Beirut architect MDDM’s concept of an “invisible landmark” has won an international competition to add a Knowledge Innovation Centre to one of the 20th-century’s most famous pieces of unfinished architecture, the Rashid Karami International Exhibition Centre in the Lebanese port of Tripoli.

The centre was designed in the early 1960s by Oscar Niemeyer in the same neo-futurist style he made famous in Brasilia the previous decade. It was to have been one of the largest exhibition spaces in the world, but construction was brought to a halt by the 1975 Lebanese Civil War.

After the war ended in 1990, the project consisted of 15 low-rise structures that had been wholly or partly built, including a “grand canopy” – the dominant element of the site – as well as a heliport, space museum, rotating restaurant, indoor and outdoor theatres and communal housing. These were then allowed to decay to the point where the government began to talk about bulldozing them to make room for a theme park.

Niemeyer’s Lebanese Pavilion on the Rashid Karami site (Dreamstime)

The prospects for Rashid Karami have recently improved, however, thanks to the creation of the Tripoli Special Economic Zone, a programme with an aspirational budget of $300m that aims to boost the city’s economy by building a high-technology hub on an undeveloped area of the 100ha site. This plan has been helped by Unesco’s decision to add it to the list of sites being considered for world heritage status – if that goes ahead, Niemeyer’s structures will almost certainly be preserved.

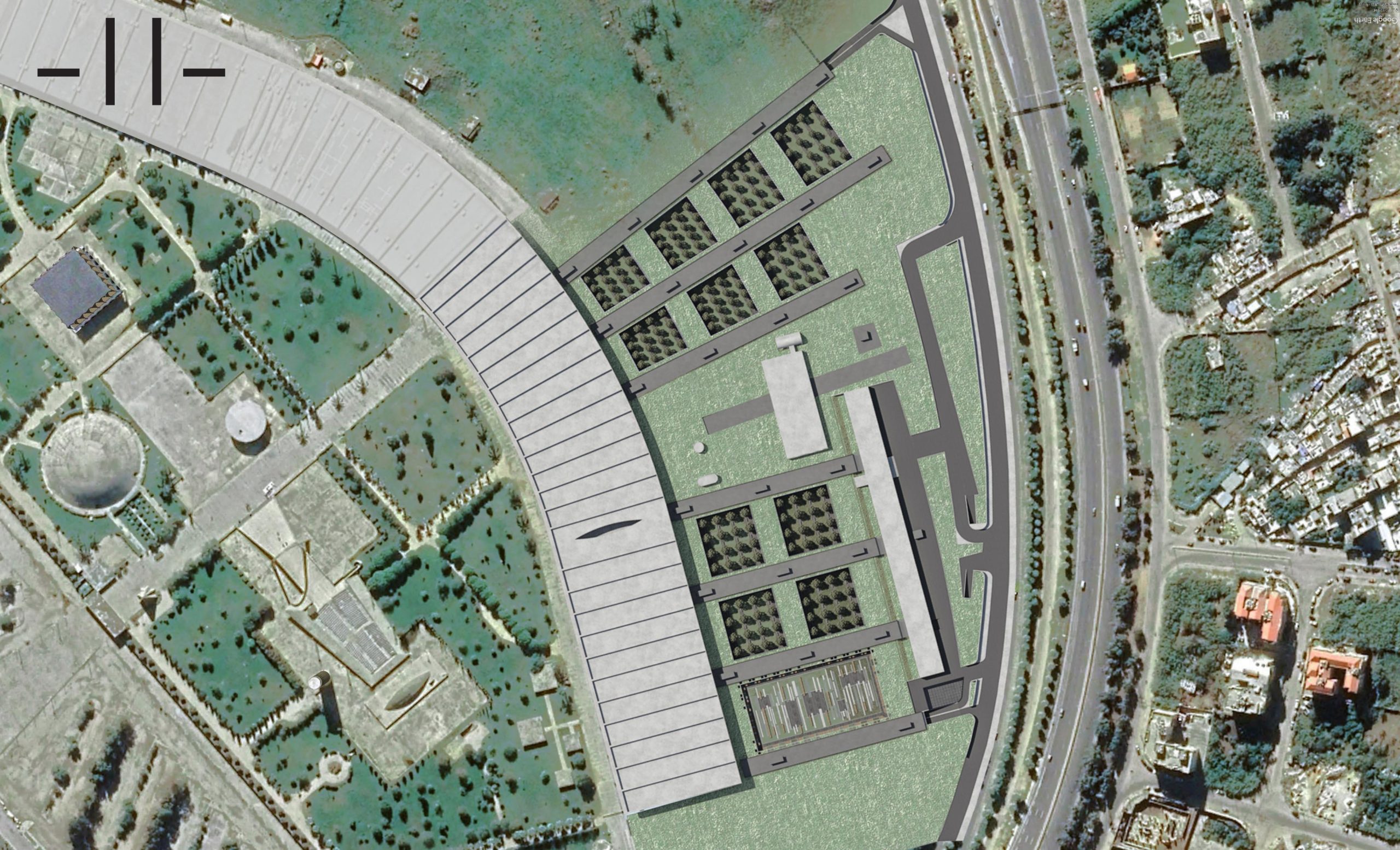

The Knowledge Innovation Centre is to be a 60,000 sq m business and technology park, with some residential elements, and it to fit onto an area of 75,000 sq m.

The design brief posed two unusual challenge for entrants.

Firstly, the buildings had somehow to “blend in” with Niemeyer’s surreal modernism – any failure here might jeopardise the Unesco listing. Secondly, it would have to develop a “flexible phasing strategy” – meaning that work could be paced according to the availability of finance, and the project could make money as soon as possible.

Imad Aoun, MDDM’s co-founder, says the problem boiled down to fitting “a highly functional building into a highly conceptual site”.

The planted courtyards are 55m-long squares (Photo courtesy of MDDM)

He and co-founder Nadim Younes considered taking either a low-rise or a high-rise approach. The former was rejected on the grounds that it would “unbalance” the site by taking up too much ground and too much of the view of Niemeyer’s structures.

The high-rise option, by contrast, was more attractive. For one thing, it would leave the site “aeriated”, it could be designed to complement Niemeyer’s style, and as Aoun says candidly, “a 60-storey tower would definitely satisfy our need for a star project”. However, this approach had to be rejected as well, since there was no way of designing a would-be icon in a way that would respect the project’s economic frailty. Â

Fortunately, there was a third solution that solved all the problems. This was to put 80% of the centre underground, thereby leaving the field to Niemeyer, and by making it modular so the work could be stopped and started with the minimum of cost and fuss.

Aoun says that a number of other 100 entrants to the competition also hit on this plan, but MDDM’s concept won because it dealt best with two problems: the gloomy feel of being underground and the need to allow the start-ups that leased space in the hub to display their presence.

The above ground elements were aligned with Niemeyer’s “grand canopy” (Photo courtesy of MDDM)

The first problem was met by creating 11 sunken and landscaped courtyards that would allow you to go underground “without the feeling of being underground”, the second by adding large company logos to the above ground areas. There was also the need not to entirely ignore the presence of Niemeyer, so MDDM aligned the courtyards and the strips of building between them with the ridges of the grand canopy.

The competition jury gave MDDM the prize on the grounds of its “clear strategy and its rigorous approach”, and noted that the linear structures recalled some of Niemeyer’s early designs, and resonating with the rhythm of the grand canopy.

MDDM – not to be confused with the Beijing architect MDDM Studio – is now working on an extension of the Casino du Liban – the only casino in the Arabian peninsula.

Top image: The idea of courtyards and signed dispelled the “underground effect” and allowed companies to announce their presence (Photo courtesy of MDDM)