18 March 2014Â

Thanks to a Chinese company’s approach to management and a €280m expansion plan, Greece is getting pulled up by its Piraeus, reports David Rogers.

The year-end figures for Europe’s ports show that most have still not shaken off the effects of the recession.

Last year, Rotterdam lost 1.7% of its business and Antwerp declined 0.7%. But the Greek port of Piraeus reported an extraordinary 20% increase in business. It is now three times greater than it was four years ago.Â

Piraeus was once best known in the shipping world for industrial disputes and low productivity. Then in 2010 one of its two container piers was taken over on a 30-year concession by the Chinese shipping giant Cosco Pacific.

The concession cost €50m and, as part of the deal, Cosco agreed to build a third pier. So now it is spending more than €280m to expand and modernise its dock to handle up to 3.7m containers in the next year, which will make it one of the world’s 10 largest ports.

Captain Fu Cheng Qiu, who is running Cosco’s operation at Piraeus, told The New York Times recently: “Everyone here knows that you must be hard-working. The Chinese want to make money with work.” By contrast, he says many Europeans “wanted a good life, more holidays and less work. And they spent money before they had it. Now they have many debts.”

One element in the state-owned Chinese company’s success has been to increase labour productivity and reduce costs. The New York Times reported that some workers on the Greek pier were paid $181,000 a year with overtime, whereas Cosco is typically paying less than $23,300.Â

On the Greek side of the port, union rules required that nine people work a gantry crane; Cosco uses a crew of four.

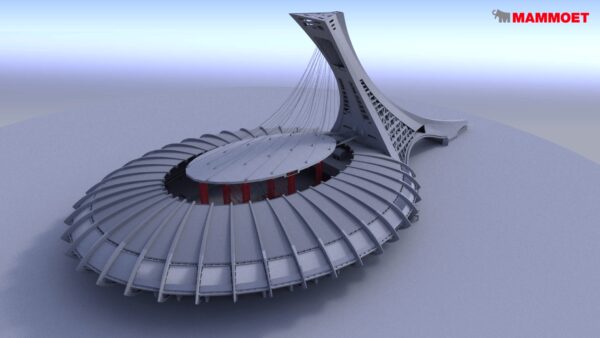

The port of Piraeus, which is on course to become one of the biggest in Europe (Nikolaos Diakidis/Wikimedia Commons)

The development of the port as a logistics hub for south-east Europe is an important part of the Greek government’s plan to bring its economy out of its six-year recession, cut the country’s 28% unemployment rate and wean itself off the $329bn of international emergency aid it presently receives to stave off bankruptcy.Â

In a roundabout way, the Piraeus development is also part of the European Union’s plan to relieve the pressure on the road network in northern Germany and the Low Countries.

Seventy-four per cent of all the goods entering or leaving Europe go by sea, and although the continent has about 1,200 ports, one-fifth of its freight passes through just three of them: Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp.

The European Commission has said this creates “huge inefficiencies” as a result of longer routes and greater congestion in the ports’ hinterlands. And this problem can only get worse if, as predicted, the amount of cargo handled by Europe’s ports grows 50% by 2030.

The latest “ultra large container vessels” that ply the Asia-Europe route carry up to 18,000 containers. Placed on trucks they would stretch from Rotterdam to Paris.

To make sure this never actually happens the commission wants to improve facilities and transport links at 319 other ports along Europe’s coastline, and the example of Piraeus is showing how this can be accomplished.