GCR’s four-part series on Africa’s new generation of modern megaports concludes with the Mediterranean, where port projects have become high-stakes bets with far-reaching consequences for their host nations

USS San Antonio transits through the Suez Canal, 2008 (US Navy photo/Creative Commons)

In August 2014, Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi ordered work to be begin on an $8.2bn project to upgrade the Suez Canal (pictured) by deepening the main channel, building a 35km parallel waterway and a further 37km of auxiliary channels.

The plan was to take advantage of an increase in world trade by increasing the number, size and speed of ships taking the short cut between Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean.

The business case for the project was that Egypt’s transit fees would increase from $5bn a year to more than $13bn by 2023, equivalent to about 3% of GDP. The development of a special economic zone would add another $55bn of assets to Egypt’s industrial base by 2030, with petrochemical production leading the way.

A certain amount of scepticism was expressed in the business press about those figures: one shipping broker told Bloomberg the expansion was “a bit of a surprise” as no shipping companies had requested an expansion in capacity.

Ahmed Kamaly, an economist with the American University in Cairo, told Reuters that traffic projections were based on “wishful thinking” rather than conventional feasibility studies. The purpose of the scheme, he said, was political rather than economic: to unite the Egyptian people around a source of national pride, much as Ethiopia had done with its Grand Renaissance Dam.

And, as with the dam, it was financed by popular contributions: in this case, special investment certificates, which were fully subscribed within eight days of release. A national holiday was announced on the day the parallel waterway opened.

Political economy

The Suez 2.0 plan made sense as a way of strengthening the position of al-Sisi’s government, however it came with certain risks. It’s all very well to associate yourself with a prestige project that succeeds, but failure can be hard to live down. So far, things have not gone well: the hope was that the average number of ships using the canal would increase from 47 a day to about 97.

Figures for December 2016 show that only 49 were passing through, and to sustain that level of traffic the Suez Canal Authority has had to offer discounts to shippers of between 45% and 65%, leading to a 5% year-on-year fall in revenue in November 2016. It was recently announced that these will be in place until the end of June.

The discounts have proved necessary because major shipping lines have been taking advantage of lower fuel prices to send their cargoes round Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. And many ships sailing from Chinese ports have been opting to reach the east coast of America by crossing the Pacific and passing through the expanded Panama Canal rather than taking the shorter route across the Indian Ocean.

In the years to come, world trade is likely to grow and the price of fuel will probably rise, meaning the decision to upgrade the canal could eventually pay off, but this may be a long wait. Meanwhile, Egypt is facing short-term economic challenges that the project may have actually exacerbated.Â

Two kinds of ship … (Creative Commons)

A new Antwerp

At the other end of the Mediterranean is another remarkable example of a government using civil engineering as a lever to move an entire economy, in this case that of the north Moroccan region, which contains most of the country’s industry and population.

The port in question is the Tanger-Mediterranean terminal, directly opposite Gibraltar, which opened for business in July 2007 with a design capacity of 2.8 million teu. By 2014 the volume of containers had already reached 3 million, putting it equal to Africa’s biggest, busiest and best facility at Durban in South Africa. Growth fell back 3% in 2015 – unsurprisingly, given the 10% fall in global merchandise trade in that year – but it was clear to the government of Morocco and the Tanger Med Port Authority that the longer-term prospects justified an expansion to as many as 9 million teu. This is now under way, and when it is complete, it will mean that a port that didn’t exist 10 years ago has become the equal of Antwerp.

The growth potential of a container terminal lies in its location relative to trade flows. Here Tanger-Med is at even more of an advantage than the Suez terminals, being 10 days sailing from the New York, three from Rotterdam and 20 from Shanghai. What’s more, it is on the “line of zero deviation” for ships on the east-west trade run through Gibraltar, which includes 20% of the world’s maritime traffic. In other words, ships can call there without diverting from their course, and unload boxes for transhipment by road, rail or feeder ship. This is set fair to make Tanger-Med the largest port in the Mediterranean. And together with its state-of-the-art equipment, low charges and four special economic zones, it looks likely to become a shining example of infrastructure-led development for the whole of Africa.

As is usually the case with shining examples, surrounding countries are hoping to follow suit. The following is a tour around the southern shores of the Mediterranean, where some remarkable projects are being put into practice.

Work is well advanced on Morocco’s megaport (Bouygues)

Morocco is the site of the most ambitious terminal expansion plan anywhere in Africa: the €825m Tanger-Med II. This will add a separate, larger, harbour to the western edge of Tanger-Med I, as well as two container terminals with the capacity to handle 5 million teu. There is scope for additional expansions after the first phase is complete in 2019, which would bring the combined capacity of the ports up to 9 million teu.

The new port will be run by local company Marsa Maroc and APM Terminals (APMT), a company based in the Netherlands but owned by Danish shipper Maersk. The work is being carried out on a design-and-build basis by the same consortium that built Med I, led by Bouygues Travaux Publics and including Besix of Belgium, Saipem of Italy and Somagec and Bymaro of Morocco.

The work includes the construction of a 4.4km of breakwaters, a 1.6km quay for terminal 3 and a 1.2km quay for terminal 4.

Tanger-Med is ideally placed to provide unloading points for the 100,000 ships a year that pass through the Straits of Gibraltar, and to gain the greatest profit from this flow it has installed the specialised cranage required to reach into the latest Ultra Large Container Ships, which cram as many as 20,000 containers into their 59m beam.

Staying with the subject of loading and unloading, another feature that Tanger-Med II will offer to shippers is the use of the latest 52m-high ship-to-shore remote controlled cranes: 12 have been ordered from Shanghai’s ZPMC, and will be delivered at the end of this year. They will be supplemented by 32 automated rail-mounted gantry cranes from Austrian engineer Künz. The aim of this state-of-the-art equipment is to offer the fastest, most cost-effective service, which is important in Tanger-Med’s battle with Algeciras (4.5 million teu), on the other side of the straits, and will become even more so in the coming years as rival ports go into business along the North African coast.

Tanger-Med is also a demonstration of the ability of container terminals to form the nucleus of large industrial complexes. The four export-orientated free trade zones around this one have experienced a rapid influx of investment, particularly in the automotive, aeronautics and textile sectors: one anchor tenant is Renault, which is building the largest car factory in Africa, with a capacity to produce 340,000 vehicles a year, and in March 2017 Chinese aerospace company Haite announced plans to build a $10bn industrial and technology city.

Altogether, the economic zones in place now provide manufacturing sites for 700 companies over 1,200ha, and generate revenue of about €5bn a year.

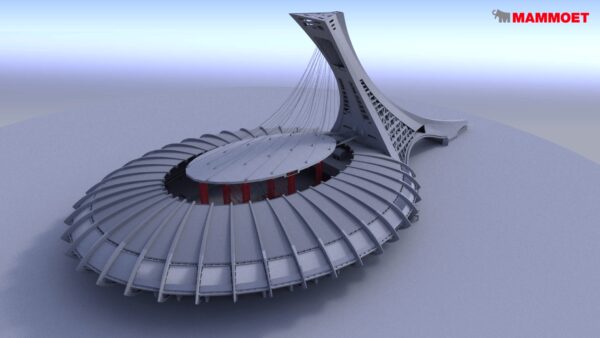

Following suit: El Hamdania

- Capacity: 6.5 million teu

- Draft: 20m

- To be completed: 2024

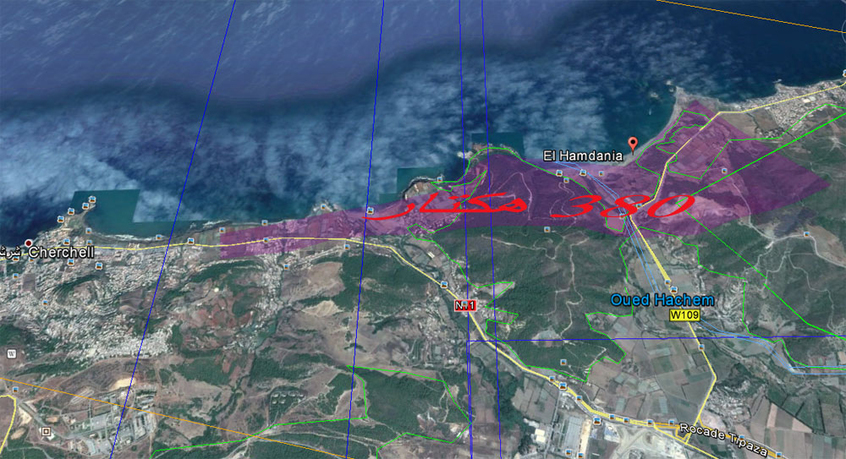

The 380ha set aside for the port (Port de Cherchell/Google Earth)

Algeria is one of a number of petro-dependent nations around the world that are trying to develop healthier mixed economies.

Part of this process involves building container ports to go alongside the LNG and oil terminal. At present, Algeria moves around 10.5 million tonnes through the ports of Algiers and Ténès; the aim is to increase this to 35 million tonnes by 2050.

This will be made possible by what Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal calls “the biggest project since independence”: the new port of El Hamdania, near the ancient Phoenician town of Cherchell, 55 miles west of Algiers.

A $3.5bn deal to build the port was signed in January last year by Algeria’s Transport Ministry with a consortium led by China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) and China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC). They will take a 49% stake in the completed asset, with Algerian Port Authority taking the rest. Some $900m of the financing will come from a 20-year soft loan from the African Development Bank; much of the rest will be loaned by a consortium of Chinese banks, whose identities have not been made public.

The plan is to build a facility somewhat larger than New York or Bremerhaven: 23 docks capable of processing 6.5 million teu and 26 million tons of goods per year. The first phase of the project is expected to be completed within seven years, with subsequent stages brought in over the following four years.

Work began on site in March 2017 and the first berths are scheduled for completion in 2021.

Shaky start: the Suez Canal Container Terminal

- Capacity: 5.4 million teu

- Depth: 17m

- Opening: Expansion completed in 2016

The SCCT’s state-of-the-art cranes in action

The Suez Canal Container Terminal (SCCT) at Port Said East was opened for business in 2004 as the main transhipment hub of the eastern Mediterranean. As it was situated at the northern entrance of the Suez Canal, it was well placed to take advantage of the flow of ships to and from the Indian and Atlantic oceans, and it quickly became the largest container port on the North African coast, dealing with 3.5 million teu. Since then it has undergone around $800m of additional upgrades to increase its capacity to 5.4 million teu.

The SCCT is being operated by a joint venture between AMPT (55%) and Hong Kong shipper Cosco Pacific (20%) and, as with AMPT’s Tanger-Med, investment is being aimed at installing the latest generation of 52m ship-to-shore cranes to accommodate the immense carriers that shipping companies believe to be essential to scraping a profit. The $42m investment included one vital item: the excavation of a dedicated 9.5km access channel, which was completed in February 2016. This means that ships no longer had to access the port through the canal, which often involved a six-to-eight hour wait for a slot to become available.

Jeff De Best, APMT’s chief operating officer, made a speech at the opening ceremony of the upgraded port on 6 August 2015.

In it he expressed the wish that the expanded Suez Canal would “play an even greater role as a gateway of global trade”.

Unfortunately for the operators and the wider Egyptian economy, traffic using the port has fallen by nearly a quarter between 2015 and 2016. And, according to Cosco, throughput fell a further 21% in the first six months of 2016 – 23% in June alone.

The port in a storm: Enfidha, Tunisia

- Capacity: 5 million teu

- Draft: 17m

- To be completed: September 2019

A rendering of the completed port (Port Enfidha)

Tunisia has two container terminals at present, the Port of Rades at the capital Tunis, near the top of the country’s north-south aligned coast, and Sfax further to the south. If all goes to plan – and it is a big “if” – these two will shortly be dwarfed by a €1.3bn deepwater megaport located roughly halfway between them in the Gulf of Hammamet, near the small town of Enfidha.

As with Algeria and Morocco, the port is seen as a way of making use of Tunisia’s position on the fringe of the vast EU market to develop low-cost manufacturing and assembly industries, and as with Egypt the aim is to defuse social tensions created by the 30% unemployment rate among those under 25. The Arab Spring, which began in Tunisia in December 2010, has left the country with a democratic system, but no stable government: there have been seven prime ministers in the past six years.

Plans for a container port at Enfidha were drawn up before the 2008 crash, and then delayed by waves of economic and political turmoil. Now the government of Youssef Chahed has made the project one of the centrepieces of its 2016-20 five-year plan. A target date of September 2019 has been set for the opening of the first phase – a timetable that will require the government to hustle through the preconstruction stages at a rate of knots.

The plan is to set aside a huge area for the port: 1,000ha. There will be no fewer than 5km of quays, of which 3.6km will be dedicated to container traffic and 1.4km for storage. The cranage will aim to accommodate ships carrying up to 18,000 boxes. Alongside the port will be a 3,000ha logistic zone, and the hope is that the whole project will provide direct employment for as many as 20,000 people.

The difficulty that Tunisia faces in realising this project is attracting foreign investment. Altogether, the five-year plan calls for $60bn to be injected into industries such as aerospace, automotive and tourism, but foreign companies, and foreign visitors, see the country as risky, both in terms of its political stability and their physical safety. As a result of this, some 500 foreign companies have actually left the country since 2011. The government has warned that instability may intensify if Europe continues to disinvest.

Mohamed Fadhel Abdelkefi, the minister of development, told the Financial Times last October that the West was in danger of jeopardising one of the few gains of the Arab Spring. “As the only Arab and Muslim country to set up a full democracy, we can say Islam and democracy are not in opposition. If you solve the economic situation of Tunisia, you would find tomorrow an example to give the Muslim world.”

Read more reports in this series:

Africa’s ports revolution: setting the scene for economic take-off