Africa’s infrastructure deficit is painfully obvious to anyone trying to traverse the continent, but for those unable to give it a go, the gap is just as glaring on paper.

Here are some interesting stats.

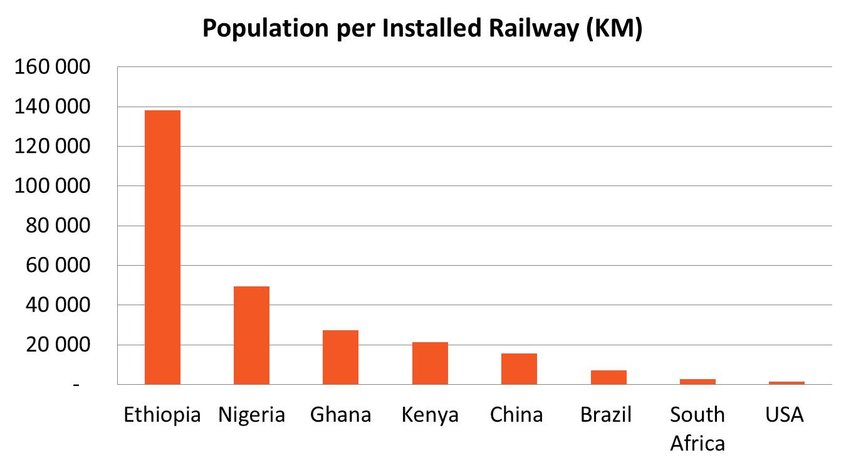

China has a kilometre of rail for every 15,700 people. Another developing country, Brazil, can offer more than twice that capacity: there, 7,100 people must share every km of rail.

In Ethiopia, a km of rail must be divided up among 140,000 souls.

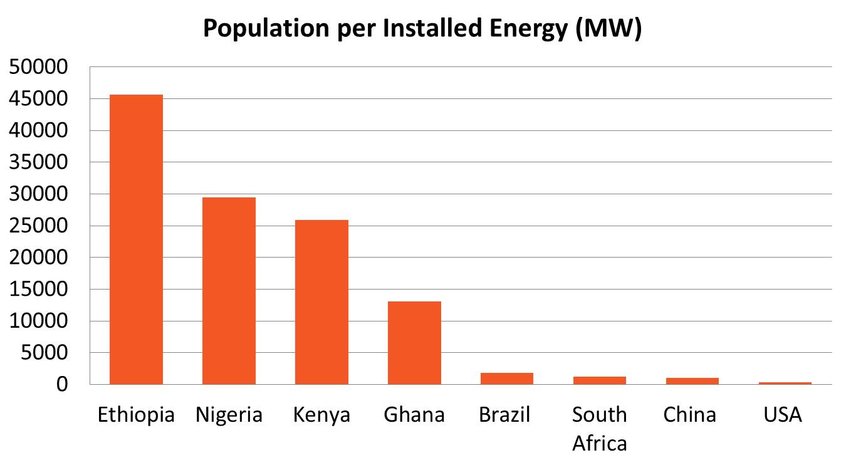

The gap is equally stark in terms of electricity. In China there are 1,080 people per 1MW of installed energy capacity, and in Brazil there are 1,780 people per MW.

In Ethiopia the figure is 45,000.

The infrastructure gap is holding Africa back. Infrastructure is a catalyst for economic growth but, to attract large foreign investors, countries need to lower their cost of doing business. High transport and energy costs drive up the prices of goods and services

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook; CIA Factbook; RisCura Analysis

Why help others?

Given the significant capital outlay and political risk associated with infrastructure projects, governments are the principal agents of change to improve the situation.Â

Some countries are realising the benefits of collaborating with their neighbours to plan and execute infrastructure projects, and the effects of this are encouraging to see.

For a number of reasons, however, others are not.Â

One reason is political. African voters demand more from their leaders as they see how people live on other continents. This can incentivise leaders to maximise their own political mileage by implementing infrastructure projects independently and taking all the credit.Â

Another reason is that the scale of the projects makes it tempting for state officials to profit from the transactions, especially if they retain full control.Â

Countries in Africa also compete against each other, so aiding neighbours by reducing the cost of doing business at first glance appears counterproductive. Â

East Africa collaborates

But not everybody thinks like this.

The East African region, which includes Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan, has been leading the charge in collaborative infrastructure planning and execution.

One of the benefits of a joint approach is access to bigger markets.

African countries that work together will actually give themselves a head start by sharing risk and funding requirements–

Countries like Nigeria and Ethiopia have 174 and 94 million people respectively, while smaller countries like Rwanda and Togo have 11 and 7 million.Â

To compete, smaller nations such as Rwanda have teamed up with bigger neighbours like Kenya and Uganda, harmonising immigration and infrastructure plans in order to market themselves to investors as integrated economic hubs.Â

Power sharing

In addition to market size, the cost of electricity profoundly affects East Africa’s attractiveness as a manufacturing base.Â

Competitors from outside the region such as Egypt and South Africa charge users on average US 8 cents and US 9.10 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) respectively. East African regional powerhouse Kenya on average charges industrial users USD 15 cents per kWh.

To lower electricity costs, the region is investing in cross border transmission lines. This allows producer countries to sell excess power to neighbours, and gives non-producers access to cheaper power.

Take Kenya and Ethiopia. The expected completion of the Kenya-Ethiopia electricity line in 2018 will see Ethiopia able to transfer 2,000 MW of power. This would allow Kenya to reduce its cost of power by sourcing the cheapest form of renewable power, hydroelectric power.

Big schemes cost too much for most African states to pursue by themselves–

Ethiopia on the other hand will generate much needed foreign exchange and a market for the excess power that will be generated from the Gibe III hydroelectric project, with an installed capacity of 1,870 MW. A similar transmission project to the Kenya-Ethiopia transmission line is planned from Kenya to Rwanda crossing Uganda.

With the capacity to generate 45,000 MW of hydroelectric power, Ethiopia is capable of supplying the entire East Africa Region, which has a total installed capacity of 3,520 MW. The power sold is expected to cost between 3 and 10 US cents per kWh.Â

If achieved, this will make the whole region competitive versus other low cost energy producers on the continent. Â

Sharing the cost

Another benefit of joint infrastructure projects is the ability to mobilise funds.Â

Big schemes cost too much for most African states to pursue by themselves. The high cost of commercial loans forces them to seek concessionary loans from either development institutions or developed nations, and their chances of success are higher if nations band together and lobby as a collective unit.Â

The Kenya-Ethiopia electricity transmission line is estimated to cost $1.2bn. By banding together, Kenya and Ethiopia were able to secure funding from the African Development Bank.

Another example is rail. Think of the ambitious project to lay a standard gauge railway from the Kenyan port city of Mombasa to the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, and on to Kampala in Uganda, and then down to Kigali in Rwanda.Â

It is projected to cost $11bn, but is widely expected to exceed that figure.Â

Individually, the countries need rail, but making the scheme regional in scope attracts big investors – in this case, the Chinese government. Â

It may seem counter-intuitive to collaborate with competitors, but African countries that work together will actually give themselves a head start by sharing risk and funding requirements.

For their part, investors are keenly following such developments as they prepare to base their operations in environments that make them more competitive.

- Brian Maina is a private equity analyst at RisCura

Main photograph: Ethiopian president Mulatu Teshome, left, welcomes the president of Uganda, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on 26 December 2014 (Minasse Wondimu Hailu/Anadolu Agency/Getty)

Comments

Comments are closed.

I hope this action is an incentive for all African countries to join forces for their bettermen