It’s a small step, but it could start an incredible journey.

Today, the ministerial council of the European Space Agency (ESA) said it would proceed with a feasibility study into space-based solar power (SBSP) generation.

The decision, thrashed out among ESA member-country ministers over 22-23 November in Paris, means SBSP is now formally on the ESA’s strategic agenda.

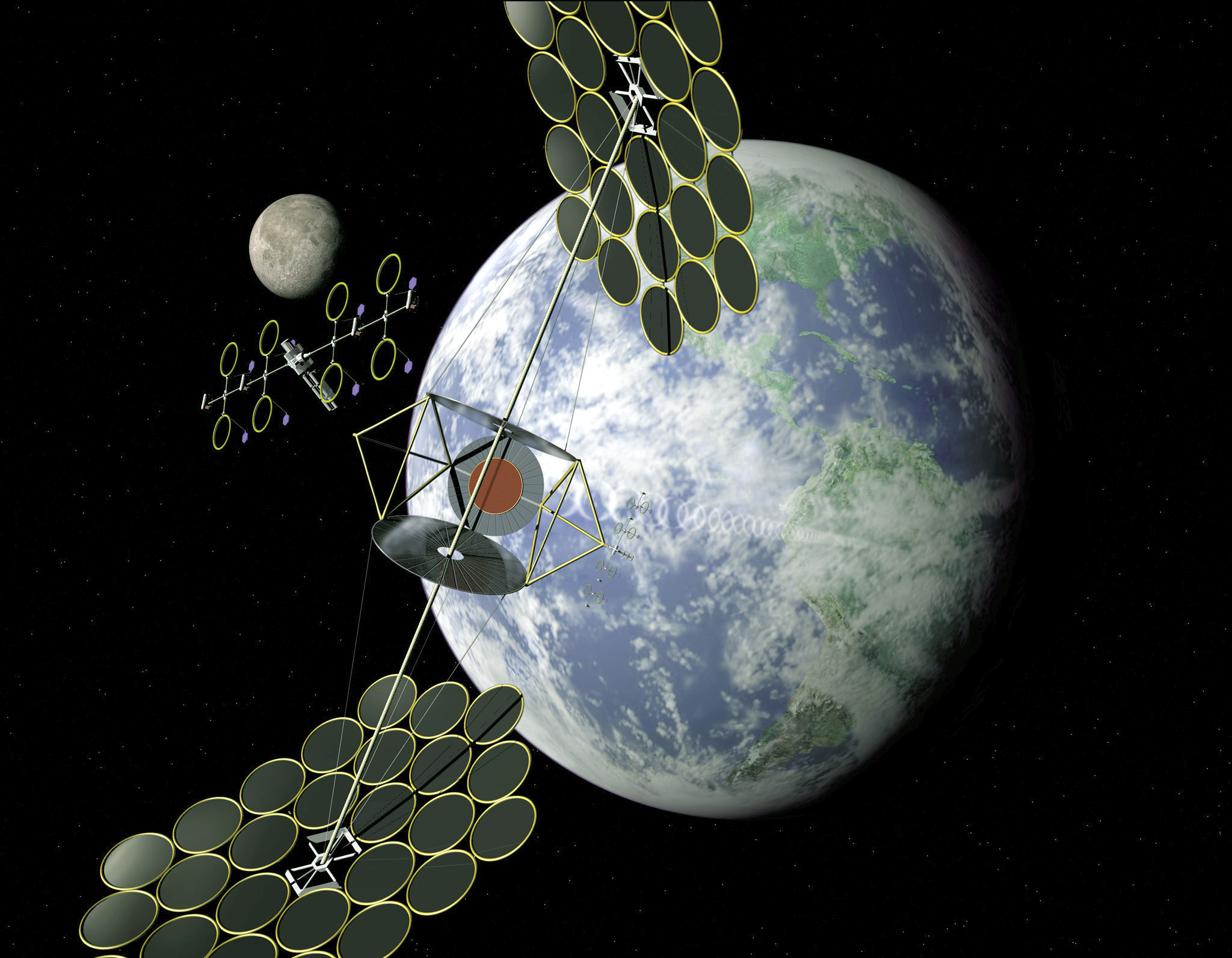

The idea is eventually to launch big solar-farm satellites into orbit around Earth so they can harvest the Sun’s energy outside Earth’s atmosphere, where it’s more intense, and beam it wirelessly to receivers on Earth.

The ESA says that, theoretically, SBSP could provide stable baseload power to European grids the way nuclear, hydro, coal and gas plants do now.

“If this works, if we could establish a solar power plant in space in the order of gigawatts – this is the order of magnitude we are aiming at – and use this sustainably on the ground, it would be a huge game changer,” ESA director general Josef Aschbacher told a live streamed press conference today.

Tentative steps

Today’s decision approves preliminary research on the technical, political, and economic viability of the idea ahead of the next ministerial meeting in 2025, when a decision whether to launch a full development programme will be on the table.

The idea has been around for decades but recent events, including the climate crisis, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and a dramatic drop in the cost of heavy orbital launches, has propelled it to the fore.

In August, ESA published two cost-benefit studies it commissioned from consultancies in the UK and Germany.

They concluded that SBSP could provide competitively-priced electricity by 2040, displacing fossil-fuel sources of power and reducing the need for large-scale storage solutions.

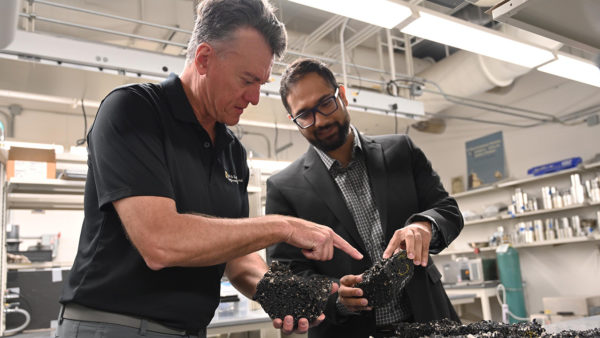

The biggest technological hurdles they identified included the assembly by robots of the solar arrays in space, the wireless transmission of solar power over thousands of kilometres, and the availability of a competitive and reliable space launch market.

Separately, the US, China and Japan are reported to be exploring SBSP. The UK, an ESA member, allocated £3m for SBSP research in July.

Twenty-two countries are members of the ESA, which is independent of the European Union.

ESA member-country ministers meet every three to four years to agree the body’s priorities and commit their countries’ funding.