A number of factors are coming together to propel the container port market along the west coast of Africa between the two desert states of Mauritania in the north and Namibia in the south.

Firstly, as with East Africa, those former European colonies with oil and strategic minerals to sell have become coupled to the Chinese locomotive. Although this has been something of an exchange of masters, the switch has begun to free some countries from their neo-colonial roles in the global economy, and introduced the kind of investment capital that Africa has historically been unable to accumulate or obtain from world financial markets. Much of this money has gone into providing essential infrastructure, including container terminals in new deepwater ports, and their hinterland road and rail systems.

Secondly, the change has sparked economic growth throughout the region, albeit from a very low base. According to World Bank statistics, the GDP of Nigeria, the regional superpower, declined from $62bn in 1980 to $46bn in 2000, before rising to an astonishing $568bn in 2014 (current US dollars, not adjusted for inflation). One measure of the western region’s dynamism is the growth in demand for construction services. Between 2013 and 2015 the total value of projects more than doubled in West Africa, from $49bn to $116bn, according to Deloitte, an accounting firm, while in East Africa total project value fell from $68bn to $58bn. (With oil and commodity prices beginning their precipitous slide in mid-2014, it remains to be seen whether this high-growth trend continues.)

Thirdly, governments in the region have moved to the landlord model of port operation. Instead of building and running ports themselves, they’ve taken to selling long-term concessions to big international port operators who, eager to stake a claim in the region, undertake to build and operate the ports for a few decades – thus recouping construction costs – before transferring ownership back to the host government. Hence, build, operate, transfer (BOT) is the most common form of procurement now. This has made the latest equipment and automation systems widely available for the first time. When they are built, West Africa’s new ports will be as good as any in the world.

Finally, the shipping lines are taking advantage of the appearance modern deepwater terminals to assign larger and larger ships to their West African runs, a process known as “cascading”. As Ultra Large and New Panamax vessels are added to European, Asian and North American routes, they displace the smaller vessels to lower volume markets. Lloyd’s List Intelligence (paywall) data shows that in just the one year between January 2013 and January 2014, the average size of container ship plying the Asia to West Africa run increased 38% to reach 4,178 teu. They continue to grow: in 2015, the giant Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) made news in shipping circles by adding Post Panamax vessels as large as 6,500 teu to its Africa Express service. One analyst was quoted by Lloyd’s as saying it would have been “unthinkable” a few years ago.

This means that any country that doesn’t expand its port will be forced out of the game – hence the rush to dredge access channels, deepen and extend berths and fill the quays with gantry cranes.

So, what new ports will this cascade of Post-Panamaxes be calling at? In order of advertised capacity, they are:

Tema, Ghana: Comparable to England’s Felixstowe

- Projected capacity: 3.5 million teu

- Draft: 19m

- To be completed: 2019

The ships calling now at Tema are half the size of the ones that serve Europe and Asia

Tema Port handles 69% of Ghana’s trade, but only with difficulty. The harbour is too shallow, the port equipment dates to the 1960s, there is insufficient gate capacity, too little warehouse space, too few cranes, and a lack of high-capacity roads out of the port area. Understandably, the Ghanaian government worried that the port would lose traffic to the Lomé Container Terminal in Togo, the first of the new generation of terminals to open (see below), as well as its most direct competitor, Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire.

In June 2015, a deal was finally closed between the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority (GPHA) and a joint venture between Bolloré of France and Dutch operator APM Terminals (APMT), called Meridian Port Services. This will secure $1.5bn to fund an expansion and modernisation project that will deliver the largest port in the region, by container capacity.

The work, which will be carried out by China Harbour Engineering and supervised by Aecom, will involve dredging a 19m-deep access channel and adding four container berths. The quay will be extended to 1.4km and a 4km breakwater will be constructed. In the hinterland, a six-lane highway will be built between the port and Accra, and rail infrastructure will be upgraded.

The planned port has a large capacity, comparable to England’s Felixstowe, the port that handles 42% of the UK’s containers.

This means that if the region’s economies continue to grow at their present rate, it will be the last to require further expansion.

Lekki, Nigeria: Breaking out of Lagos

- Projected capacity: 2.7 million teu

- Draft: 16.5m

- To be completed: 2019

The Nigerian Port Authority looks at a scale model of the port, designed to escape the city

The largest container terminal in Nigeria now is at Apapa in the Port of Lagos Complex, which is expected to have a throughput of 1.5 million containers in 2016. The problem with this facility is that it is in the wrong place – the suburb of a sprawling megacity with a metropolitan population in the region of 21 million. It is a classic problem: cities develop around a port, but then the port grows, leading to a crunch of interfaces and snarled traffic. APM Terminals, the Dutch port operator, has predicted that Nigerian box volumes would outstrip ports capacity by 2017, so Lagos could become a bottleneck for the entire region if nothing is done.

Lekki is the solution. This $1.5bn port will be located at a deepwater harbour 65km to the east of Lagos, and will be able to berth Post Panamax vessels of around 10,000 teu. When completed in 2019, it is expected to have a capacity of 2.7 million, about the same as Yokohama in Japan.

The concessionaire for the 90ha project is Lekki Port LFTZ Enterprise, a special purpose vehicle owned by Singaporean conglomerate Tolaram Group (62%), the Nigerian Port Authority (20%) and the Lagos State Government (18%). Lekki Port is developing the scheme on a build-operate-transfer (BOT) basis. It will have three terminals, one for liquids, one for dry bulk and one for containers, which will be sublet to Filipino operator ICTSI and France’s CMA CGM.

Haresh Aswani, the managing director of Lekki Port, has made expansive claims about the effect the project will have on the wider economy. He puts the direct and indirect economic benefit of the port and its surrounding free-trade zone at a whopping $361bn over the 45-year term of concession. It is forecast to contribute more than $200bn to the government exchequer and create close to 163,000 jobs by stimulating industrialisation.

This is probably a best-case scenario, particularly when it comes to government revenues – firms who set up in the free trade zone will not be paying any federal, state or local taxes and will be free to repatriate all their profits. Nevertheless, even less spectacular results look like value for money given the low cost of the infrastructure in comparison with long-term benefits for the national economy.

Lomé, Togo: Big port, little country

- Projected capacity: 2.2 million teu

- Draft: 16m

- To be completed: Unloaded first customer on 30 December 2014

Work under way on the Lomé terminal (Hill International)

This $380m deepwater container port in the Togolese capital of Lomé is the biggest infrastructure scheme in that country’s history, and represents a bold attempt to become the transhipment hub for all the ports in the region too small to take the Post Panamaxes. The stakes could hardly be higher: Togo’s nominal GDP is 2015 was only $4bn, and the economy is dominated by subsistence agriculture. The port therefore represents an immense investment, and looks set to be the most modern and dynamic element in the entire economy – if all goes to plan.

The signs so far are encouraging: Geneva-based MSC, the second largest shipping company in the world, decided in late 2014 to consolidate all its Asia-to-West Africa volumes at Lomé, for the simple reason that it was the only port able to handle vessels of up to 14,000 teu. The company’s African Express line now runs from Tianjin to Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Durban, Cape Town and Lomé, before heading back to Tianjin.

The work was carried out by Grupo Cyes of Spain and Somague of Portugal, and the expanded port is run by Lomé Container Terminal, which was set up as special purpose vehicle by Terminal Investments, a port operator owned by Dutch company Global Container. In September 2012, the Hong Kong’s China Merchant Holdings took a 50% stake in the venture, and a number of its staff joined the operational team.

The key to getting the project going was a $270m debt package from the International Finance Corporation, which is the part of World Bank Group that promotes private sector investment in developing countries. It arranged and led a consortium of financiers that included the African Development Bank, as well as German, Dutch and French institutions and Opec’s Fund for International Development.

Abidjan II, Côte d’Ivoire: The “lung” of the economy

- Projected capacity: 2.1 million teu

- Draft: 18m

- To be completed: Early 2018

The port handles 91% of Côte d’Ivoire’s trade

The government of Côte d’Ivoire really had no choice but to borrow the money to pay for its share of the work expanding the port at Abidjan because 91% of Côte d’Ivoire’s trade passes through it, generating 85% of the country’s customs revenues, prompting Chinese media to call it the “lung” of this poor country’s economy.

So the government secured a loan from China’s Export Import Bank (Exim Bank) to cover 85% of the project’s $1.2bn cost, and the work will be carried out, once again, by China Harbour Engineering.

The new port is being developed by a consortium that includes APM Terminals (APMT), Bolloré Africa Logistics and France’s Bouygues. When this team was picked in December 2013, it was not a great surprise: Bolloré and APMT already ran the existing container terminal at Abidjan.

The government of the Ivory Coast will pay for the preliminary marine and civil engineering, including dredging the Vridi channel, land reclamation and the building of the quay wall, at a cost of about $800m. The consortium will then spend around $600m to construct the container terminal it will operate for the following 21 years, creating, it is said, 54,000 direct and indirect jobs.

The terminal is scheduled to begin operations by early 2018, although it is thought to be running behind schedule.

Badagry, Nigeria: A brighter future

- Projected capacity: 2 million teu

- Draft: 15.5m (17m in later phases)

- To be completed: “Soft launch” set for early 2018

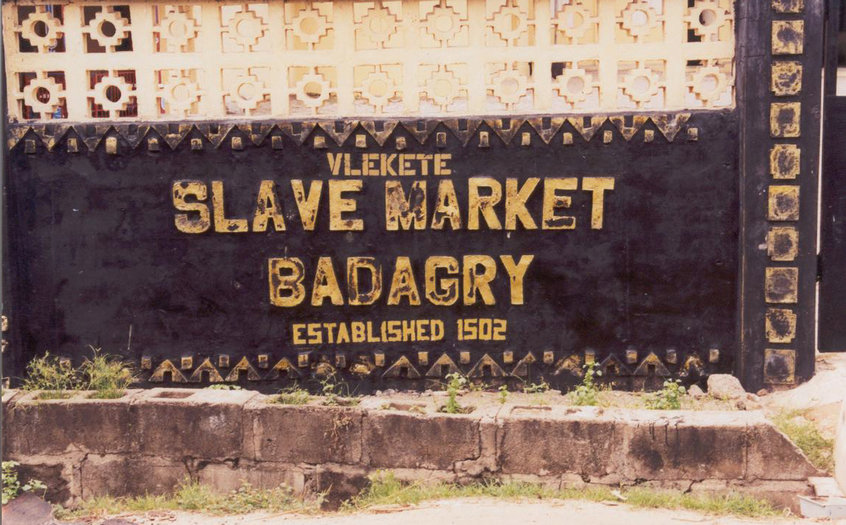

Badagry’s difficult past

It has a grim past as one of the earliest staging posts for the export of African slaves to Brazil, but the new port under construction at Badagry should herald a brighter future.

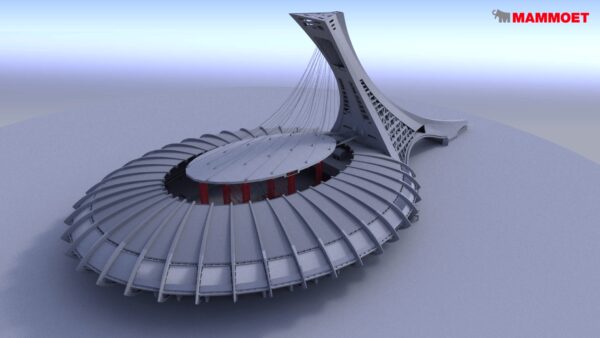

A render of the new port when complete

This $1.5bn development is Nigeria’s second strategy for relieving the pressure on Lagos. It was first proposed in 2012 by Apapa operator APMT as a greenfield site 55km west of the existing port. The proposal was accepted, and a 1.8m teu capacity project is now being developed by a consortium including APMT and TIL, with finance from Australian PPP specialist Macquarie Group.

The container terminal will begin with 775m of quays that can berth two Emden class 12,000 teu vessels. At full build-out, it will have 2.6km of quays and its bottom will be deepened from 15.5m to 17m to enable the port to accommodate ships of the EEE class, which have a loading of 18,000 teu, and which have never visited West Africa before.

In addition to the container ships, it will be able to deal with breakbulk carriers, tankers, roll-on, roll-off ships and general cargo vessels. As with Lekki, there are plans to site it in a free trade zone to encourage manufacturing companies to invest in factories.

Construction work began in January 2017, and the first ships are expected to berth in 2018.

When he first discussed the idea of Badagry, Peder Sondergaard, APMT’s chief executive for Africa, said the need for the installation was clear when you considered that Nigeria was projected to have a population of 250 million by 2045. However, the real problem, he said, was “infrastructure constraints” on “hinterland connectivity”. This is to be addressed with a 10-lane Lagos-Badagry expressway.

Port du Futur, Senegal: Dubai’s influence on Dakar

- Projected capacity: 1.6 million teu

- Draft: 15.2m

- To be completed: To be announced

Dakar container terminal (DP World)

Dubai-based port operator DP World took over Dakar, Senegal’s only deepwater port for container traffic, in 2007. In return for a 25-year concession, DP agreed to invest $450m to double the capacity of the existing Terminal à Conteneur, from 300,000 to 600,000 teu.

The second phase of the project is the construction of the 1 million teu Port du Futur, to be carried out in tandem with the development of the Dakar Integrated Special Economic Zone (DISEZ), a 6.5 square kilometre, $800m logistics hub and free-trade zone between the soon-to-be-begun terminal and the soon-to-be-completed Blaise Diagne airport. This will replacement Léopold Sédar Senghor, located in the centre of Dakar, which has a claim to be the worst sited airport in the world.

The additional port, which will located at Bargny, at the southeastern edge of Dakar, was announced by the Prime Minister Mahammed Boune Abdallah Dionne in December 2015. Altogether, these schemes will have a capital cost of around $1.25bn.

As always, it is easy to miss the significance of investment figures in relation to African economies. Although a $1.25bn project is large enough to arouse notice anywhere in the world, in Senegal, it is more than 8% of the country’s GDP: the equivalent of a $215bn project in the UK.

Kribi, Cameroon: Replacing the “worst port in Africa”

- Projected capacity: 1 million teu

- Draft: 16m

- Second phase to be completed: 2019

A difficult berth: the estuarine port of Douala (Creative Commons)

Perhaps the best news for shipping companies is that soon they won’t have to unload at Douala any more. This port at the mouth of the Wouri River has the reputation of being the worst in the whole of Africa.

The reason is that it has only 7m of draft, which means that feeders and general cargo ships with a deadweight above 15,000 tonnes have to anchor offshore and rely on barges to load and offload. Once in the port, a container takes an average of 21 days to be processed and, during busy periods, that can rise to more than a month.

This is a serious hardship for Cameroon’s mine owners, cocoa growers and timber merchants, who rely on the port for their economic livelihood, and it’s serious, too, for Chad and the Central African Republic, who have to thread their exports and imports through this needle’s eye, occasionally paying a $300-per-container surcharge to operator CMA CGM when backlogs build up.

The replacement is to be the port of Kribi, about 60km south of Douala. This will have a capacity of 1 million teu and will be able to handle vessels of up to 10,000 teu, making it a crucial element of the government’s Vision 2035, which aims to transform Cameroon into an industrialised middle-income nation by the target date.

The $585m first phase of Kribi involved the construction of a breakwater, a 362m container berth and a 308m general cargo berth. This was financed with a $500m loan from China’s Exim Bank and executed by the ubiquitous China Harbour Engineering.

There was then a pause for a bitterly fought bidding war to run the container terminal. In the end this was won by Bolloré, CMA CGM and China Harbour Engineering, seeing off ICTSI, APMT and French-owned operator Necotrans.

The second phase attracted another preferential loan from the Exim Bank – 2% interest with a seven year grace period – and work is under way on the 1-km-long quay, two hydrocarbon berths, two bulk cargo berths and two container berths. The project is expected to be complete in 42 months, after which a third phase will add 12 more berths at the northern part of the port. Meanwhile, a 510km railway to the country’s iron ore and bauxite mines is to be built by Portuguese contractor Mota-Engil (which also has the contract to build the breakbulk part of the port).

Comments

Comments are closed.

These new ports are long overdue yet very welcome in opening Africa up to world trade and accelerated wide ranging economic and social development so urgently needed! Thank you for such good news!