It is now 11 months since Global Infrastructure Solutions (GISI) finalised its merger with US project manager Hill International.

The all-cash deal agreed last August valued Hill at £173m, although the emergence of a rival bidder pushed that price to $200m when closure was reached the following December.

Both sides had reason to be satisfied with the transaction.

GISI, which has its headquarters in New York, had taken another step towards world domination – or the “global diversification and expansion of its consulting platform” as the company’s press release phrased it. The deal was the fifth agreed in 2022, and its turnover is now set to rise considerably from the £12bn it reached in 2021.

For its part, Hill was able to free itself from the pressures and obligations that a listed company must live with. And as GISI’s business model is to leave its acquisitions essentially intact, it was able to retain its management and its corporate identity.

After the deal

To find out how the company has developed since then, GCR talked to Waleed Abdel-Fattah, president of Hill’s Middle Eastern and North African division.

Although Hill has 100 offices across 42 countries, its main geographical areas are the US, Europe and the North Africa/Middle East region. It is Waleed’s job to develop the business in the last of these, and although Hill may no longer have to meet the demands of analysts and shareholders, it does have to meet the expectations of GISI.

“They understand the industry and they want you to deliver,” Waleed says. “We have short and long-term targets. The model of GISI is that they keep every company with the same chief executive and the businesses keep their DNA, but there’s an understanding of the nitty-gritty of the businesses and we have to be up to speed. We are one of 39 companies, and they all have to be dancing in the same way.”

The new arrangement has other advantages. One is an ability to “tap into” resources or expertise in sister companies – Waleed gives the example of Hill’s cooperation with Australian project manager Palladium in the aftermath of September earthquake in Morocco.

Another is increased financial capacity, and it is Waleed’s main task to turn this into market share.

The big three

Fortunately for Waleed, the three of the large national markets in his area of responsibility are expected to grow rapidly. The most important is Saudi Arabia (KSA). Here the construction sector was worth a little over $133bn in 2022, and is forecast to expand by about 4% a year as the kingdom labours to achieve the goals set out in Vision 2030.

The second largest market is Egypt, a $47bn market now, but forecast to grow twice as quickly as KSA to reach $70bn by 2028. In third place is the UAE, $39b and forecast to grow at 5%.

Hill is a major player in all three of these markets. In KSA it is managing a number of megaprojects, such as the 50,000-unit city of Dahiyat Al-Fursan to the northeast of Riyadh, and the design and construction of lines 4, 5, and 6 of the Riyadh metro.

Other big schemes coming up include the long-awaited land bridge between Riyadh and Jeddah, which Hill is bidding for with Italferr, the consulting arm of Italy’s state-owned rail operator, and Spanish engineer Sener. This $7bn project will consist of six lines, 1,500km of which will be new and 680km upgraded.

Waleed says: “It’s been a long time coming, but now we’re on the ground. The Saudis have the funds, the route is clarified and there is technology to stabilise the sand. They have two options for a project team: they will either go with a Chinese-led consortium and a public–private partnership or they will put it out to tender.”

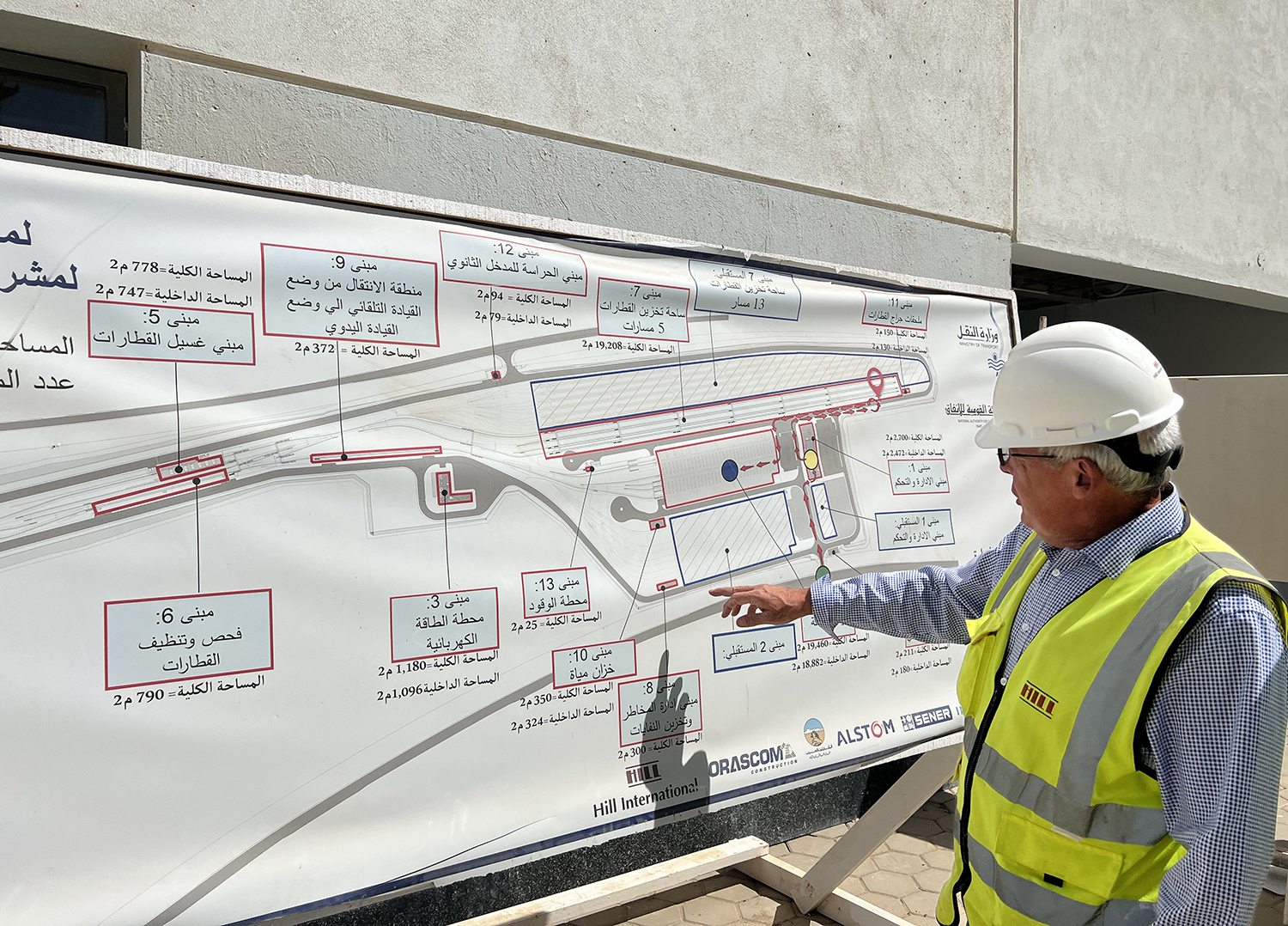

In Egypt, Hill has won a string of prestigious schemes, including the $1bn Grand Egyptian Museum, the $2.9bn Cairo monorail, the El Alamein tourist resort, the 3,200ha Madinaty tourist development, and is hoping to win the Terminal 4 project at Cairo International Airport and high-speed rail lines from Alexandria to Aswan and Luxor to Hurghada, among others.

Teamwork

Given that his company now has the financial backing of GISI and an active market, Waleed’s main job is to increase Hill’s capacity to take on work: to add to the “depth of organisation”, as he puts it.

He is able to move personnel around the region, pull others in from Europe and the US, and make use of existing teams. For example, the energy sector is being handled by teams in Greece and Cyprus. But there is also a recruitment drive. “We’re hiring new people for rail work and later healthcare, and I’m trying to build my own team.”

The result is that Waleed’s job has essentially become that of a football manager, training and selecting teams. “Sometimes personnel management is 100% of my job,” he says. “Winning work is not the major thing now – there’s a lot of work in the market – but delivering and making it happen are major issues.”

This teamwork can be difficult to establish. On the Cairo monorail, for example, there were 200 people in the project management office working with a French contractor and an Egyptian contractor – maybe 15 nationalities in all. “If you saw them in the first or second months, you’d get the feeling it’s not going to work,” Waleed laughs. “Now if you see them, they have become like a family.”

“In KSA, if they say ‘show me your A team’. They want to see them physically. A company is only as good as the team that it has on the job, so I want to have a core team that can react to these requests. I can’t have everyone sitting on the bench, otherwise I’m losing money, but I have to know key guys are available.”

So the aim is to build up a corps of project managers who carry the Hill DNA: who know the company’s practices and procedures and can establish a project team then stay with it until everything is working.

“We try to keep the core team together. It makes a big difference. The human factor. A good team will hit the ground running, they understand the company and they understand each other, they feel safe and secure and trust each other. Once you have that, you support them big time.”

As for recruitment, Hill’s offices in Dubai, Cairo, Athens, London, and the US are all looking for staff, with urgent demand met through agency hires. The headcount now is almost 1,800 and the aim is to increase that up to 30% before the year end, with most bound for Saudi Arabia.

Waleed says he looks for people who have a reputation in their corner of the industry, but also understand the region’s culture. “Someone may be the best in a sector, but they can’t communicate. As the lead guy, you need to be able to communicate and convince, and you need to give independent advice. We don’t want a yes man.”

Further afield

As well as the big three markets, Hill is looking at other countries in the region where it has a presence, but has yet to dominate. The more remote prospects are in sub-Saharan Africa, where Waleed admits to a certain “shyness”, but might consider a future venture into the eastern and southern regions.

The big prize is India. The market presently stands at $700bn and is expected to grow by 5% between now and 2027. So far, Hill has won roles on Line 4 of the Mumbai metro and the Indian Oil Corporation’s Technology Development and Deployment Centre in Faridabad, near Delhi.

“India is going to be big, but we need to approach it a bit differently,” Waleed says. “It has its own dynamics, so we need to be able to understand the market and we need a tailored solution.”

Hill’s main presence on the subcontinent is through Neyo Group, a cost consultant with around 300 employees that it acquired in August 2021. Waleed says Cairo HQ has been active in supporting this outfit and will engage more in 2024 once the expansion drive in the Middle East has died down and that region can be put into “auto-pilot mode”.

He says: “I hope that next year will be the year of India. I need to have a deep dive. I think infrastructure will be the easiest sector for us, that includes railways, airports.”

He adds that there is a lot of Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) money in India, and Hill has a history of working with JICA, especially on the Grand Egyptian Museum. What’s more, Hill recruited a lot of Indian workers on the Cairo monorail, and they could have a part to play in future projects closer to home.

Last but not least: Libya

The Libyan market is the mirror image of India, in that Hill used to be a major player, and retains an institutional memory of its projects, but was forced to shut them down after the 2011 war broke out.

Back in 2008, the company won a £5bn deal to build college campuses across the country, and by all accounts this was a happy experience for the staff who were assigned to it. Waleed says the people who worked on the Tripoli University scheme in particular “keep banging the door” in the hopes of a return to the country.

They may get their chance. Waleed says Hill opened an office in the country in 2007 and has managed to keep it open all through the disasters that followed the Nato intervention. There is electricity throughout the day and life in Tripoli has returned to normal. “I usually visit in September,” Waleed says. “You go out, have dinner, there’s a summer festival. It’s a regular city.”

“I’m not going to say everything is rosy, but we’ve gone back to our old project at the University of Tripoli and we’re working on a ring road.” The deal for this, which is worth somewhere north of $1bn, was signed in March, and Hill has a team of around 40 working with a coalition of Egyptian contractors.

As well as benefiting from the cessation of hostilities, this project may go some way to making that cessation permanent. “People can go every morning and they can see that something is happening,” Waleed says. “It makes a difference to see contractors on the ground, moving dirt. It will improve the life of everybody in the city. They’re trying to push health and education now, but it’s still at an early stage.”