9 May 2013

A media backlash against Chinese-built facilities in Zimbabwe reflects deep fault lines in the country’s fragile political equilibrium, and presents a conundrum for China, Rod Sweet argues

“Zimbabwe is losing millions of dollars to the Chinese in untendered government projects…”

So began a blistering attack – billed as a news report – against construction projects awarded by the Zimbabwean government to Chinese companies in this week’s edition of the privately-owned weekly, the Zimbabwe Independent.

The article catalogued a list of grievances that have been aired with growing frequency in recent months by the country’s emboldened media.

Grievances include allegations of poor workmanship, structural problems, opaque procurement processes, inflated costs, and the flouting of building and environmental regulations.

Projects cited include roads, airports and dams, plus the National Defence College and the controversial Long Cheng Plaza hotel and shopping mall under construction now in the capital, Harare.

A number of local engineers, all but one quoted anonymously, complained that the projects were delivered in a way that seemed to be above of the law.

“Any construction that goes on without adhering to council by-laws is an illegal structure,” one engineer said. “The building codes and construction standards laid out by the Standards Association of Zimbabwe (Saz) must be adhered to. Any violation should meet the full wrath of the law.”

Other media have weighed in with similar criticisms.

In February the Zimbabwe Mail & Guardian reported that four engineers, all inspectors from the ministry of public works, had the previous July been forced off the site of the new National Defence College, which was being built by Chinese contractor Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group and was financed with a loan from China.

The inspectors told the newspaper that the contractor, backed by soldiers from the Zimbawean army, made them leave after they raised concerns during an inspection over the “design of the buildings, the quality and quantity of material used and issues to do with the foundation”.

The inspectors asked not to be named, but Ben Rafemoyo of the Engineering Council of Zimbabwe, vented his anger openly: “Our counterparts from Eastern countries are operating above the law because they say they are part of government-to-government agreements,” he told the Mail & Guardian.

Another flashpoint is the Long Cheng Plaza shopping mall and hotel complex.The $84-million project is backed by diamond-mining giant Anjin Investments, which, according to China’s Xinhua news agency, is a 50/50 joint venture between Zimbabwe’s state-owned Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation and the contractor mentioned earlier, Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group.

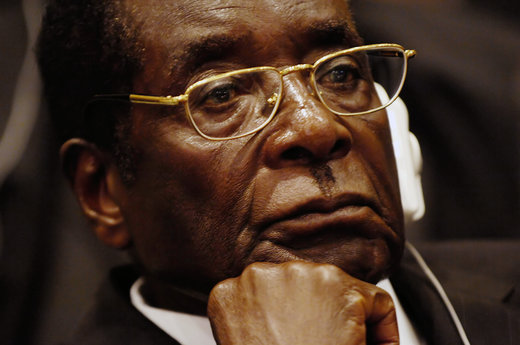

Zimbabwe’s president Robert Mugabe will go to the polls again on or after 29 June. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Media outlets such as the Mail & Guardian, and another Zimbabwe newspaper, The Daily News, have slammed Long Cheng Plaza because it is being built on a wetland and has been condemned by Zimbabwe’s Environmental Management Agency, a statutory body.

In an angry article in January this year The Daily News claimed that the plaza, reportedly under construction by the Anhui group, is being built under military guard. This, it said in sarcastic indignation, “could be a first for commercial assets in Zimbabwe”.

The paper concluded: “the Asians have become untouchables in Zimbabwe.”

Conundrum

Before the power sharing agreement between long-term president Robert Mugabe and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai took effect in February 2009, such criticism of the government’s policy of getting facilities built by Chinese companies, and paid for with loans from China, would likely have been impossible.

While the media backlash reflects greater press freedom, it also shows how construction is now in the firing line of Zimbabwe’s febrile politics, and creates a conundrum for Chinese contractors and financiers who claim to operate under China’s strict policy of non-intervention in a country’s internal affairs.

Complaining of being kicked off the National Defence College building site, a source in the public works ministry told the Mail & Guardian that the Chinese “are too powerful to control as they seem to have a network of powerful political connections”.

The newspaper also notes that under the 2009 power sharing agreement, public works is headed by Morgan Tsvangirai’s party, MDC-T.

The conundrum for companies like Anhui is, what if the government China did the deal with splits, and a significant segment of the population of the country resents the deal?

The issue will become more acute in Zimbabwe because the country’s fragile national unity government faces a critical test within months.

The current parliament reaches the end of its constitution-set, five-year life span on 29 June. After that, bitter political foes, Mr Mugabe and Mr Tsvangirai, go back to the polls.

Prospects for a smooth, peaceful and decisive election appear optimistic at this point. Support among the population for Zanu-PF and MDC-T seems evenly divided, and already the two sides are warring over when the elections will be held, with Mr Mugabe demanding a snap vote on 29 June, while Mr Tsvangirai is lobbying for a delay so that constitutional reforms agreed in 2008 can take hold.

Think tank the International Crisis Group has raised the possibility of disputed polls or even a military intervention by the state’s security apparatus, which has benefitted from 33 years of Mr Mugabe’s rule.

In Libya, thanks to the civil war, firms from China and elsewhere in the world had only one choice: get out fast.

Zimbabwe could present a much more complex challenge.