions on Earth. The investment required was $11.1bn (at 2010 prices) between 2016 and 2030.Â

As well as the runway, there is to be a terminal and the associated apron facilities. With the third runway, Chek Lap Kok will – so the airport says – be able to “meet our unconstrained traffic demand and maintain our superior connectivity up to and possibly beyond 2030”. The stated capacity target for 2030 is 97 million and the likelihood is that with a general growth in demand of about 7%, this limit will be reached well before the target date. It is already the world’s busiest airport by cargo traffic. Â

Seoul Incheon Airport

Incheon has been somewhat eclipsed by the rise of Chinese and south-east Asian airports in the past 10 years, and even fell out of the global top 30 in the 2011 figures. The main reason for this was that the airport’s capacity was limited to 44 million, which is only enough for a place in the second rank in the new world of mass low cost travel and mega hubs. The government of South Korea expects demand for flights in Asia to increase by an annual rate of 6% in the coming years, compared with a world average of 4%; it is therefore eager to expand so that Incheon can try and attract those passengers. The longer term goal is to increase capacity to 100 million.

In 2009, the Incheon International Airport Corporation began design work on the $4.6bn third part of an expansion plan. The aim is to increase total airport capacity to 62 million by next year. After that, in stage four, it will expand its three parallel runways to five (one exclusively for cargo flights) and build four satellite concourses with 128 gates. At this point, it will have reached its 100 million passenger goal, and if that 6% growth projection is accurate it will then need to consider what might be involved in phase six.Â

Tokyo Haneda

Plans to expand Haneda International Airport are intended to be complete before the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics. Slot capacity is to be increased from 750,000 in 2014 to 830,000 by 2020, a railway line linking Haneda to Tokyo Station in 18 minutes is to be built, as is a road tunnel to cut connection time with the domestic airport of Narita. A third terminal for international flights and a fourth runway were completed in 2010, the latter on reclaimed land. This runway was designed to offer slots for an extra 60,000 overseas flights a year, which would increase Haneda’s capacity to about 84 million passengers a year. Construction work is likely to take 15 years and cost $5.8bn.

At the moment, it has little need of the extra capacity: demand increased only 11% between 2000 and 2011, and it now has one of the lowest runway utilisation rates in the region, with 101,000 movements per runway in 2013 compared with 180,000-200,000 at the bursting-at-the-seams airports of Jakarta and Beijing Capital. Nevertheless, it is competing with Beijing Daxing and Incheon Seoul as the gateway to North-east Asia, which looks likely to be one of the economic powerhouses of the 21st century, and it is a key partner for North American airports.

Another significant decision would be the removal of visa restrictions. A decision to relax the rules affecting Thai visitors led to an immediate surge in tourists from that country. How much greater will be the effect of a decision to do the same for Chinese visitors?

Looking at the longer term, by 2030, the Japanese government is planning to expand slots to 1.1 million by building a fifth runway and allowing new air corridors over urban areas (assuming quieter planes are available by then); using the new routes for three hours a day would add 40,000 landing and take-off slots at Haneda.Â

Although capacity at Haneda is likely to increase, we will assume that – as there is still no sign of a significant revival in Japan’s economic fortunes – growth at the airport continues at the rate of 7.5 million a decade. This will lead to a throughput of 80 million by 2030, which would push Haneda out of the top 10 international airports. Â

Bangkok SuvarnabhumiÂ

In December 2011, Airports of Thailand announced that it was speeding up the $2bn second phase of Suvarnabhumi’s expansion to 2016, one year ahead of its scheduled completion in 2017. The haste is an indication of the need to fight with rivals in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore for the role of leading south-east Asian hub.Â

The aim of phase two is to add a third runway, and enlarge existing domestic and international terminals. This would increase capacity to 65 million passengers a year, and would be undertaken in parallel with the construction of a $3bn domestic terminal that would be capable of handling 20 million passengers travelling within Thailand.Â

These two schemes are part of the overall airport enlargement that would increase Suvarnabhumi’s annual capacity to 125 million passengers – 90 million international and 35 million domestic – by 2024, at an estimated cost of $5.3bn. Â

Jakarta Soekarno-HattaÂ

This two-runway Javanese airport is proof that maximum capacity can be a misleading term: in 2010, total passengers reached 44 million, surpassing the 38 million capacity of its three terminals. In 2012, the airport was the ninth busiest airport in the world with 58 million passengers, a 12% increase over 2011, and in May 2014 it became the eighth busiest with 62 million passengers. The airport copes by getting the most out of what it has: there are 200,000 runway operations a year, compared with 101,000 at Haneda.

To alleviate the overcapacity, ground was broken at a new Terminal 3 in August 2013. The aim is to make Soekarno-Hatta into an aerotropolis that can deal with 62 million passengers a year by 2018. This is predicted to be complete by the end of 2014. A third runway is planned for 2015, and following that, work will get under way on a fourth terminal, after which the airport is expected to have a capacity of 87 million. By 2030, Indonesia is forecast to have the 10th largest economy in the world, and if Soekarno continues its 6.8% growth rate, it will be running just as much overcapacity as ever: we predict 110,000 million passengers a year in 16 years’ time.Â

Ho Chi Minh Long ThanhÂ

Vietnam is another country that is counting on a rapid expansion of its air infrastructure as part of a general modernisation effort. Up until now, Ho Chi Minh City has been accommodating international travellers at Tan Son Nhat, a former US army logistics base. As is often the case, an airport built in the countryside ends up imprisoned in the suburbs and unable to expand. The maximum capacity of Tan Son Nhat is 25 million passengers a year; in 2010 it handled only 15.5 million but with the annual growth rate of passengers reaching 15%, it will be overloaded by 2015. As Vietnam is experiencing a combined boom in tourists (increasing by 20% a year), babies (the population of 87 million is forecast to reach 100 million by 2020) and investment, it has been forced to build a greenfield solution: Long Thanh International Airport.

This $10bn facility will be situated about 40km north-east of Ho Chi Minh City. Work on the first phase is due to start in 2015 with a completion date set for 2020. A further two phases will run until 2030, after which it is envisaged that the airport will have four runways and terminals, and an annual capacity of 100 million passengers. The Vietnamese government has said that, at that point, the airport is intended to challenge Suvarnabhumi in Thailand and Changi in Singapore as the international hub of southeast Asia.Â

Kuala Lumpur International

KUL was opened in 1998 and is now Asia’s fastest growing airport, with a year-on-year increase of 19% between 2012 and 2013. If this popularity continues, it will reach its 70 million passenger capacity half way through 2015; the airport authorities are therefore in a great hurry to build and open terminals.

The airport is an illustration of two important points about building airports: one is that it is easy to make mistakes but hard to correct them. The other is that the single biggest factor in the Asia Pacific market is likely to be the growth of low-cost carriers (LCC). After it was opened, Kuala Lumpur suffered nine years of problems with its baggage system, eventually prompting a complete retender in 2007; other problems surfaced this year with ponding on runways, uneven parking bays and the revelation that plywood has been used as a base for asphalt. Despite that, the airport plans to increase its capacity to 75 million passengers by building a LCC terminal with a 30 million passenger capacity (this was budgeted at $800m but came in at $1.2bn). The final phase of the masterplan envisages the construction by 2020 of a fourth parallel runway and further satellite terminals, which would give the facility the ability to process 89 million passengers.

The expectation is that KUL will pass its great rival Changi before 2030; although it’s inconceivable that the 19% growth can continue, we expect KUL to add to its capacity at a constant rate of 20 million every five years, reaching a capacity and a passenger throughput of 130 million by 2030.

A380 at Changi Airport (Rolf Wallner/Wikimedia Commons)

Singapore ChangiÂ

A massive expansion of Changi International Airport is being planned. It includes a third runway and a fifth terminal, and will eventually double the hub’s capacity to 135 million passengers per year. The development forms part of a masterplan for the island announced last year by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

By 2020, a small military runway will be extended to become Changi’s third, and a fifth terminal will be built beside it by 2025. Almost 40km of taxiways will connect the area with the current airport. If we accept the forecast of the Singaporean government that passenger numbers will grow by 5% a year, Changi airport will be saying hello and goodbye to 111 million by 2030.Â

Delhi Indira GhandiÂ

India’s aviation market is still at a fairly early stage of development: the fact that there is only one airport for every 12.5 million people is an indication that hub airports will not be able to do their jobs until more “spokes” are built. Nevertheless, there are plans in hand to spend $4.8bn on an expansion of Delhi airport, with four more terminals by 2026 and a fourth runway by 2021. The work will go ahead when certain trigger points have been reached, in terms of passenger demand. When that happens, international traffic will be transferred to the new terminals, and the existing buildings will be dedicated to domestic traffic.Â

The Indian press has been talking about a rapid growth 360 million domestic and 90 million international passengers by 2020, making India the world’s third largest aviation market after the US and China. We are taking the view that it will achieve a 10% growth over the next six years – greater than its recent average of under 8% and close to the highest growth rates seen in other rapidly developing countries, such as Mongolia.

Dubai Intenational (Umair Shaikh/Wikimedia Commons)

Dubai International Airport

Dubai International Airport made the headlines in the UK in April this year when it overtook London Heathrow as the airport with the greatest number of international travellers. That success has been brought by the massive expansion of Emirates Air and its purchase of a fleet of Airbus A380s (it took delivery of its 50th back in July). The strategy, of course, is to operate as a kind of super-hub between the two worlds of Europe and Asia, and as such Dubai International plans to increase its passenger numbers from 60 to 90 million over the next four years, constructing terminal and concourse space that amounts to twice the size of Heathrow’s Terminal 5 (even though its third terminal is already the largest in existence – for now).Â

There is, however, limited opportunity to secure further growth – hence the construction of another, even larger facility. Â

Dubai World Central Al MaktoumÂ

Dubai will spend $32bn on expanding what is now its second airport to challenge for the title of the world’s largest. The project will comprise two phases. The first will take between six and eight years and will result in two terminals with a collective capacity to handle 120 million passengers and receive up to 100 A380s at any one time. Once that stage is completed, the airport will take advantage of its modular design to expand incrementally, which it is hoped will be an efficient way of delivering just-in-time capacity.

One issue that the client, Dubai airports, is alive to is that of designing IT systems and other business processes that can deal with this kind of unprecedented challenge. Paul Griffiths, its chief executive, told an air transport IT summit in Brussels a few years ago that DWC would have five runways and the capacity for 160 million passengers, but that “today’s processes and technologies are desperately lacking. They simply won’t work at that scale”. Those involved in designing, building and running airports will be watching how it is done at Dubai World.Â

Passenger numbers at Dubai are growing by 15% a year, which is enough to justify, for the time being, the faith that the government in placing in the airports sector. By 2020 Dubai’s planners hope that airports will support more than 322,000 jobs and contribute 28% of Dubai’s GDP. If growth does continue at a double-digit rate, both airports will be at capacity before 2030.  Â

Europe

London Heathrow

Heathrow has spent an average of $1.6bn a year since 2008 to upgrade all its terminals by the beginning of 2015, but terminals aren’t the main problem. One think tank described the UK’s approach to airports as “embarrassing”: at present, LHR is operating at something like 98% capacity, meaning a flight takes or lands every 45 seconds, but the authorities are still unable to decide whether or not to install a third runway.Â

The idea of an extra runway and a sixth terminal was suggested in 2009, but then dropped in 2010, after which little progress has been made in solving the problem of expanding the airport’s capacity. If a third runway is built, Heathrow says it will be enough for 740,000 flights a year, compared with 469,552 in 2013. Assuming the runway is constructed before 2030, that equates to an ability to deal with 119 million passengers a year. For the purpose of this graphic, we are assuming that Heathrow does reach that number of passengers.Â

Frankfurt International AirportÂ

This airport has always been in the running to become Europe’s largest, but it is likely to lose out to Paris in the next 16 years owing to the indifference of the German public to expansion, and the vehement opposition of those directly affected by it. Frankfurt suffered such a struggle to build its third runway in the seventies that it brought resident groups and environmentalists in to help plan its fourth. They opted for a 2.8km version rather than the 4km design that would have matched the other three. This would serve as a landing-only runway for smaller aircraft. The plan went into operation on October 2011. One particular advantage is that it will allow two simultaneous instrument landings, something that wasn’t possible before because the runways were not far enough apart: this small detail will enable the airport to increase its capacity from the current 83 to 126 aircraft movements an hour.

In 2009, the German government decided to create a third terminals for Frankfurt with the aim of bringing it up to 90 million passengers by 2020. The new terminal should be able to process up to 25 million passengers a year – again, very much the new normal for a first rank international airport. There, however, Frankfurt might stay, as further expansion will be difficult in the absence of a fifth runway.