China has yet to release promised funding for two major railway projects in Nigeria, reports the South China Morning Post.

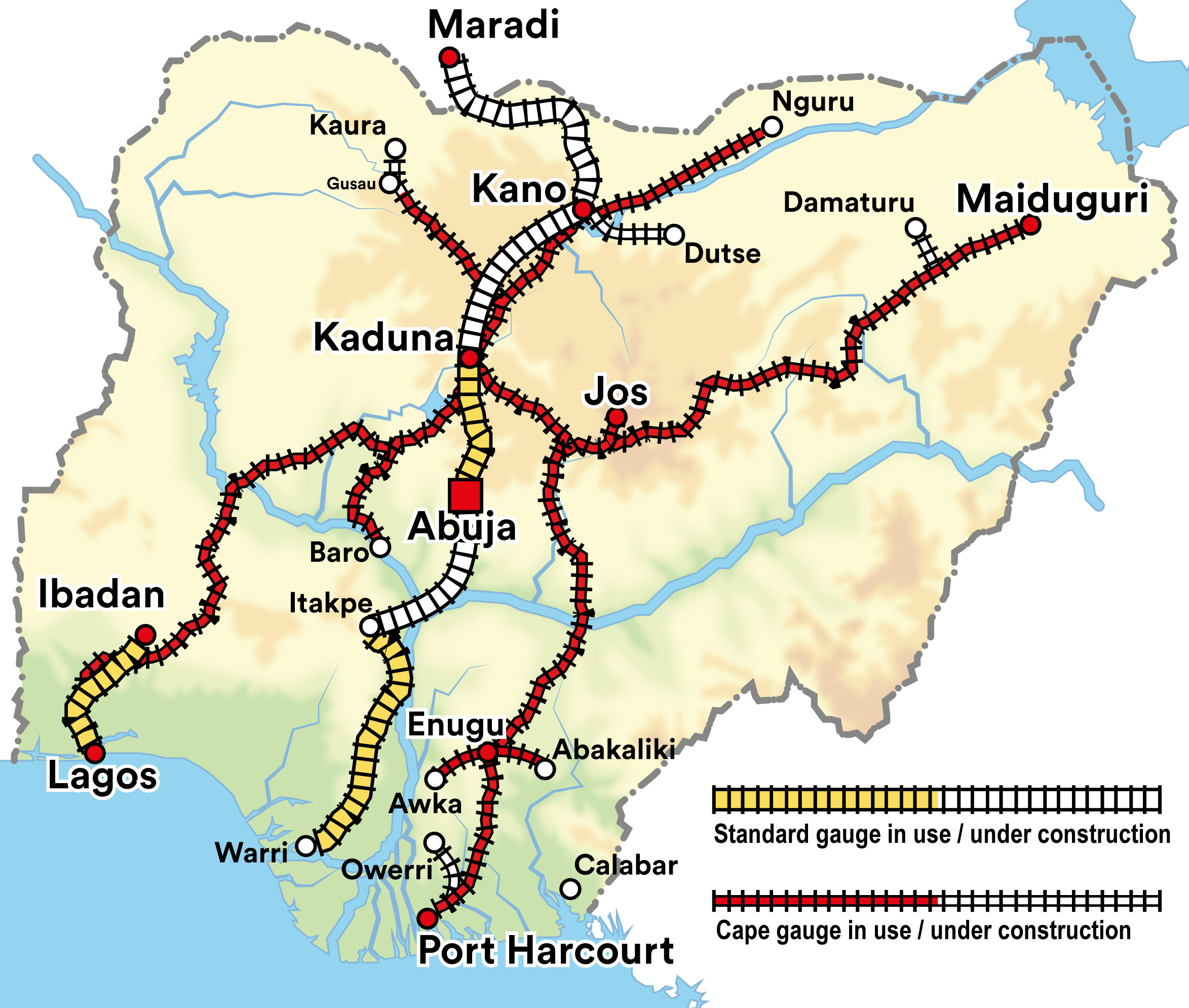

GCR reported in January 2021 that Nigeria had been waiting a year for 85% of the funding for a $5.3bn railway from Ibadan in the south to Kano in the far north, which it expected as a Chinese government loan.

It now appears that no progress has been made since.

A second rail scheme hit by China’s failure to disburse a loan is the $3bn reconstruction of a 1,000km rail line between Port Harcourt on the Atlantic coast and Maiduguri on the border with Chad.

In both cases, Nigeria has supplied 15% of the project funding, allowing China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation to begin laying track. Unless China does provide the loans, however, the work will only continue if the Nigerian state continues its funding or succeeds in finding finance elsewhere.

Mu’azu Sambo, the Nigerian transport minister, commented at the weekend: “The Abuja–Kano and Port Harcourt–Maiduguri projects are ongoing but there is the challenge of the 85% foreign loan yet to be secured. We have been driving these two projects solely through appropriation, which is part of the 15% which Nigeria is supposed to contribute,”

He added: “Until we have the 85 per cent component, the project will have to be continually funded through the appropriation.”

BRI scales back its ambitions

China’s failure to provide the loans seems to indicate a reduced appetite to fund commercially risky projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In the wake of the Covid pandemic and the continuing war in Ukraine, a number of African countries have been struggling to service their debts.

In 2020, sub-Saharan Africa had a total external debt of more than $700bn, compared with $380bn in 2012. The amount owed to official creditors, including multilateral lenders, governments and government agencies, increased from about $120bn to $258bn.

Doubts over the sustainability of this debt burden led the Chinese government to announce in August that it had forgiven 23 loans to 17 African countries, and that followed an earlier cancellation of at least 94 interest-free loans to African countries amounting to over $3.4bn, between 2000 and 2019.

A recent survey by Chatham House noted that Chinese authorities are now seeking greater control over infrastructure finance. “Loans are generally on a smaller and more manageable scale than before, and ambitious strategic visions of linking central Africa to the BRI via integrated transport corridors appear to have been abandoned,” the UK think tank said.

This suggests a move from grand projects such as Nigeria’s north–south lines to smaller schemes that are more likely to turn a profit in a shorter time.

Addressing a BRI symposium last November in Beijing, Chinese president Xi Jinping said that high-quality “small and beautiful” projects, which are environmentally and commercially sustainable and improve people’s livelihoods, should be a priority.

And the South China Morning Post quoted Ms. Yun Sun, head of the Stimson Centre’s China programme in Washington, as saying China had been cutting back on lending for some time. “Especially for countries already in trouble on debt sustainability, the Chinese have tightened up the wallet.”

She added: “Exim Bank does not provide free grants, it gives out loans. If China is not certain that the loans can be repaid, the disbursement decision will not be supported.”

However, the paper also quoted Tang Xiaoyang, an international relations professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, who said he did not think there had been a change in China’s lending policy, which supports financially healthy and economically productive infrastructure projects.

He said that the so-called loan promises were probably made informally rather than being legally binding agreements. “If contracts are signed, Chinese banks and companies usually implement them according to the terms and will pay the compensation if changes are needed,” he added.

Further reading: